Archaeologist as Technician

How Technology Has and Continues to Shape Visions of the Maya Archaeologist

The archaeologist has often appeared in popular and academic imaginations as exceptionally equipped to see into the past.

Whether as a scientist, scholar, adventurer or something in between, the archaeologist is seen as able to reconstruct the past via artifacts and landscapes that are thought to be embedded with hidden histories that they are particularly suited to analyze.

This capacity for deep historical sight is regularly portrayed as a consequence of the archaeologist’s unique technical literacy or their ability to use precise, cutting-edge technologies to glean otherwise hidden information from their objects of study.

(Pictured Left Archaeologist using total station to take field measurement: Photo by Irma Havlicek)

As such, be it in popular culture or more obscure corners of academia, the archaeologist as technician has remained a popular image used both professionally and popularly to signal the unique qualifications of the archaeologist and the objectivity of their historical interpretations since its inception.

This shorthand page explores the origins and persistence of the archaeologist as technician through considerations of technologies of seeing employed in Maya archaeological history: ranging from sketches in the mid-19th century to present advances in canopy penetrating remote sensing technologies like LiDAR.

Ruins of Tikal: Shutterstock

Camera Lucida

Early Imaging in Maya Studies

Camera Lucida and Early Imaging

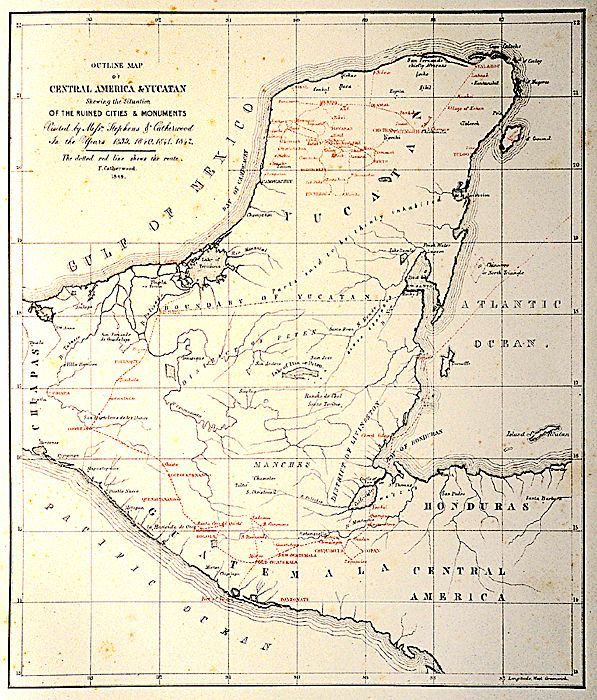

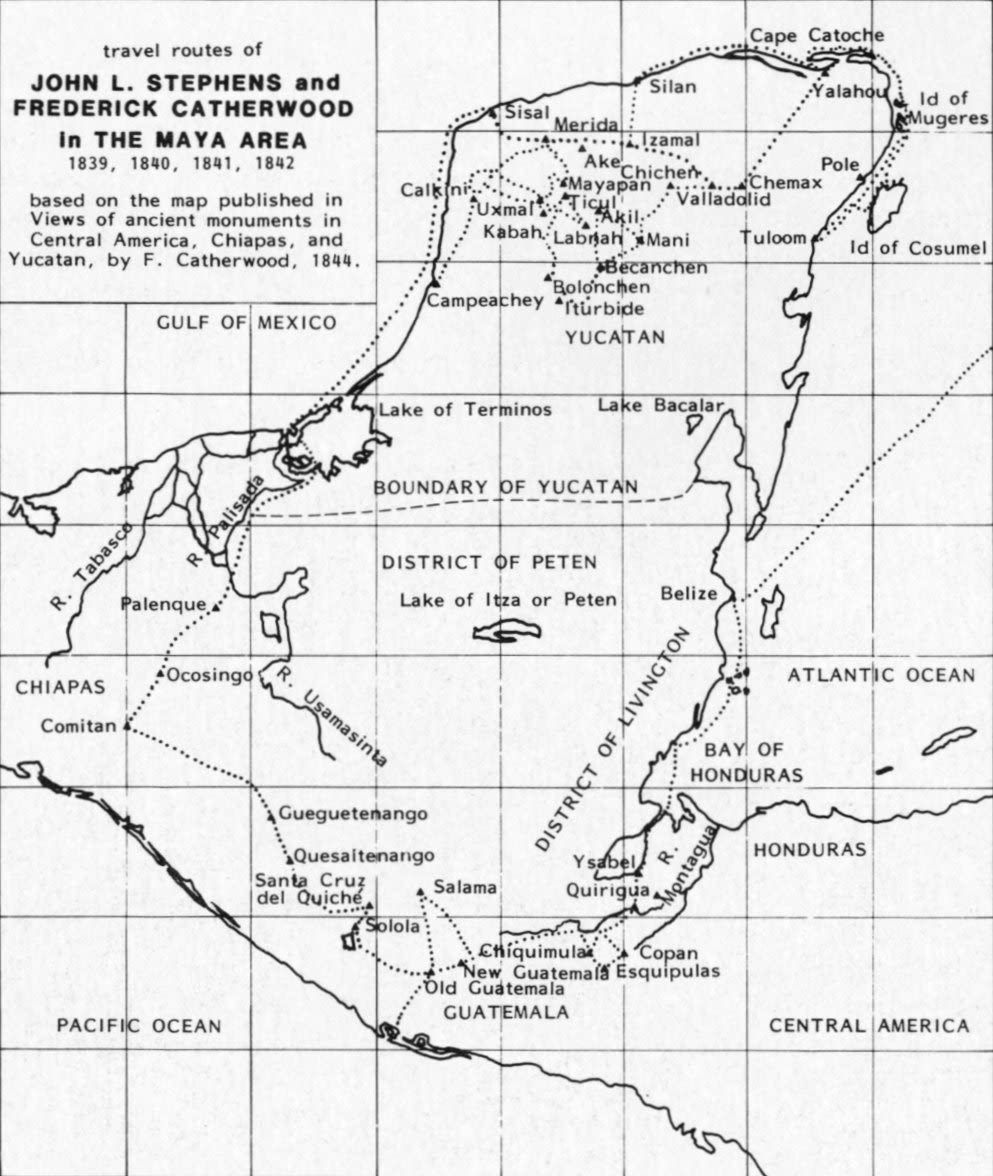

In the middle of the 19th century American lawyer John Lloyd Stephens and British architect Fredrick Catherwood traveled through Central-America in search of Maya ruins. As they went, they took extensive notes which Stephens would later turn into his discovery narratives: the Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan (1841) and Incidents of Travel in Yucatan (1843) named after the sites of their travels.

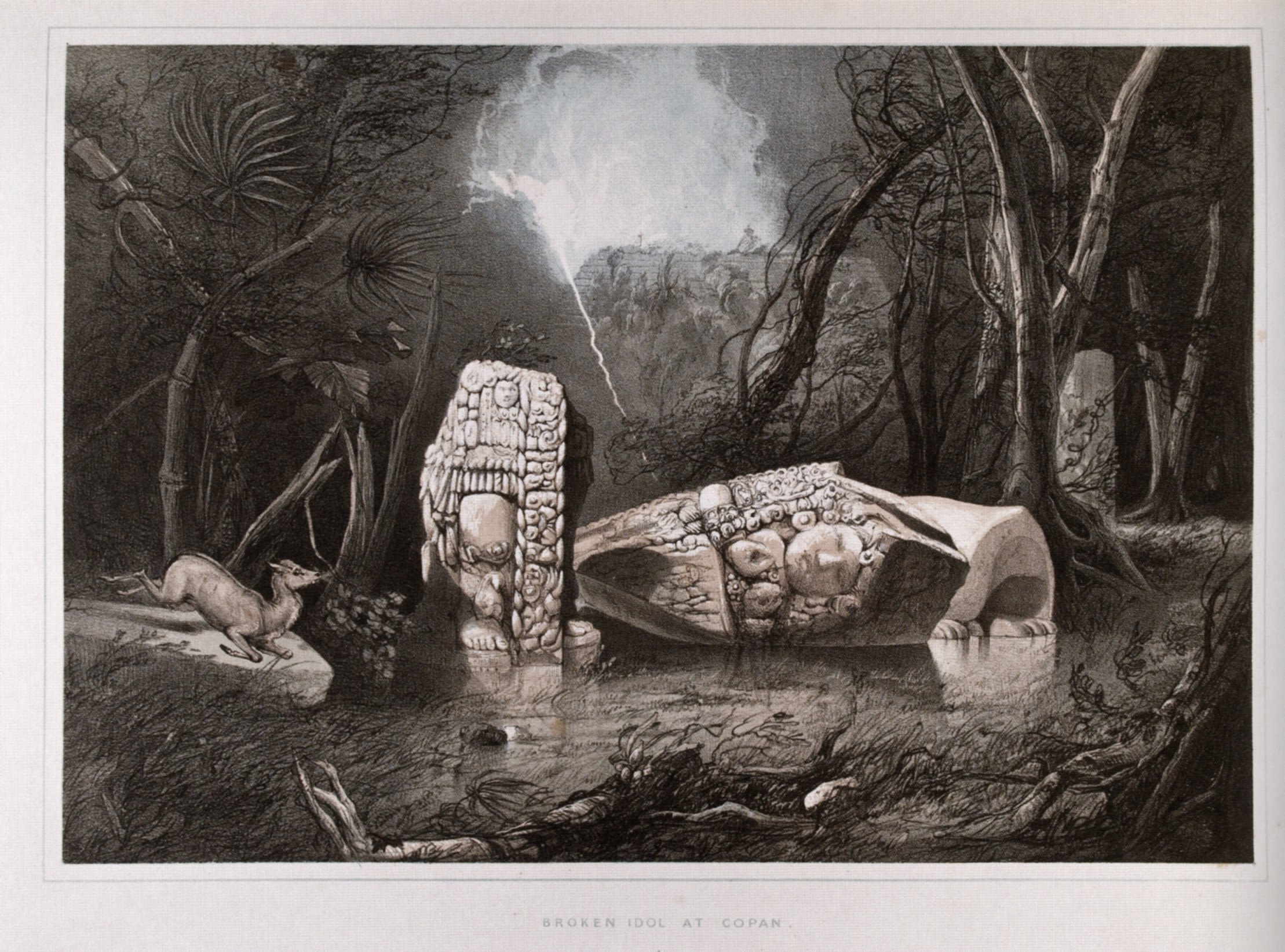

In addition to being two of the first popular accounts of Central American ruins, the works were also catalogs of images including over 200 engravings made from the sketches Catherwood took throughout their travels. (Catherwood's are this section's background images as seen on right)

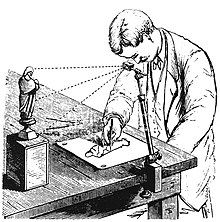

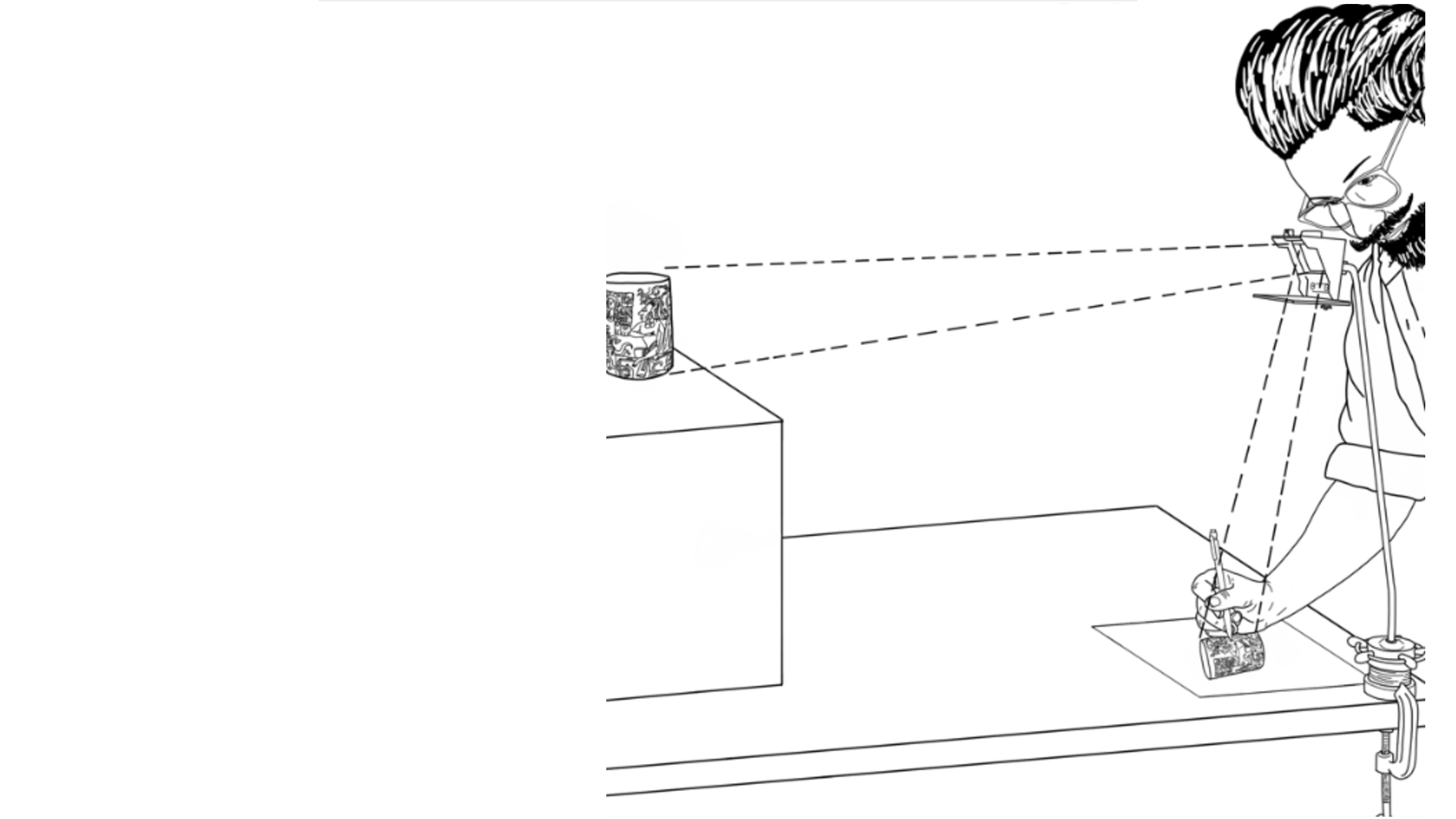

While many of these engravings were made from freehand sketches, vitally important to producing such a large body of drawings was Catherwood’s use of the Camera Lucida, a device that used a prism to reflect the landscape onto a traceable surface. Given adequate light, the camera lucida allowed the user to trace over what was in front of them and allowed them to pay particular attention to perspective and spatial depth of the landscape.

As a technology, the most important quality of the camera lucida according to Stephens was its capacity to enhance the precision of drawings/engravings to the point of “truth” (137 in Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan (1841) ).

While Stephens did not play down the fact that Catherwood’s steady and artistic hand was necessary for the technology to work out in the field, the camera lucida was highlighted as something that reduced the margins of interpretation to such an extent that it was possible to access what was objectively or ‘truly’ out there. Rather than provide the context of monuments and stelae via robust or lengthy descriptions, the reproductions produced with the camera lucida allowed “the monuments speak for themselves” (137).

Nearly two centuries later, a similar interpretation of Catherwood’s competence as a technician and his unique early objective employment of the camera lucida is still noted, with claims that while “Romantic Era influences are apparent in his use of light and colour, and the styling of plants and animals… his renderings of Indigenous designs is always precise.” Though supposedly superfluous elements of his drawings like plants and animals are seen here as artistically rendered in accordance with certain romantic notions of the past, the technical employment of the camera lucida ultimately rescues Catherwood’s engravings from the realm of biased interpretation and secures them as things embedded with an inherent degree of objective historic value.

Right, Illustration of Catherwood using camera lucida: Image by Carmen Kors (2018)

Here, it is important to more critically interrogate the idea that the romantic influences of Stephens and Catherwood’s work were of a fundamentally different sort than the technological influences of the camera lucida. In the same account in which Stephen’s outlined the capacity of the camera lucida to reveal the “truth” or let the “monuments speak for themselves” he also laments the copying a certain “idol” that: “As we feared, the designs were so intricate and complicated, the subjects so entirely new and unintelligible, that he had great difficulty in drawing. [Catherwood] had made several attempts, both with the camera lucida and without, but failed to satisfy himself or even me, who was less severe in criticism. The 'idol' seemed to defy his art" (120 Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan (1841)

Even with the camera lucida some engravings and designs still eluded representation, even with the camera lucida. Thus, it was not the fact that the camera lucida indiscriminately captured what was ‘out there’ more so than it facilitated or enhanced documenting things that the user was familiar with or with which they had an established interpretive framework from which to view them. This is not to say Catherwood was not using his art to explore a subject that was previously unknown in his culture and doing nothing more than casting a preconceived romantic vision onto the ruins; instead, it is to say that he was likely keenly aware of his things such as his audience’s expectations of what men like Stephens and himself might find and this inevitably shaped what got represented. As such, it is important to keep in mind that what may seem like superfluous elements of Catherwood’s engravings today are things that actually give us great insight into the framework from which Stephens and Catherwood considered their objects of study: primarily the lens of the technically literate scholarly gentlemen that they imagined themselves to be.

When contextualized alongside the narrative accounts which Catherwood’s engravings are set within, we find that the camera lucida is just one of many tools that established the men as people fit to make discoveries according to the logics of their social standing or class. While the camera lucida was presented as unique in its capacity for objective image making, it was also situated within a milieu of other social and political tools such as letters of credentials from Central American military elites, trunks of medicines to be distributed to locales, and masculine descriptions of navigating the dense rainforest. That Stephens centered such things so prominently in his narrative to establish the social standing of himself and Catherwood demonstrates the wide range of things that went into marking one as fit to make 'objective' judgments at this time (123).

Discovery is the primary theme of Stephens’ writing and the interpretation of the overgrown jungle via a mix of technical, social, and political tools was what ultimately enabled the two to establish themselves as erudite and adventurous gentlemen of their time, capable of revealing a truth that was lost. From its origin then, the archaeologist as technician emerged as an identity bound up with several competing and reaffirming ideals and tools that established the credibility and objectivity of people who had access to them.

Next Page: Map of their travels from "Views of Ancient Monuments" (1844)

Aerial Photography & Flight

The Technician in the Interwar Period

Image, Maya ruins at Chichén Itzá, Yucatan, Mexico: Yale University Library

The Technician in Flight

With this historic perspective in mind we can turn to another major development in archaeological technologies of seeing and its particular effect on making the Maya archaeologist as technician: aerial photography.

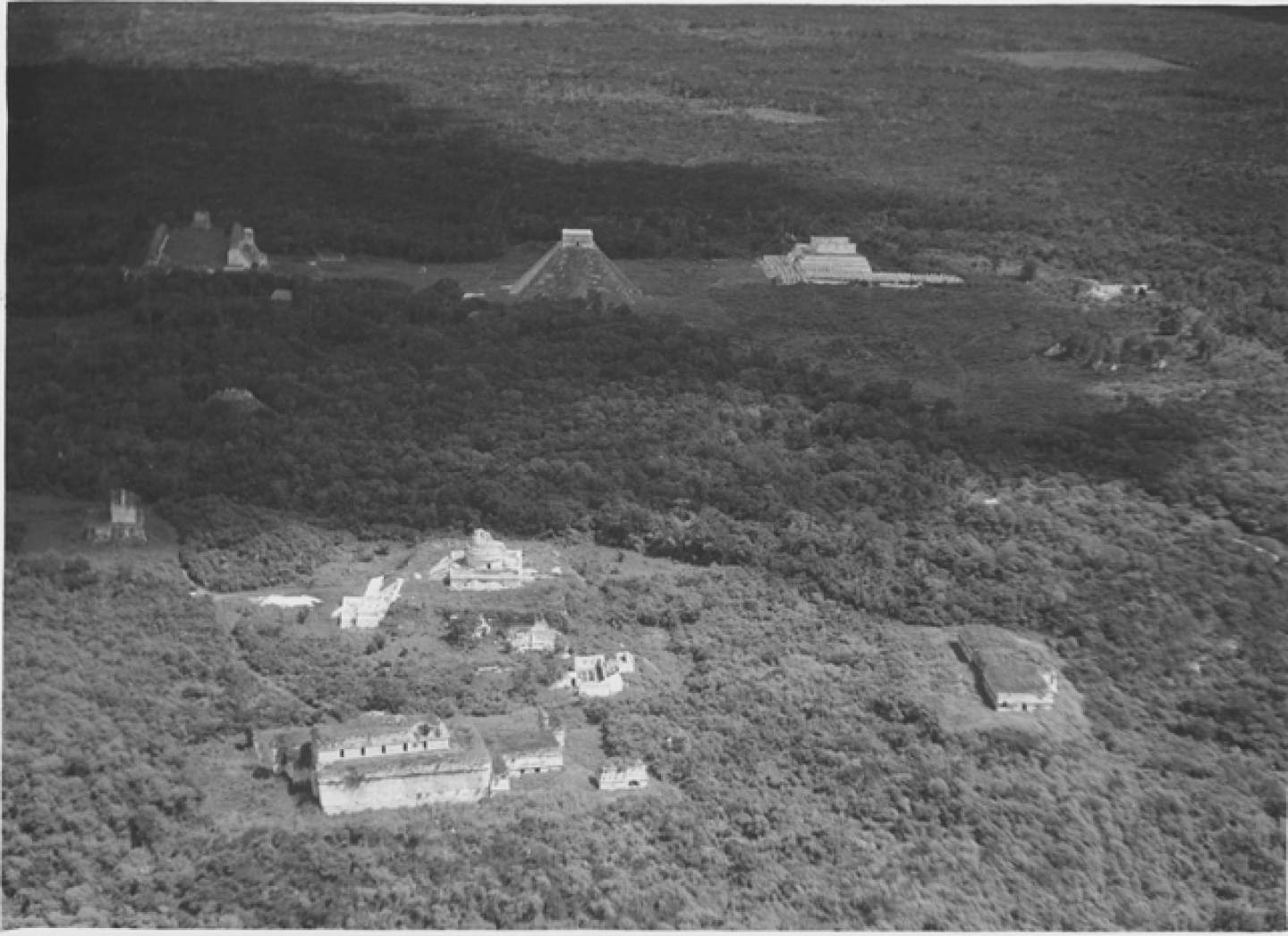

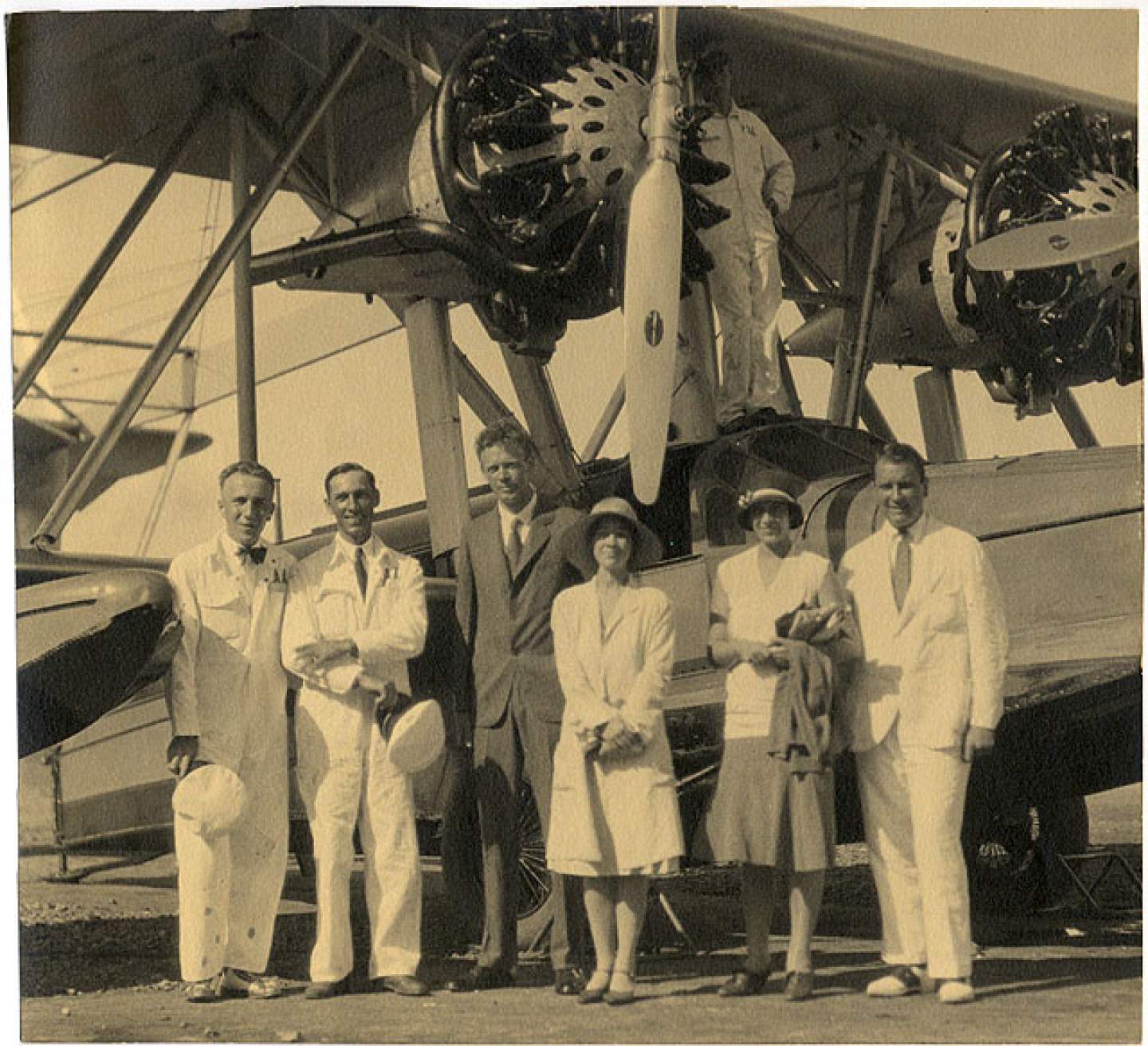

The first aerial photographs of Maya sites were done by Anne and Charles Lindbergh in 1929. The couple got involved in archaeological photography after Charles had spotted unusual mounds and other similar features while flying an inaugural route for the Pan American airmail service from Havana to Panama (below Front and back cover of Pan Am’s first timetable via James Patrick Baldwin).

When he returned to Washington D.C., Charles got in contact with the Carnegie Institute of Washington (CIW) which at the time had several of the largest active archaeological projects in the American Southwest and Central America, including many Maya sites.

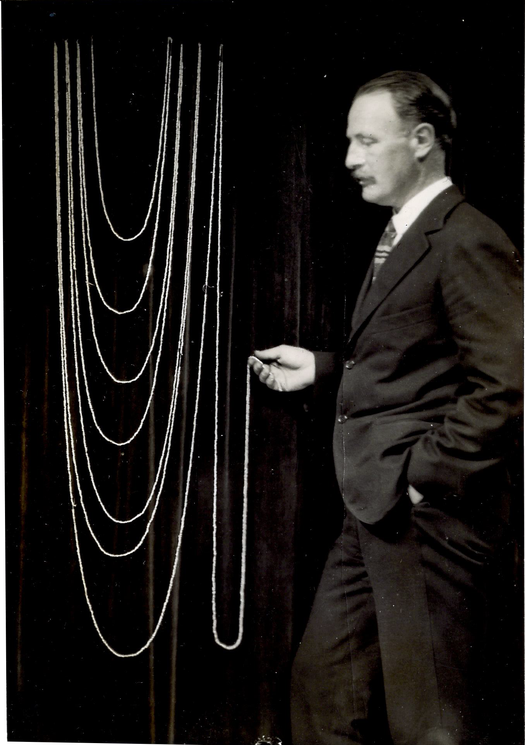

Charles was referred to archaeologist Alfred V. Kidder, a then widely accomplished archaeologist who succeeded Sylvanus Morley in overseeing the massive Uaxactun project. Kidder would go on to ask Charles if he would be willing to photograph any interesting features on a flight that passed through the American Southwest later that the summer since Kidder also worked on Puebloan sites (Kidder with with beads from Pecos Pueblo, June 8, 1929 via Harvard Peabody Institute)

After taking over 100 photos on this flight he and Anne were asked to photograph Maya sites later that year (Early stages of the excavation at Uaxactun pictured right; photo by Anne and Charles Lindbergh).

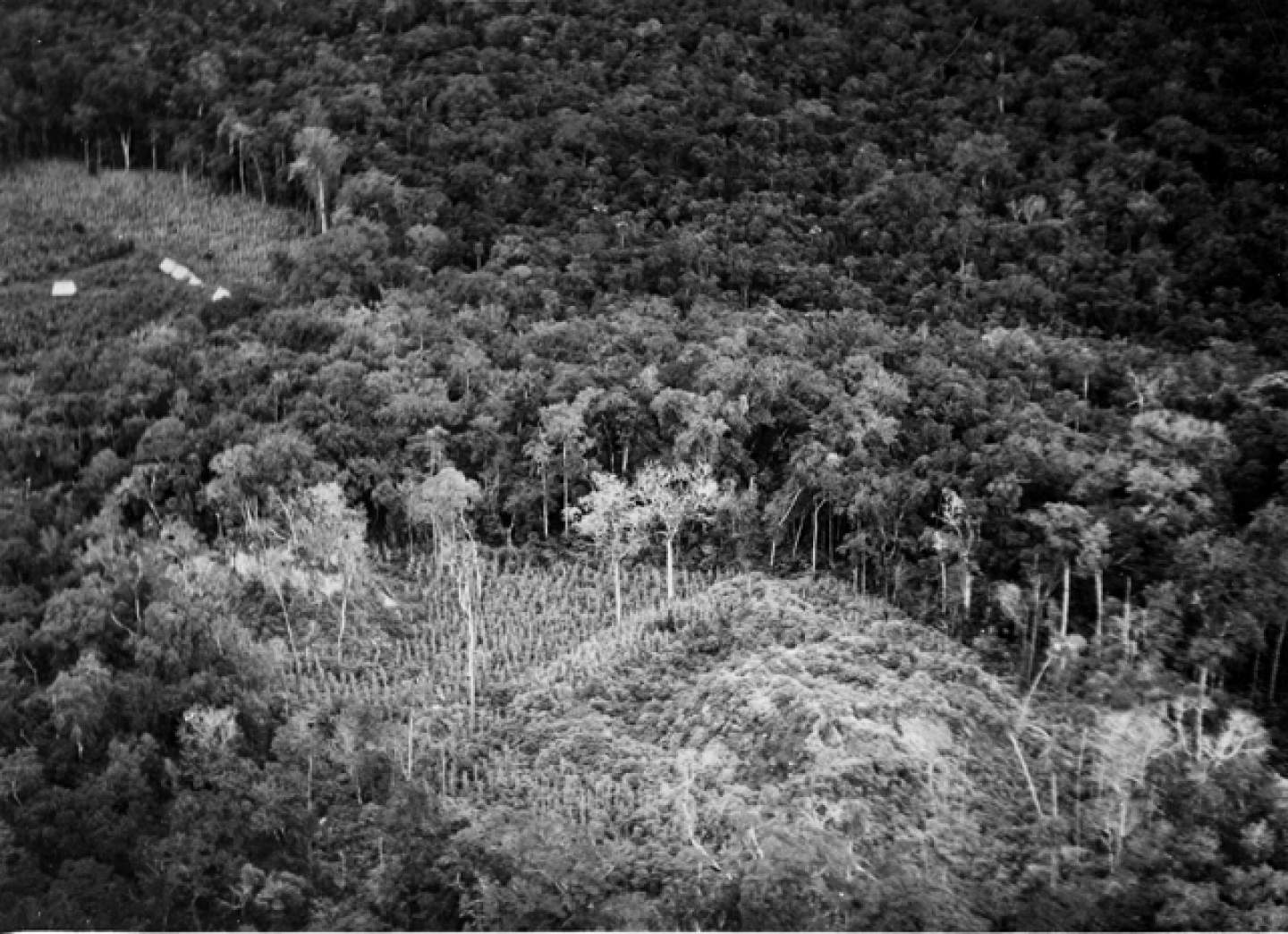

Since both Charles and Anne could operate the plane and cameras (primarily their Graflex RB Series C which took black and white photos) the couple was able to switch off flying and photographing, enabling them to collect a large amount of data during their surveys of remote areas of British-Honduras, Guatemala, and Campeche, Quintana Roo and Yucatan in the southern Mexico peninsula. Most flights were flown at relatively low altitudes (between 152 and 450 meters) and at a “cruising speed” of 90mph so that Anne, Charles, as well as Kidder and fellow archaeologist Oliver Ricketson, Jr, could detect changes in elevation at eye level and investigate vegetation before choosing what was worth photographing: mainly visible ruins and hydrological features.

The most extensive portion of their investigation took place in October of 1929 and a twin-motor Sikorsky Amphibian aircraft which they surveyed from for 25 hours over the course of 5 days. For Kidder this opportunity was somethings that “above all things,” allowed him to “get an idea of what the Maya country really looks like" (Kidder in "Five Days over the Maya Country", 1930 published in The Scientific Monthly)

Like we saw with the camera lucida, the Graflex RB Series C camera (pictured right) and the expanded vantage gained from the plane were technologies that allowed the archaeologist/techcician to access or represent the Maya landscape as it “really” was or objectively appeared. As in the case of Stephens and Catherwood accounts and engravings, the jungle appears in Kidder’s writing on aerial photography as something dense, overgrown, and disorienting, all of which inhibited the chance of being able to access the knowledge hidden within. According to Kidder, the outlook of archaeologists on the ground had often “been so stifled by mere weight of vegetation, that it has been impossible to gain a comprehensive understanding of the real nature of this territory once occupied by America’s most brilliant native civilization.” A turn to technology then allowed Kidder to claim a unique vantage point from which to know the “real” Maya history hidden in the jungle.

But as in the case of the camera lucida, it was not that these new technologies themselves produced ‘real’ and ‘true’ images. Instead, it was their correct use by a technician whose unique technical competence enabled them to construct an objective picture that produced them. We see this play out in Kidder’s writings on the subject in which he focuses extensively on the unique perspective he personally gained from his flight surveys, arguing that “with a little practice” one could go as far as to identify things as complex as the “sort of terrain the Maya were accustomed to pick for their temples and what varieties of trees flourish on the soil best fitted for their system of agriculture" with just the naked eye.

However, as some critics looking back on Kidder’s work have noted, despite these bold claims he never really worked out a systematic way to apply his hypotheses and links he came up with in the air never produced robust data set or anything that might substantiate the supposed correlation of vegetation types and temple on the ground (William Saturno et al.). Ultimately, Kidder’s hypotheses derived from this aerial perspective were more a product of his naked eye observations and visceral judgements than they were a careful or systematic analysis achieved through studying the black and white photographs produced from these flights. This is not to say that aerial photographs were not used to form more accurate and detailed understandings of the Maya landscape at this time. In fact, they often proved valuable for identifying new features and architectural relationships at sites both familiar and unknown to archaeologists producing these photos. However, it is important to note that Kidder’s use of flight and photography created an interpretive framework that, similar to Stephens and Catherwood’s framework of the camera lucida, did not perfectly or wholly capture an objective history of the Maya via technological improvement. Instead, this framework required that technology be used by the technician in ways that aligned with other social and political contingencies of the archaeologist’s identity in order to be of any meaning: and in the years of big digs like Uaxactun, this still often meant using the tools available to maintain the image of a scholarly gentlemen.

Scrollmation photos from Yale University Library: Accessed Smithsonian.

Though many from Kidder’s generation went on to hold long term positions in institutions like the CIW (unlike Stephens and Catherwood who never became Mayanists in full time positions), many of these men approached their work from a similar social standing as the amateurs that came before them. A large contingent that assumed the most prominent positions at the largest projects like Uaxactun and Chichen Itza were associated with Harvard university and even more specifically the all-male Fly Club at Harvard college. Although these projects occurred 80 years after Catherwood and Stephens’ time, the field notes and diaries from the largest digs between the World Wars reveal that many of these men still thought of archaeological projects as inherently adventurous and masculine pursuits (Black 1990). As such, it is important to keep in mind that the development of aerial archaeology was caught up in many of the same notions of mysterious adventure that had influenced the earliest searches for ruins in the 19th century and drew upon a similar framework of discovery that was as much social as it was technological. As in the previous era, the technician was taken up as an identity that was generally used to bolster claims of objectivity that extended beyond technical observations such as Kidder’s naked eye judgments. The archaeologist as technician in the case of early aerial photography demonstrates that perceived technical competency often went much further in evaluations of truth than analyzing the data that various technologies produced in a vacuum.

Temple I, of Tikal's Central Plaza rising out of dense forest (Guatemala)

Aerial Photography: Kidder Photos From CIW now Housed at Harvard

Uaxactun E-VII Sub East in early stages of excavation, Department of Petén, Guatemala.

Aerial Photography: Kidder Photos From CIW now Housed at Harvard.

Tikal's Central plaza today with much of the canopy cleared: National Geographic

LiDAR and The Remote Sensing Revolution

Image: National Geographic/Wild Blue Media

The Technician in Remote Sensing

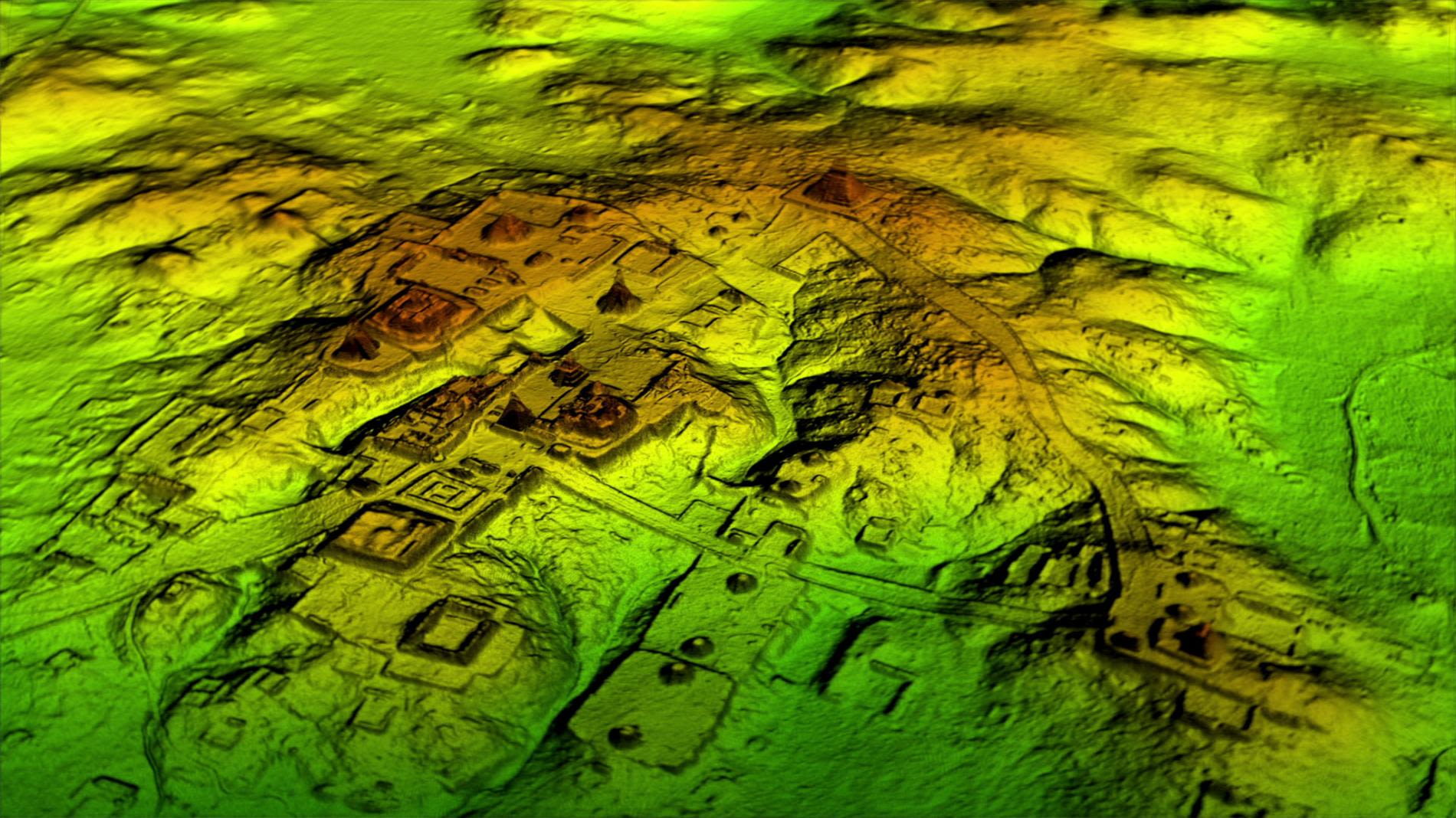

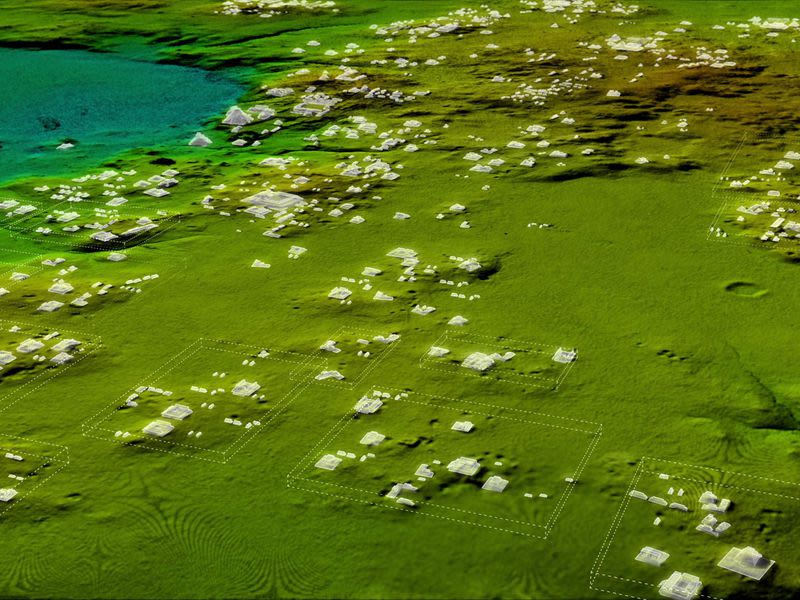

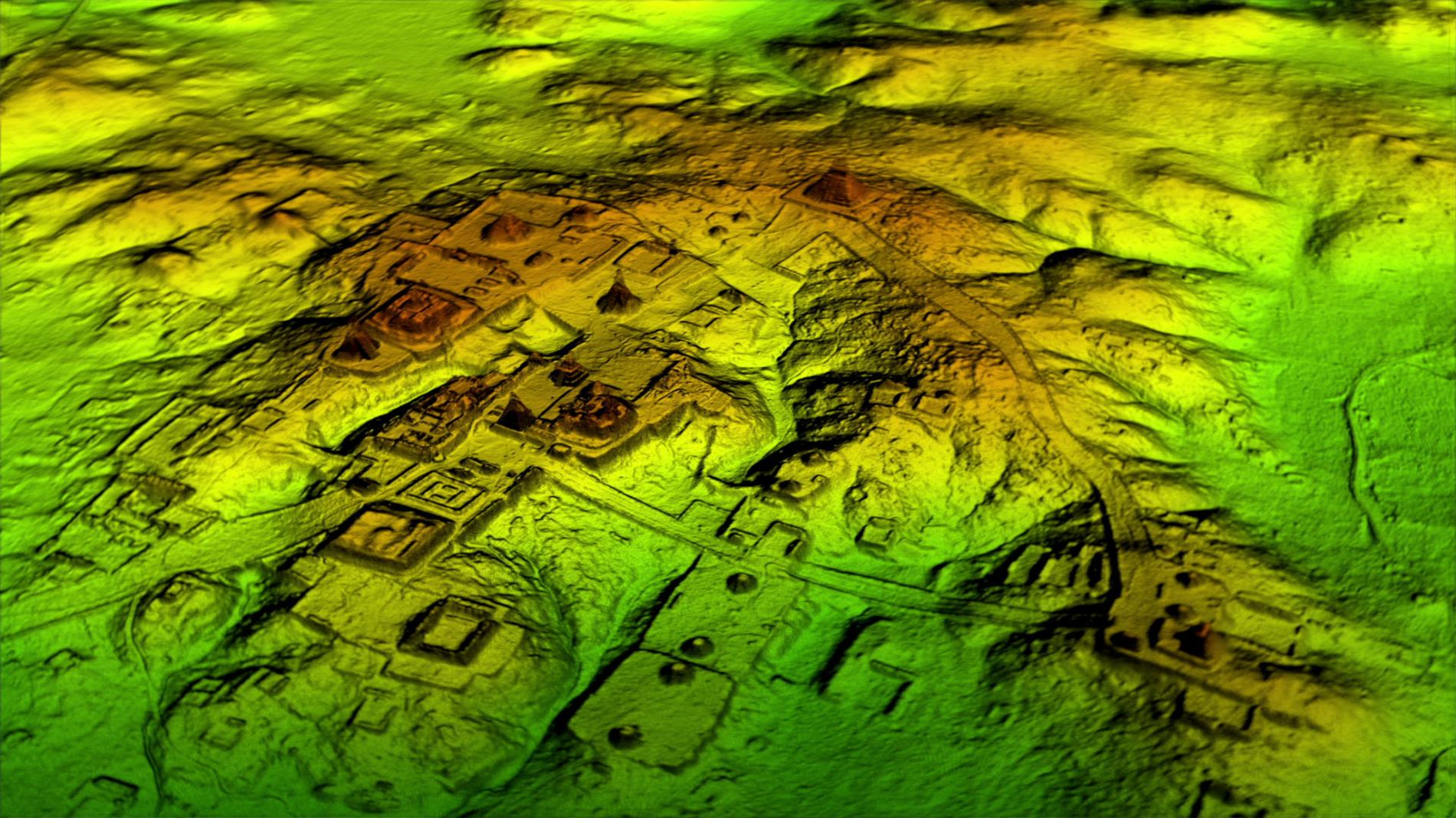

Though Kidder’s framework for understanding the Maya was a product of his time with clear historical roots in the mid-19th century, his embracement of flight and aerial photography as technologies that revealed trends across ancient Maya regions marked the beginning of a wider popularization of landscape approaches to Maya archaeology that have become increasingly central to the field today. As such, it is important to analyze how the archaeologist as technician fared through this transition and adapted to the more systematic approaches to landscape studies archaeologists employ today (Pictured Right, LiDAR digital elevation model of Caracol; Chase et al 2015).

While it is outside the scope of this page to give a complete history of remote sensing techniques, by the late 1980’s the convergence of GIS (Geographic Information Systems), GPS (Global Positioning Systems), Multispectral Scanners and a host of other technologies allowed landscapes to be analyzed from increasingly diverse perspectives. While only a minority of archaeologists like Kidder had access to high quality tools to take aerial photographs in the early and middle 20th, by 1999 with the launch of the IKONOS Satellite more scholars and even the general public began to have a much easier time accessing high-quality spatial data. However, what has undoubtedly been framed as the most important remote sensing development in Maya Archaeology is the even more recent use of LiDAR.

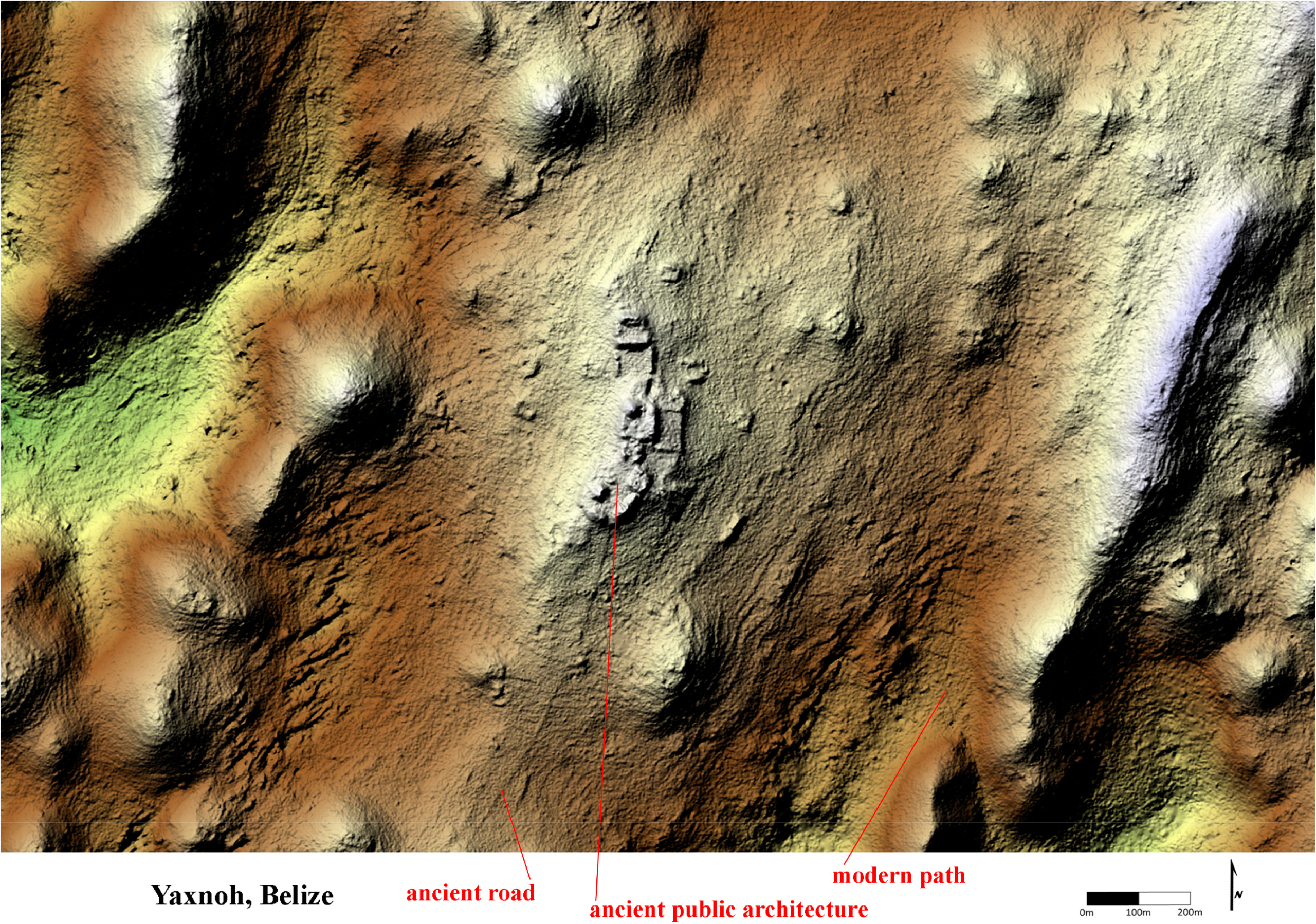

(Pictured Right, LiDAR model of Tikal: National Geographic/Wild Blue Media; Pictured Below, Gif of LiDAR Process via Eagle Mapping)

LiDAR, which stands for Light Detection and Ranging, is a remote sensing technology that sends light in the form of pulsated lasers that measure the distance from the airborne system used to collect the data (usually a plane or helicopter) and whatever is below it. Though not developed with Maya Archaeology specifically in mind, LiDAR has allowed for complex 2-D and 3-D maps to be produced for individual sites and larger landscapes, even those beneath dense vegetation found in places like the Peten rainforest. Within academic literature the application of LiDAR in Maya archaeology has been described as nothing short of a “Geospatial Revolution” [Chase et al 2012], facilitating a paradigm shift for spatial analysis of an equivalent or greater importance than developments in time and temporality studies from the mid-20th century following the advent of radio carbon dating.

As with the camera lucida and aerial photography, conversations about LiDAR - even in academic archaeology - have focused largely on its capacity to uncover a civilization that is “still obscured by inaccessible forest" (Canuto et al 2018). This tendency to focus on the inaccessibility of Maya sites due to the dense jungle they rest within is a theme that has survived since Stephens’ time and is still quite pronounced in popular representations of LiDAR and remote sensing today, such as in publications and documentaries put out by National Geographic (see video below).

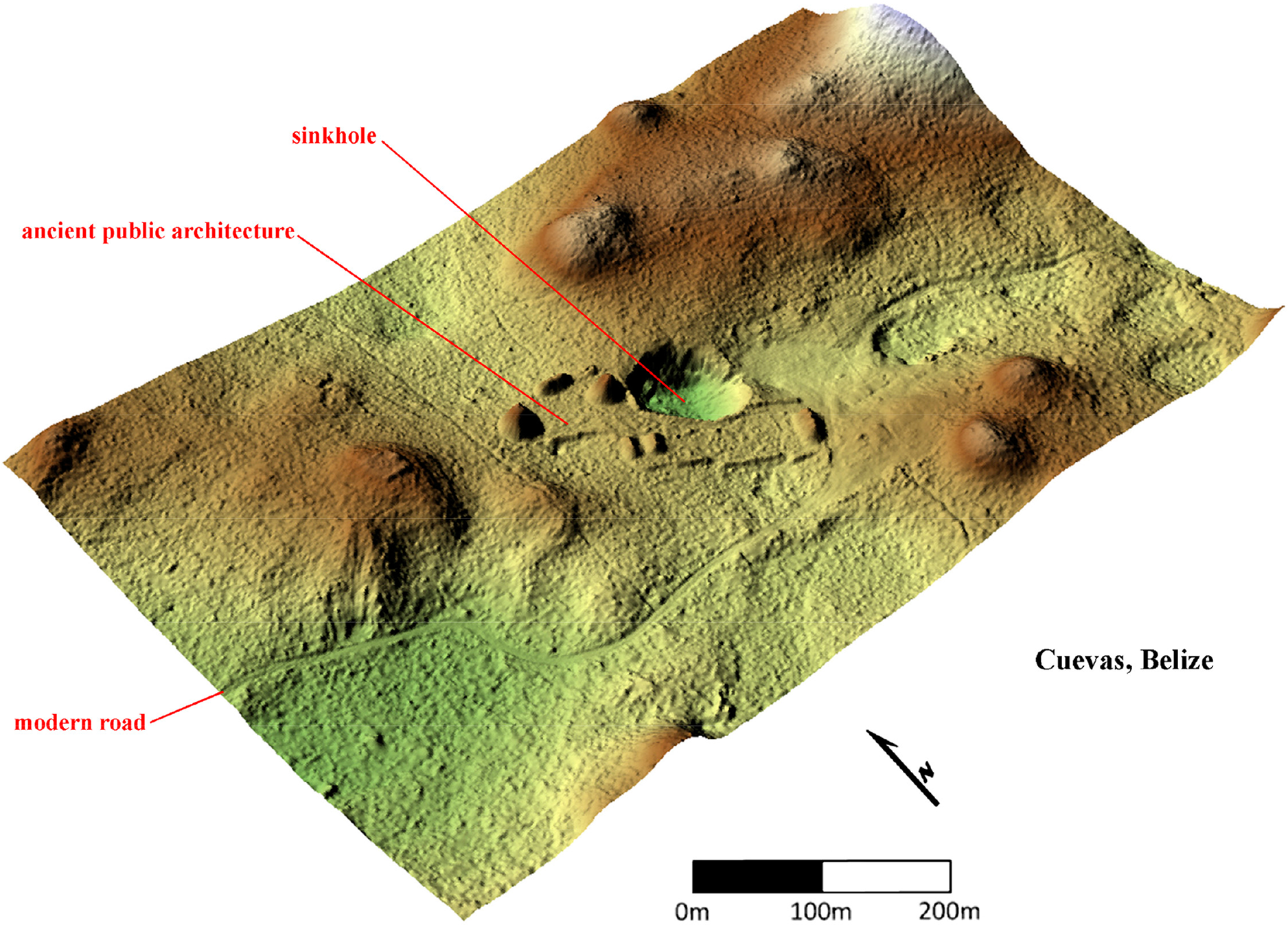

Image: Site of Cueves from Chase et al 2013; shown here roads and sinkhole illuminated via LiDAR

Example of LiDAR in more popular media

Example of LiDAR in more popular media

Although Nat Geo consults professional archaeologists to create their articles and documentaries about LiDAR, which do contain sound and reliable information about how they work, they also go to great lengths to emphasize the adventurous and mysterious results of LiDAR surveys. As shown in the preview for the documentary “Lost Treasures of the Maya Snake Kings”, LiDAR surveys are considered most interesting for their potential to yield exciting ground truthing missions that take the technician from the lab out into the field to test what they’ve learned. While Albert Lin (the consulted engineer/archaeologist) of this documentary is asked to provide some background on how the LiDAR data was collected and analyzed, the larger focus centers on his actual adventure into the jungle to see with his own eyes what the remote sensing data he is technically literate in and uniquly able to read tells him should be there.

Lin emerges in this documentary as a competent technician, someone who is able to read the complicated but objective data and translate it into knowledge about the past. Additionally, these missions are usually set against a comparative backdrop of ancient Maya technology which we are constantly reminded come from a “stone age” civilization. As popular articles are quick to inform us, “[t]he ancient Maya never used the wheel or beasts of burden, yet this was a civilization that was literally moving mountains.” The ancient Maya emerge in moments like these as mysterious but competent technicians themselves, the creators of art that defied representation since Stephens time and whose complex settlement patterns defy our understanding to this day, even despite their supposedly rudimentary technology. The identity of the modern technician is revitalized here by positioning Maya civilization as something that defies easy access and translation despite its simple technological character. Newer, cutting-edge technology, in this case from LiDAR, emerges as the most objective way to see through and understand these simpler technologies. Again, the technician becomes the one most suited to interpret what is really out there.

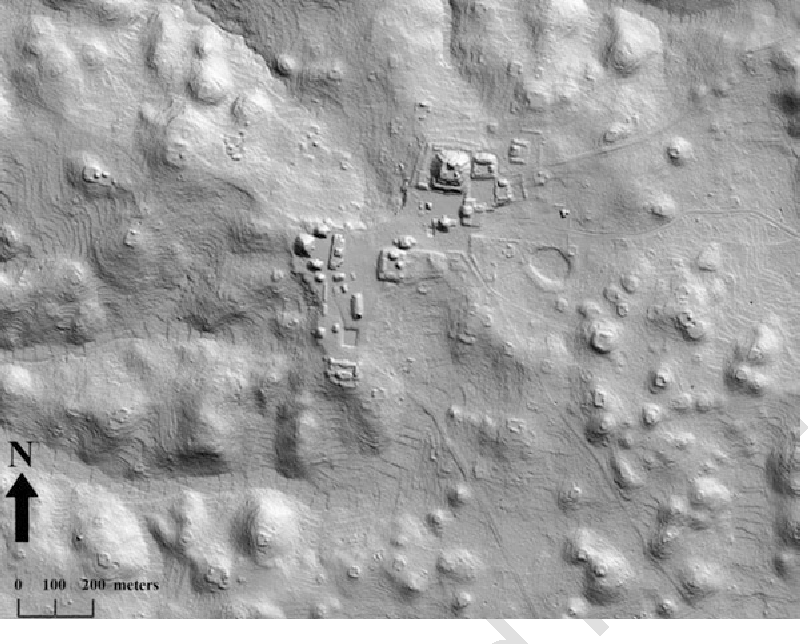

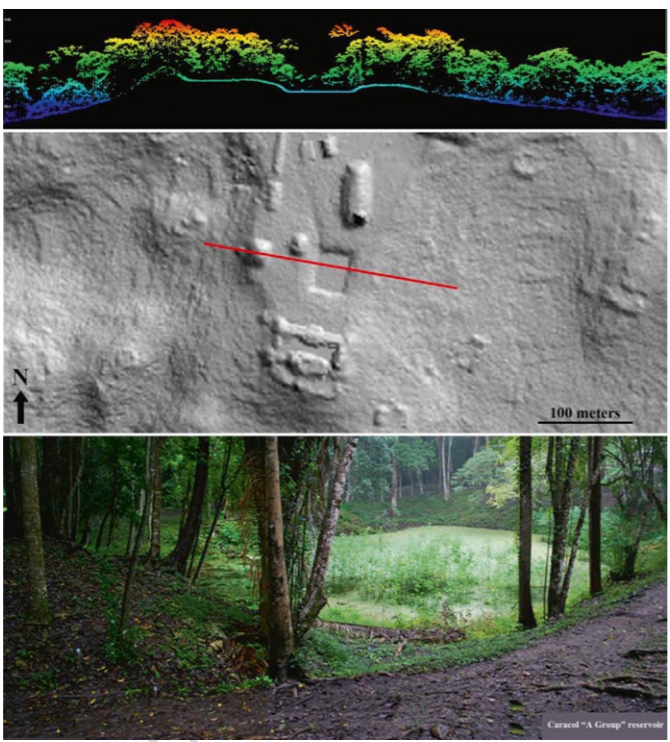

Here it is helpful quickly turn to images of LiDAR to consider how the data is generally organized and what its proponents claim it does differently. To take an example from Caracol, the field site of two of the most influential landscape archaeologists Arlen and Diane Chase, we can consider how LiDAR has been used as an instrument of 'seeing'. In a paper written with Dr. Weishampel, the two show how LiDAR could be used to create an incredibly detailed 2-D map of the Caracol's “A-Group” reservoir (middle image), able to clearly show slight changes in elevation that allowed for the analysis of the reservoir relative to its surroundings.

What is framed as remarkable about being able to look at these elevations is that they were obtained through dense canopy cover (pictured top). It was the use of LiDAR lasers that could penetrate enough gaps in the canopy that enabled the production of a comprehensive image of the floor. Compared with the ground photo of the site (bottom), the LiDAR map is argued to say a lot more about what the reservoir exists in relation to and its broader spatial qualities.

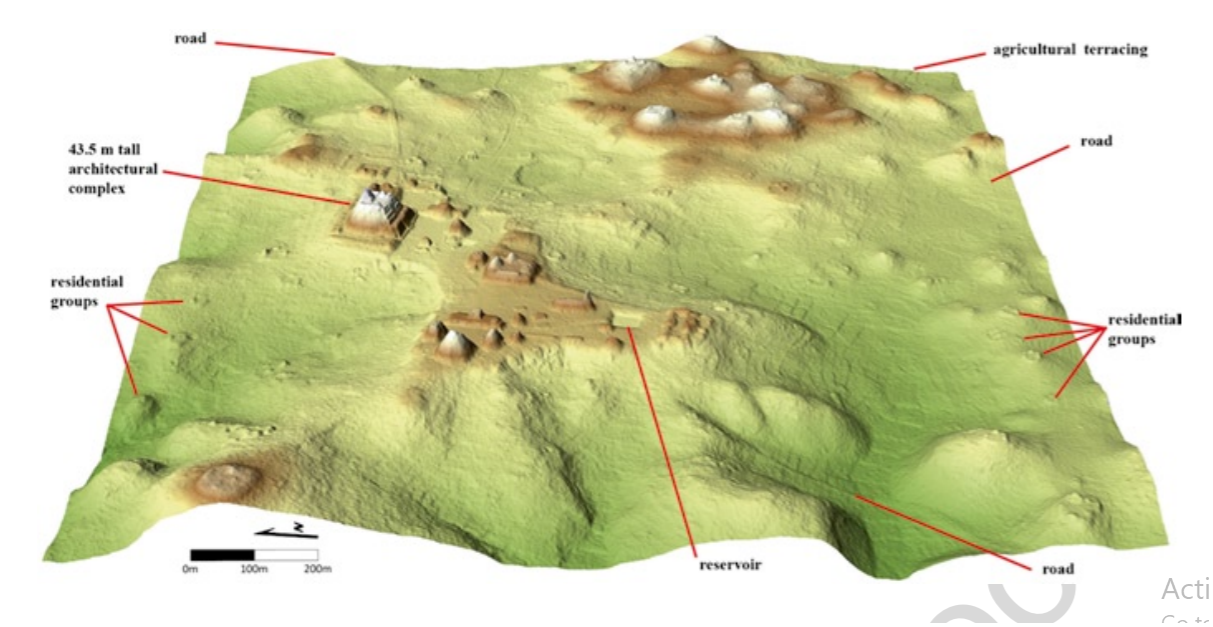

As such, LiDAR is said to “overshadow the data gained from traditional mapping,” because of “the potential of this technology to see beneath a jungle canopy.” In fact, LiDAR allows the entire city of Caracol to be “seen” at once beneath the canopy cover, something that cannot be done with aerial photography or the naked eye; the real or true image is one that can only be seen with a specific technical literacy. (Chase et al, 2013).

(Pictured Right: Wider view of Caracol including roads, reservoir, residential groups and other difficult features to pick up with typical photography)

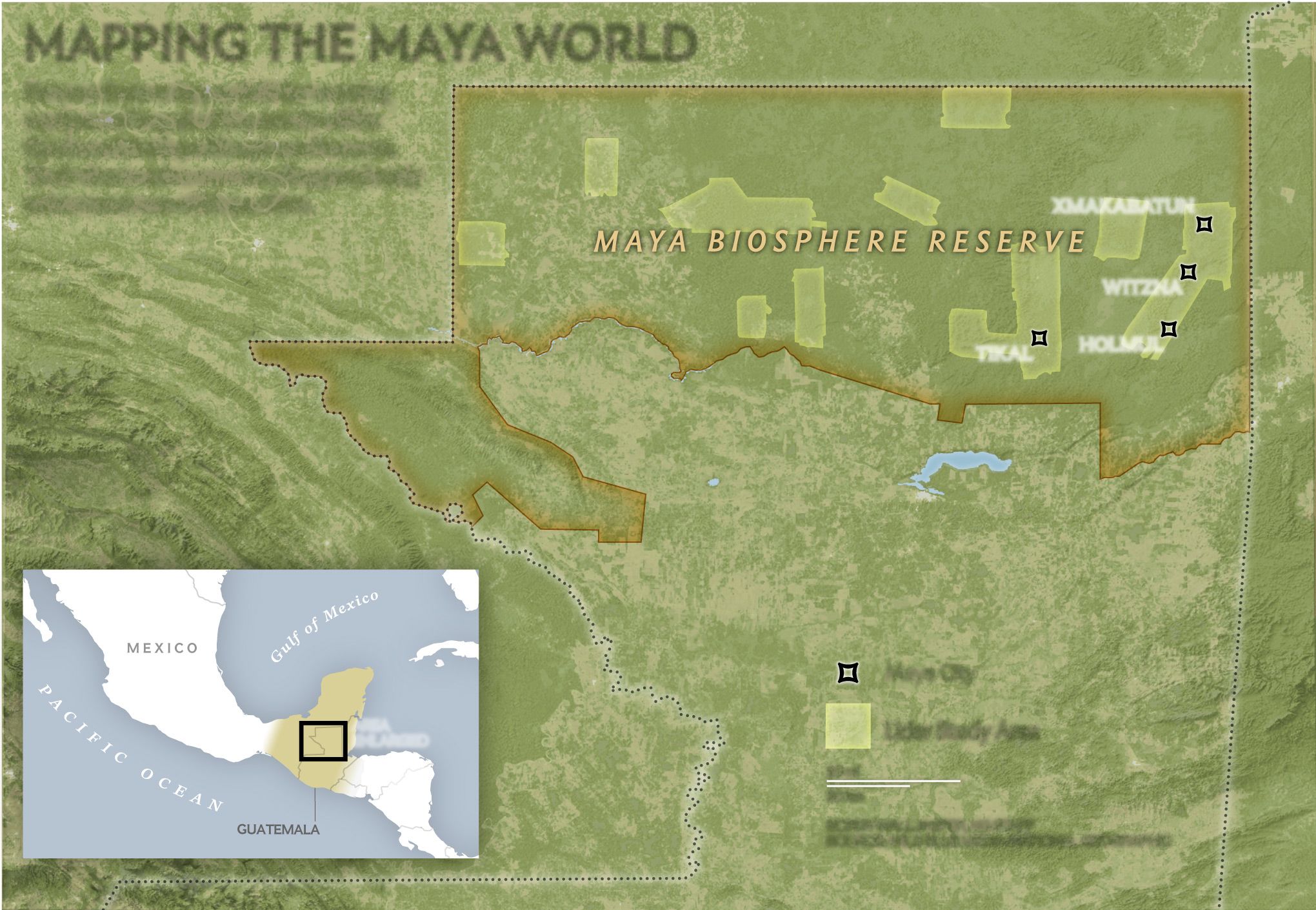

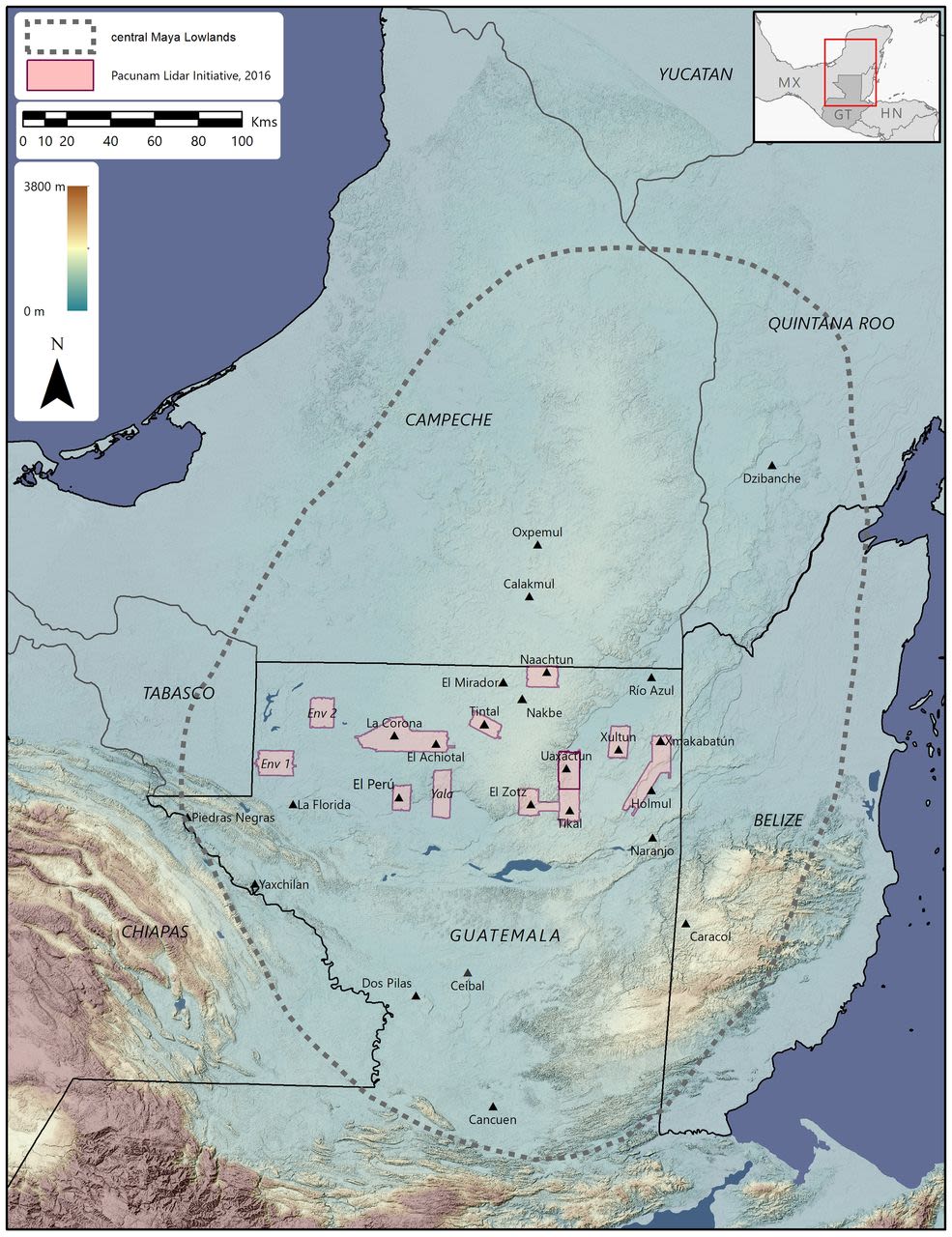

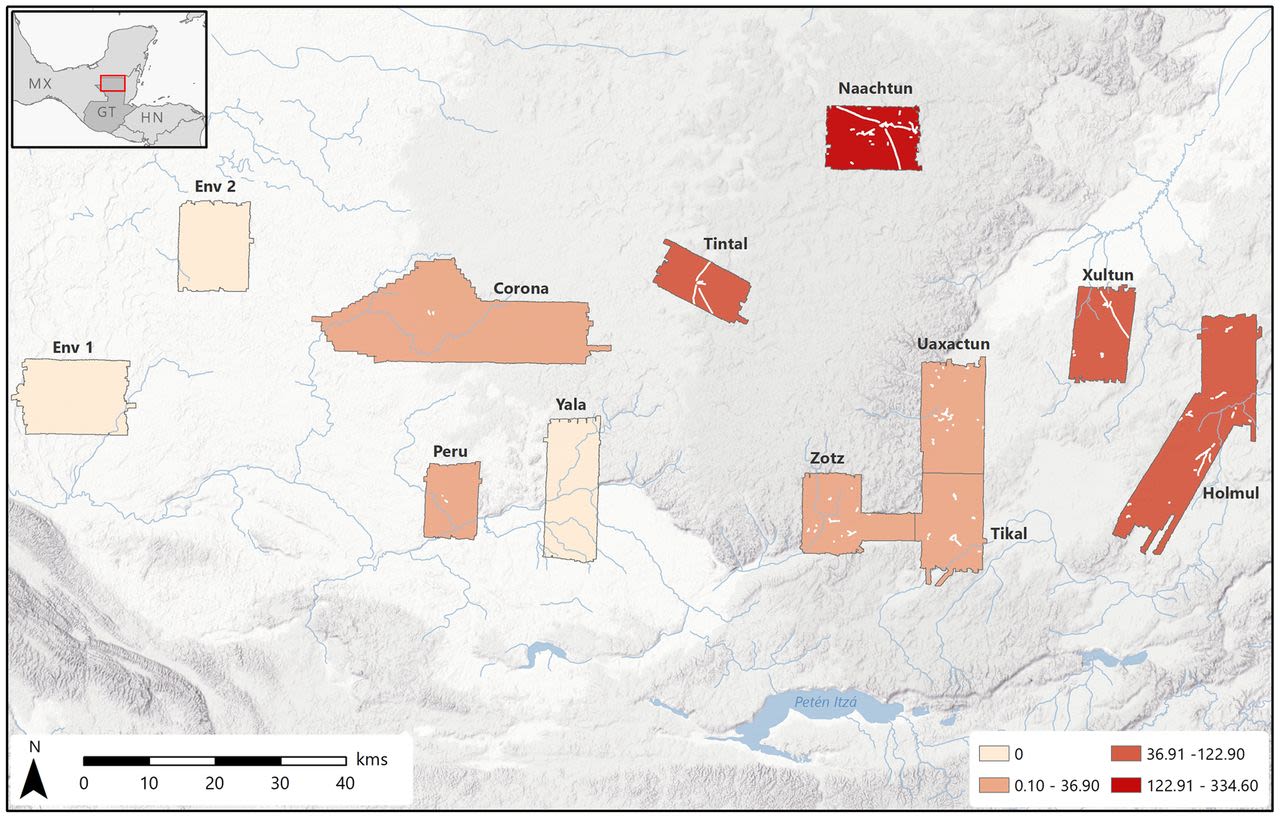

Analysis of the largest Maya LiDAR initiative, the Pacunam LiDAR Initiative (PLI) which mapped 2114 square kilomiters of the Maya Biosphere Reserve in Guatemala, uses similar terms to describe the potential of the new technology. Since ancient Maya sites are “still obscured by inaccessible forest” today, LiDAR becomes a necessary means of constructing a total image of the landscape. The constructed landscape, in turn, is one that must be interpreted by the capable technician.

(Maps of the survey area pictured right Maps Cuanto et al 2018)

However, it is not the case that the landscape produced is one that can be translated by the technician in a vacuum. Looking at the distribution of the 12 PLI survey blocks we find that it is a disjointed mosaic with strips and pieces spread out across the MBR which stop at the boarders of Mexico and Belize. As such, the image produced is one that conforms to national boundaries that the Maya did not themselves conceive of but which the archaeologist does. Further, the image produced is also one that maps onto already well-established sites of field research that have a significant amount of data collected through excavation that the LiDAR results can be compared. Here LiDAR does not emerge as a technology that simply constructs an image that can be used to know the Maya completely on their own terms. Rather, LiDAR is employed by the technician who is themselves caught up in a variety of socio-political limitations (modern borders), alternative and complementary methodologies (field work), and, often not so obviously, the aesthetics of discovery that frame current projects in terms inherited from the earliest forays into the field in the mid-19th century.

All this is not to say that the use of LiDAR is not special or revolutionary to the field of Maya archaeology or that the data produced from LiDAR surveys is subjective and totally up to the personal interpretations of archaeologists. To the contrary, mapping the history of the technician through the development of archaeological LiDAR technologies should allow us to appreciate the very real societal influences and histories that have operated on the technician and which have enabled them to create the present frameworks from which they create spatial data and then analyze it. Catherwood’s drawing’s and their romantic aesthetics, Kidder’s theories derived from aerial perspectives, and the thousands of digital elevation models produced via LiDAR all highlight the historic centrality of social and technological translation and the importance that the archaeological as technician has often placed on situating technologically derived data at the intersection of a variety of competing and reaffirming influences of our own societies.

The fact that thousands of archaeological structures and features have been found using LiDAR and are now able to be analyzed from a broader regional perspective must not be understood as the consequence of technology simply forcing itself forward because that’s what technology does. Rather it must be understood as a consequence of various historical influences coming together under a new interpretive framework that enables particular questions to be raised and particular answers to found at a previously unavailable scale. The identity of technician is best understood as one of these unique historical influences and should be critically considered when thinking about how archaeologists construct their data and how that data informs the historical narratives they build.

Illustration Revisited

Pictured, Heather Hurst and team preparing to illustrate cave paintings at Oxtotitlán, Guerrero, Mexico; Photo by Joseph Gamble

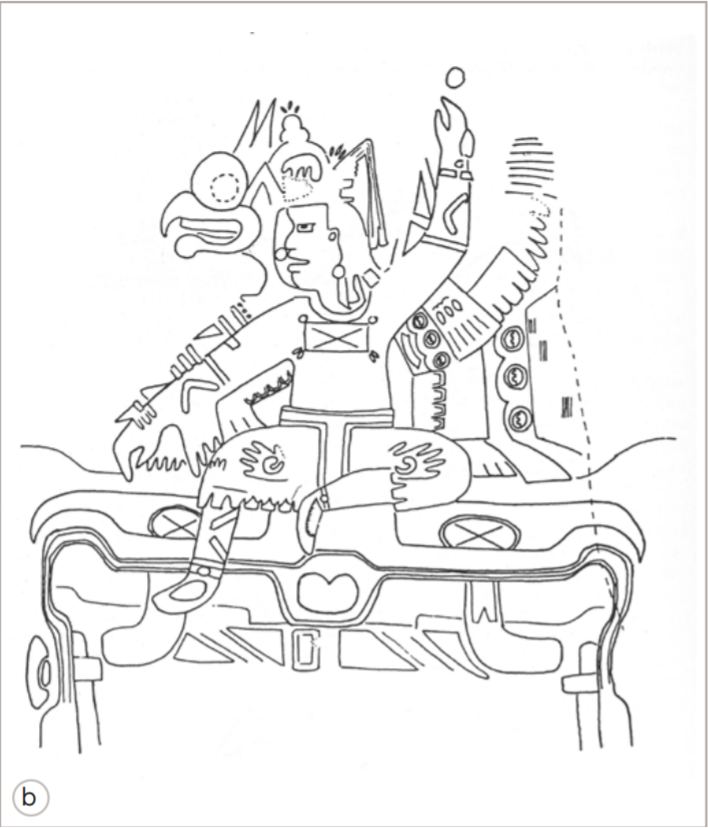

A final technology to examine is that of illustration as explored by Heather Hurst. In her project on “The Artistic Practice of Cave Painting at Oxtotitlan, Guerro Mexico” Hurst explored ancient technologies through the cave paintings of Oxtotitlan and their unique temporality. By illustrating the cave paintings using a variety of technologies, it became possible for Hurst to reconstruct the “symbolic vocabulary, calligraphy, and paint technology,” that the ancient painters used to make their paintings. This allowed Hurst to ask more nuanced questions about their temporal qualities and their layered contexts within the larger landscape of Guerro. For example, by drawing the paintings herself, Hurst was able to determine the brushstroke sequence of the original artists and in turn determine that they had symbolically “dressed'' certain figures according to a meaningful process that fit within the logics of the landscape that the painting was embedded in. Hurst employed various contemporary technologies to create her illustrations ranging from multispectral imaging to detailed forms of measurement, but the most important remained the act of drawing. Hurst appears as a technician here, but one who is primarily concerned with using technology to access meaning through considerations of processes. It is through the process of painting that she is able to link together a common symbolic language that is deeply local and temporal.

(Images 1 & 2: Oxtotitlán Panel C-1. Photo and illustration by David C. Grove: Seated throne figure)

Hurst’s emphasis on sequence and historic context is useful for thinking about LiDAR and GIS in archaeology which are technologies that produce maps that are typically layered and which have powerful potentials to link temporal relationships to spatial elaborations. When looking towards the future of archaeological technologies of “seeing” then, it might be helpful to center continuities in processes of data collection that technicians have historically gravitated towards and ask how they are still informing data collection and presentation today. As such, although it is important to frame the unique interventions that technologies like LiDAR make to more fully appreciate the unique things they can do, it is equally important to situate them within a larger historical process of identity making that began over 160 years ago and is still maintained in various from in the discipline today. Many archaeologists have become particularly attentive to historic processes and connections revealed on the landscape via LiDAR and have used them to break down unexamined assumptions of things such a strict Maya rural-urban divide [Garrison et al 2019], to map the development of complex building practices across time and place [Hutson 2014], and to build regional landscape models that center complexity and temporal depth of both household and settlements [Chase et al 2013]. However, it is possible that such projects could be further strengthened by being more attentive to the frameworks data is collected within and from which they are analyzed, one of the most prominent being the archaeologist as technician. As in Hurst's project, technology seems to work best when it is not used to displace older methods for the sake of newness, but to compliment processes of data collection that the scholar recognizes as a particular and specific kind of framework with deeper historical roots.

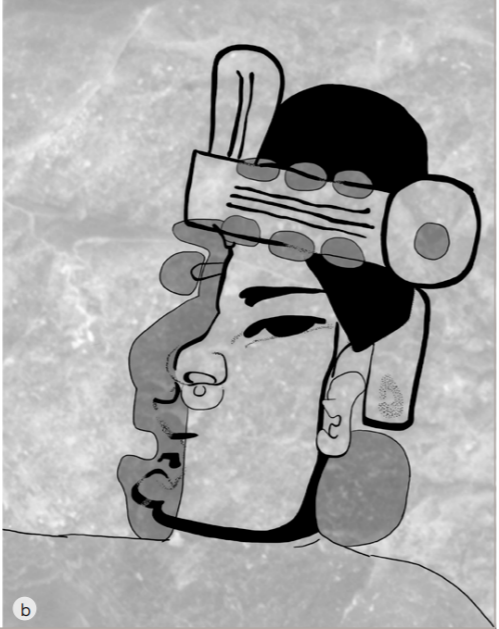

Image 3: Detail of human face of Oxtotitlán, image by Joseph Gamble; and rectified to measured field drawing by Heather Hurst.

Image 4: illustration of human face of Panel 1-03 by Heather Hurst and Leonard Ashby.

Conclusion

The technician appears throughout the history of Maya archaeology as an identity used to argue the objectivity and unique insight of the scholar or explorer employing it. However, this objectivity is never the technology's doing alone. The use of technology constitutes just one part of the technician's identity in any given era with the rest being made up of separate but related appeals to the technician's various social and political competencies or knowledge. This is not to say advances in technology do not change the way archaeology is practiced or increase the general precision of the data archaeologists have access to; in fact, the opposite is often true. However, such changes are best set within the longer history of technological usage and change where it is possible to understand the influences of the past on present practice. New technologies yield their best results when they are used to ask questions they are capable of answering. Asking the right questions becomes much easier when the framework from which they are asked is historically situated and apparent to those asking them. Ultimately, understanding the influence of the archaeologist as technician can be helpful for understanding both the history and stakes of how archaeological data is collected and is relevant to any project that uses technological tools to search for answers about the past.

LiDAR bare earth rendering of the newly-found site of Yaxnoh, Belize (Chase et al. 2014)