Hearing the Mayan Voice

How re-examining archeological artifacts and paradigms help us form a narrative that comes directly from the source.

I N T R O D U C T I O N

This page explores how common misconceptions of the Maya could have been avoided if we as scholars placed more importance on the pre-Hispanic narrative coming from the Maya themselves. Through looking at artifacts that highlight the Maya voice, we can re-evaluate existing paradigms in a new light to better contextualize the field of Maya archeology.

Palenque. Chiapas, Mexico. Many Maya sites are considered to be "hidden" in the vastness of the jungle.

From its origin, Maya archeology was framed in a way that directly excluded the Maya from making any contribution to the body of knowledge. Early archeology was conducted exclusively for a white, western audience with research conducted by white, western archeologists. These elites brought forth their own biases that then clouded their discoveries and analysis to follow.

Harvard Fly Club members and company during a field season at Uaxactun, Guatemala. Uaxactun is often cited as the origins of Maya excavation archeology.

In re-examining various archeological artifacts to better understand the voice coming forth from the creators themselves, the prehispanic Maya, we see that archeology has largely erred in its exclusion of them, limiting their authority and narrative. These exclusions form biases would go on to influence beyond the imaginable scope, creating an erasure of their modern descendants and creating an inaccurate body of knowledge. By holding these biases in a critical light, we can raise our awareness and move forward in the discipline of Maya archeology

Large Incense Burner, Artist Unknown. Some biases like the idea that cities are remote and "hidden" for a long timed caused scholars to doubt Mesoamerican interconnectedness and trade.

The Peaceful Maya

By clouding our analysis and findings with personal judgment, archeologists and scholars create a narrative rooted in misunderstanding. For many years scholars ignored obvious evidence and continued promoting a warped narrative rather than a clear, authentic account from the Maya themselves. One of the clearest examples of archeologist's steadfast hold to their biases is the wide acceptance of pre-Hispanic Maya as a peaceful, languid population.

Archeologist David Webster, who had dedicated a large part of his life's work to debunk the notions of docile, subservient Maya, recounts how when an amateur Mayanist was faced with the reality of Maya planning and calculating for warfare through the creation of causeways and fortified architecture, lamented “Somewhere… there must have been a peaceful civilization.” Yet, the reality was widely different. With the discovery in years to come of graphically violent murals, evidence of weaponry, and fortified architecture, the idea of the pre-colonial Maya as a peaceful utopia would crumble.

However, time cannot be credited with people suddenly rising to their senses, as these archeological evidences that would later on clearly debunked the myth of the Peaceful Maya were always present. From Maudslay’s Usamacinta regions to the first surveyor of Bonampak, monuments and artifacts of warfare always existed at these sites. So why did it take so long for archeologists to truly finally see what was in front of them?

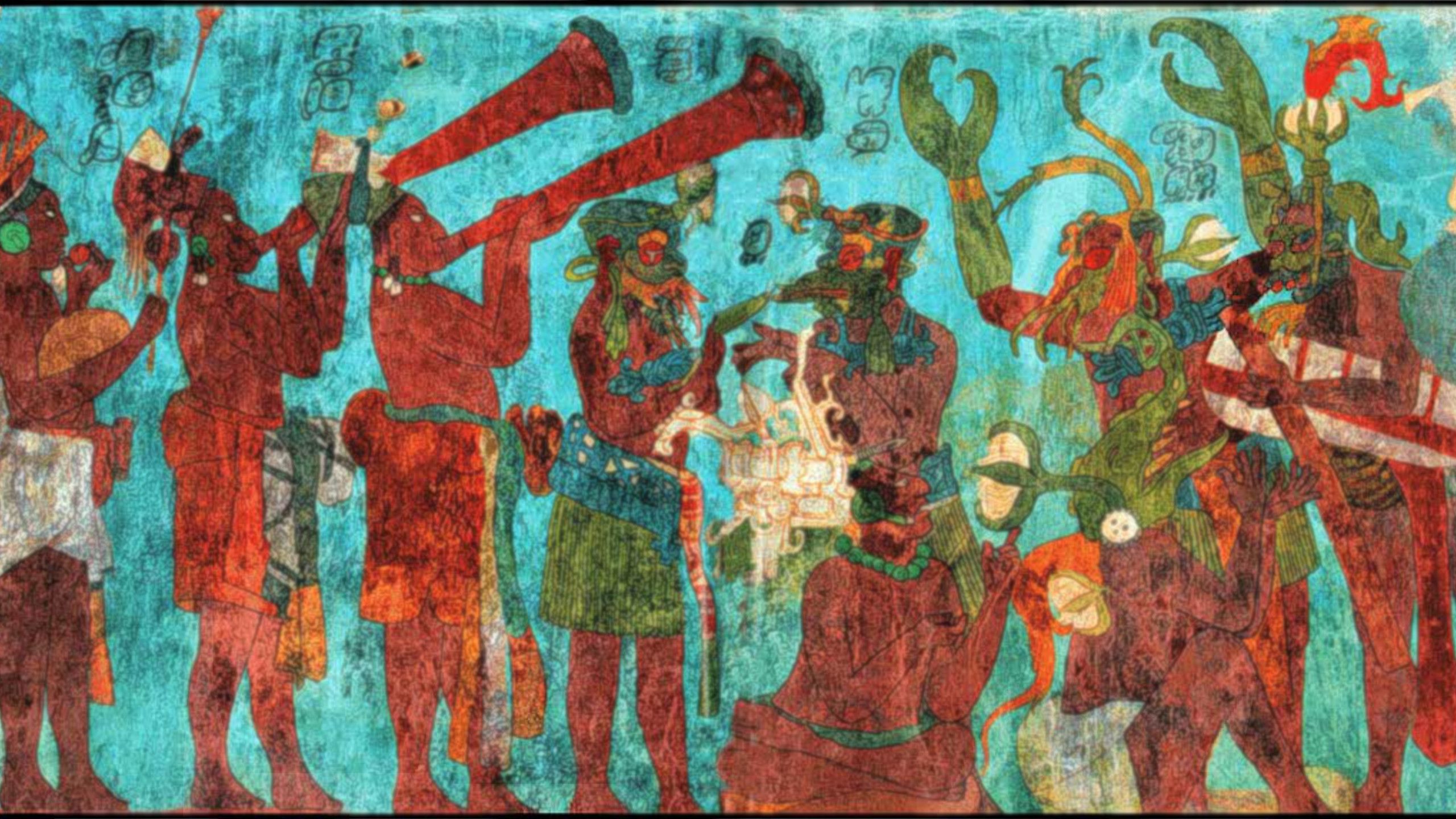

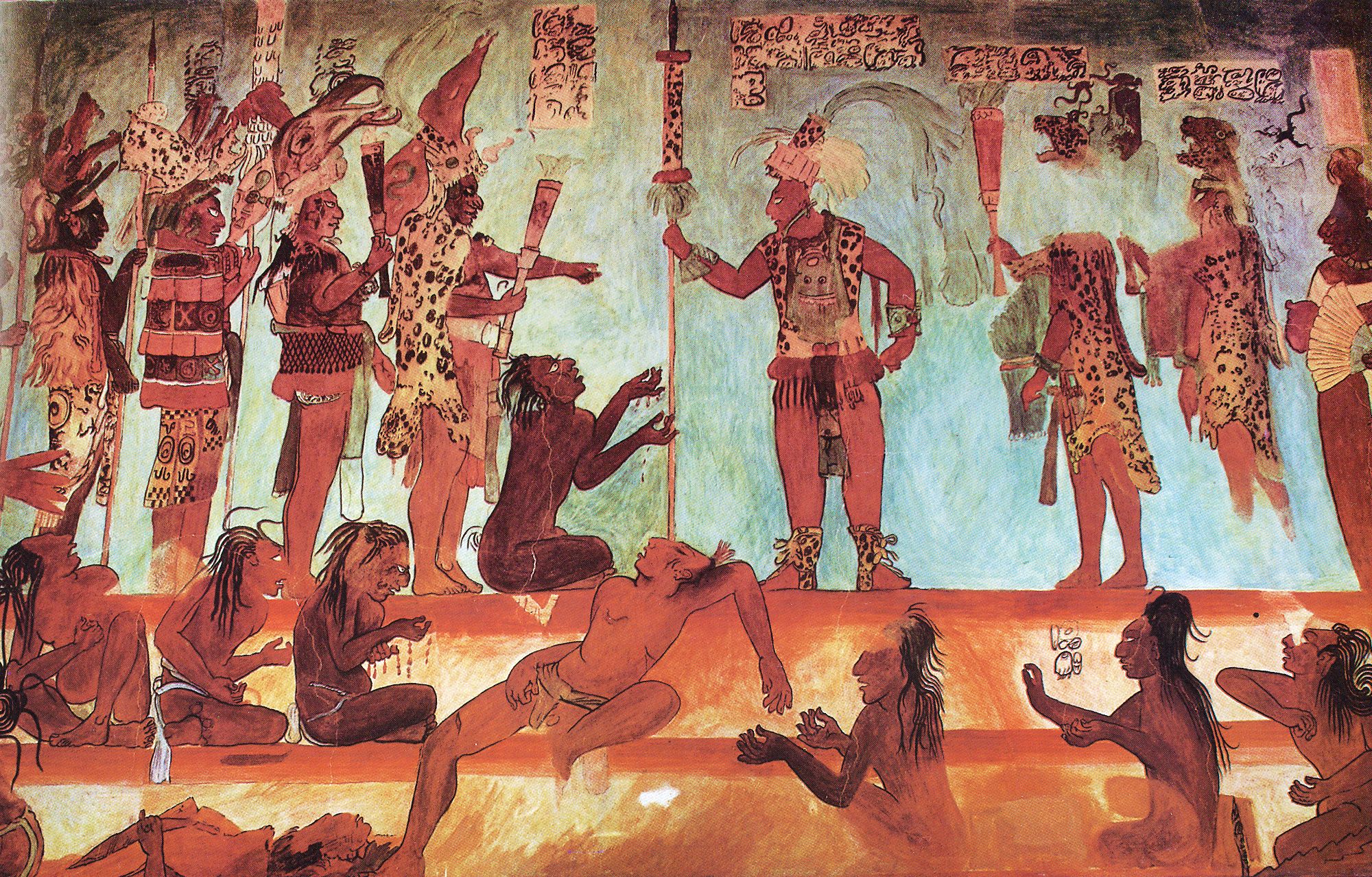

Bonampak, Room 2. Guatemala

Bonampak, Mural of Captives. Room 2.

Bonampak, Mural of Captives. Room 2.

Webster points to the innate need to reflect an emotional refuge onto the past;

"I felt a twinge of guilt that my work had so disillusioned him, especially right in the middle of the Vietnam War, when one needed all the mental refuges one vould ind. His attitude was a classic example of the widepsread propensity to appropriate the past as a kind of emotional Shangri-la"

By establishing pre-modern time civilizations as halcyonic, idyllic spaces, we are able to escape from the turmoils of our present-day scenarios, such as wars. But we know that warfare is not a relatively new concept, war has existed for eons and seems to be truly inescapable. The evidence of fortresses and imagery of captives that were abundant after deeper exploration of a site was ignored, and the Maya were early on written off as a docile population, whose reigns were ‘conspicuously lacking of warlike scenes, battles, strife, and violence” (Morley 1946).

Another early Mayanist, Sylvanus Morley, contributed to the first analysis of Maya archeology by not crediting the same artifacts he had stumbled upon (like the Bonampak war murals) as being authentic narratives but to have their analysis of these artifacts stay in the mire of their aesthetic qualities.

Although we have established this enactment of a status quo with essentially no archeological evidence in defense, we still can’t seem to create a sufficient explanation as to why early archeologists wanted the Maya to be peaceful. Stubbornness must be rooted in some justification, but for the large part archeologists like Webster relate this fixation with gentleness as the norm, sans any real justification.

In an attempt to defend those who originally proposed the gentle Maya as a norm, we can think about the complexities of the genealogy-lineage relationships early Mayanist followed. These genealogies of scholars meant in order to make it into the field you needed connections, hoping for someone who was established in the field to extend an olive branch, an invitation to become a fledgling Mayanist. The implications of this high reliance on existing archeologists in the field to continue these lineages can likely mean that younger, newer archeologists would not be eager to contradict the norms. If someone has put in the effort to invite you into their world and they tell you the law of the land, so to speak, it's very rarely seen that the apprentice becomes the challenger. Thus, reigning ideas such as the misconception of a tranquil Maya civilization were likely not challenged so as not to put a nouveau Mayanist at risk of being cut out of the ‘family tree’.

Despite these passes as justification as to how we got here, the idea of the Peaceful Maya has surmountable evidence against it. One of the clearest examples are the Bonampak murals in Chiapas, Mexico. When first discovered, these sites were admired not for their clear, evidential importance in the disruption of the paradigms but for their aesthetic merits (Webster). However quickly the murals were credited as the critical murals that overturned the previous notions of peaceful Mayas (Kinoshita). Through the discovery of the Bonampak murals in 1946, archeologists were able to juxtapose a “widely accepted model” with “coherent messages from the ancient peoples themselves” (Webster). Comparing these two narratives, created by anglo-Saxon archaeologists and those who were the direct subjects of the study, shows how paradigms shifted when subjects were no longer other-ized or underestimated but empowered and ‘heard’. When we accept that the “visual exceeds the verbal” we finally give validation to the voice of the Maya, and the words they were speaking painting finally fell upon hearing ears.

Warrior close up from murals at Bonampak.

Warrior close up from murals at Bonampak.

The ability to break away from the norms, such as acceptance of pre-hispanic Mayas as peaceful, allows us to see how our own personal idealistic biases greatly influence the facts and why it's necessary to hold findings to be critically analyzed. If we really wish to claim we know about the Maya and that we are making breakthroughs in the understanding of them, then we have to make sure our evidence is not clouded but the evidence that can help us pridefully progress knowing we have done the narratives of the Maya people themselves justice. With the Bonampak murals, we can see that the refusal to hear the voice of the 'subjects' lead to massive misunderstandings that likely warped other areas and other ideas of what we thought to be Maya.

Warrior Bas Relief. Chich'en Itza', Mexico

Warrior Bas Relief. Chich'en Itza', Mexico

Warrior Bas Relief. Chich'en Itza', Mexico

Warrior Bas Relief. Chich'en Itza', Mexico

Captured Warrior. Bas Relief. Chich'en Itza', Mexico

Captured Warrior. Bas Relief. Chich'en Itza', Mexico

The Lost City

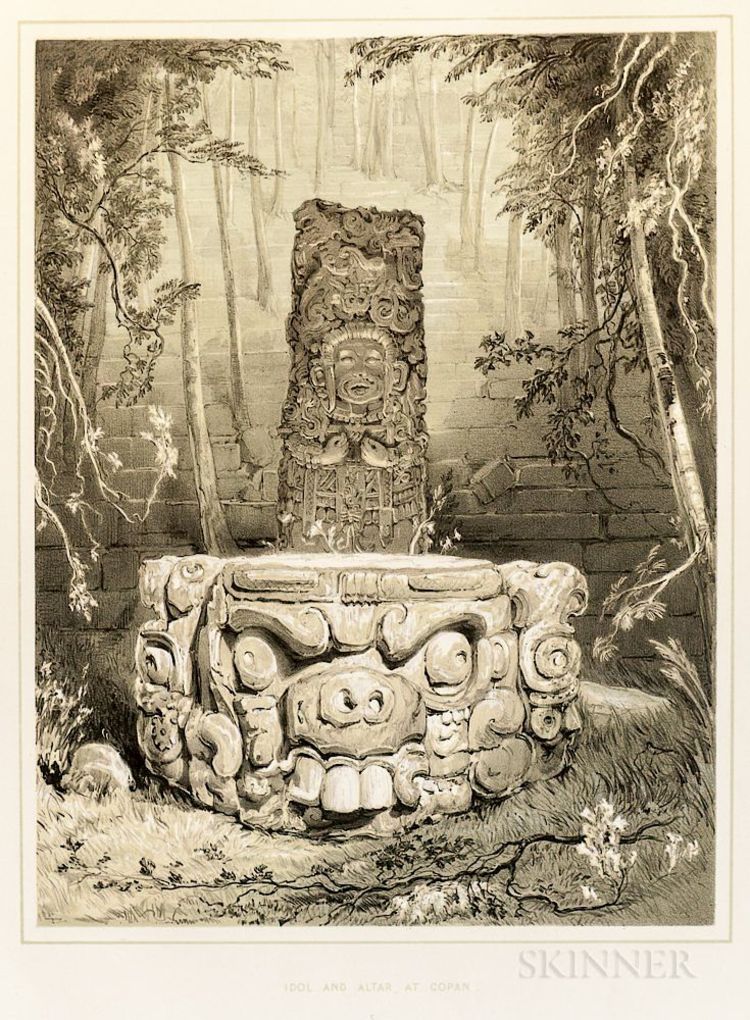

Catherwood drawing from Incidents of Travel. His artwork highlights the jungle and exoticness.

Catherwood drawing from Incidents of Travel. His artwork highlights the jungle and exoticness.

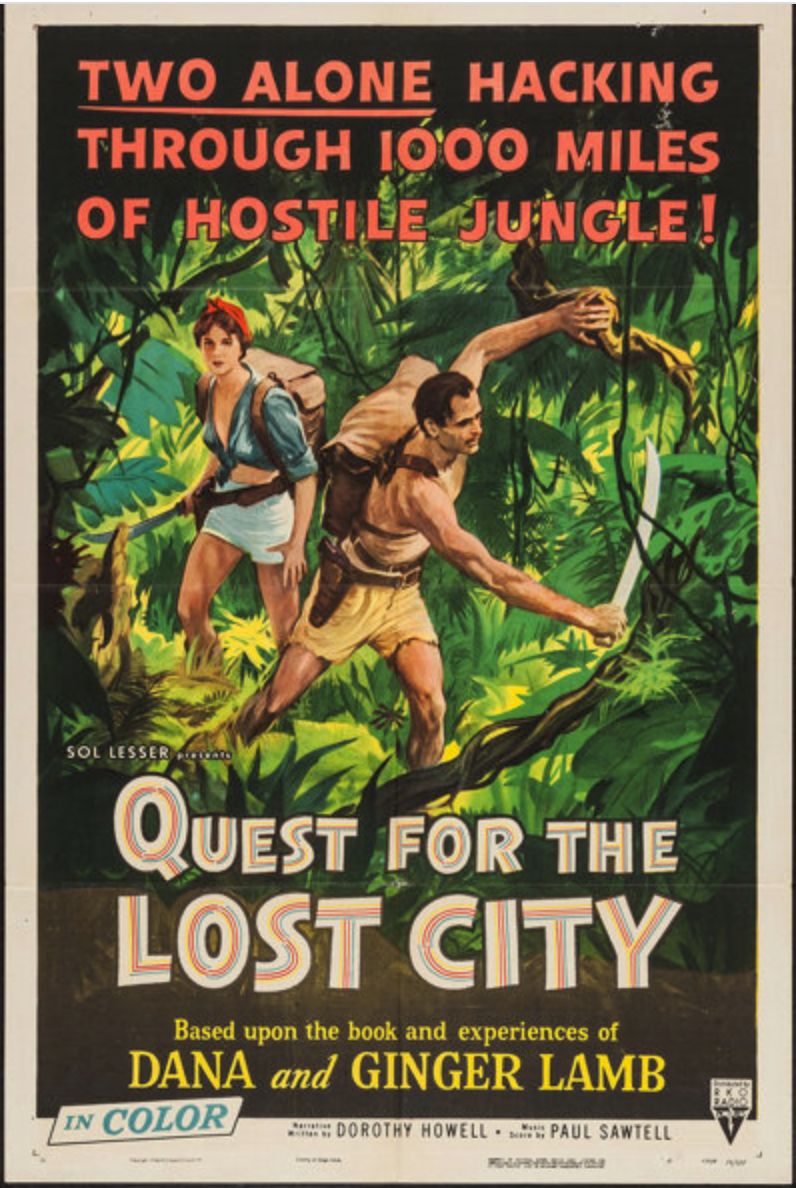

Movie poster for Dana and Ginger Lambs' documentary, Quest for the Lost City.

Movie poster for Dana and Ginger Lambs' documentary, Quest for the Lost City.

National Geographic is notorious for often using headlines claiming another "Lost City" has been found. Popularization of ideas based on the remoteness of a location causes for misconceptions about what the site was like pre-conquest

National Geographic is notorious for often using headlines claiming another "Lost City" has been found. Popularization of ideas based on the remoteness of a location causes for misconceptions about what the site was like pre-conquest

When John Lloyd Stephen’s first stumbled upon the city of Copan, he unknowingly created a tradition of exploration and archeology that many people would follow for years to come. This mindset of adventure and exoticness, the tantalizing tale of a Lost City, would inspire scholars (and pseudo-scholars) to propose a narrative rooted in misinterpretation.

This misconceived paradigm is rooted in ideas of ‘discovery’, framing analysis to come focusing on the 'lost and found' nature of discovery, illustrating sites as remote, isolated places with little connection to the outside world. By starting off with this idea of remoteness, scholars unknowingly trapped themselves to believe anything that came from these spaces, these grand cities, had only an abrupt beginning when they were discovered by them, the anglo-Saxon archeologist. They created an exotic fantasy rooted in adventure, in the discovery of the lost, that less academic participants would follow and misconstrue, having detrimental effects on the scholarly understandings of these spaces and the people who once inhabited them.

Intuitively, we recognize that these cities did not just appear out of thin air the moment these archaeologists stepped foot into the area (as much as fellows like aforementioned pseudo-scholars Dana and Ginger Lamb may want us to believe). These areas are rich with context and a rooted history that truthfully begins long before the archeologists and adventurers arrive. And yet if we look at these sites as only a sudden, merciful chance of fate and luck to bestow its sights, we can unintentionally inhibit and discredit the work of those who went to great lengths to create the site in its purposeful location. By transfixing to an idea of remoteness and isolation, we construct and contextualize only in modern day timelines. By claiming a city was lost and 'found' by archeologists, we implictly discredit the history it had before our arrival, creating divisive debates on greater issues, such as socio-political relations and commerce amongst the Maya.

Looking at the decades long debate of just how much inter-regional connectedness occurred between Mesoamerican cities can be directly related to the original ideas of ‘discovery’ in early Maya archeology. By focusing on the grand, obscure nature of the modern-day sites, we have created a narrative that only dwells on the remoteness of our current timeliner. In a similar way that the ideas of Peaceful Mayas was held dominant (without sound evidence), we may grasp onto ideas of remoteness, and transpose this to our analysis of artifacts and archeological records.

Dr. James Doyle, Assistant Curator at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Dumbarton Oaks junior fellow Alejandra Roche Recinos discuss how ideas of remoteness and exoticness can implicate findings in the field.

Dr. James Doyle, Assistant Curator at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Dumbarton Oaks junior fellow Alejandra Roche Recinos discuss how ideas of remoteness and exoticness can implicate findings in the field.

Webster notes that remoteness garnered the focus of the work rather than the realization that structurally, these cities were not isolated places but formerly bustling centers. With archeologists' transfixion on inaccessibility and isolation of these sites, it left to wonder how astutely we analyzed ceramics and artifacts found at a site. Were they immediately grouped in with the rest of the site's artifacts, explained only as a city’s abundance of resources? Or were we more astute and keenly aware of the materials and the environment, ready to argue against the likelihood of a vase being native to the area just because it was found at the site?

In short, ideas like remoteness, exoticness, and adventure surely had an influence in the early work of Mayanists. Thus, it leaves to question whether again the voice of the Maya was heard or ignored, as to a direct account from the people who experienced the quotations at hand the surely would elucidate information further. Although decades of debate exist as to how connected cities might have been, recent efforts have vouch more for the voice of the Maya and credit their inter-regional connections. From isotopic deposits in vases found between two cities to an immense outpour of excitement of discovery of the Balamku caves, archeologist in more modern times are eager to prove that despite the original explorers fascination with the remoteness of sites, these sites when appropriately re-contextualized to their accurate timelines reveal useful information about socio-political relationship and commercial establishments between ‘distant’, ‘isolated’ cities.

Apart from the critical need to understand the context of a site and its artifacts, by abiding by the normative fascination of the exotic, lone remoteness of these cities, scholars can create an explicitly exclusionary narrative. This narrative frames discovery and contribution solely from anglo-Saxon source, rather than one that recognizes that scholars simply pick up where the original writers left off. Highlighting ‘discovery’ creates a corrupted ‘new beginning’ of Maya civilization, implying that these sites only existed once a white audience stumbled upon them. In reality, the work of early scholars like Stephens and Catherwood is the continuation of a richly developed story, not an absolute new beginning. These sites have a history long before them, and a history that goes beyond them as well.

The Forgotten Maya

If you ask any average person what happened to the Maya the widely accepted answer is that the Maya were erased, their civilization perished and only monuments are left to echo what was once their former glory. It's surprising to many scholars that the Maya actually live on, with descendants hailing all across lower Mexico and into Honduras. And depending on who you ask, Maya live on in the cities too, from Los Angeles to Chicago, from fluent K’iche’ speakers to detribalized youths.

However in archeology, an institution that was used to present the “facts” of this civilization, often erased these descendants from the narrative. From Stephens to Morley to even modern Mayanist’s, all can be guilty of fostering a narrative of knowledge that not only erased the modern Maya, but also excluded these descendants from knowledge creation. Many times, discovery was framed in only the context of the archeologist, and the local people who usually led these explorers to the feet of the site were forgotten and never mentioned in the research papers. Although it may seem like a purely sympathetic, emotional consideration, the exclusion and erasure of the modern descendants created an incorrect framework in which Maya academia and findings were not fully contextualized and thus, not fully understood. The fact that Maya lived on was a crucial piece if the puzzle that would help understand the field further, and the sub par framework could have been avoided if early archeologist and analysts had given more weight to the voice of the descendants they found in archeological artifacts.

Lineage Altar Q found at the site of Copan. Lineage altars, or 'amanacer' altars showed the alliances and lineages of a city. The current king at the time of its construction would be seated facing the founding king, as if in discussion.

Lineage Altar Q found at the site of Copan. Lineage altars, or 'amanacer' altars showed the alliances and lineages of a city. The current king at the time of its construction would be seated facing the founding king, as if in discussion.

When artifacts like the Altar Q of Copan were first discovered, the lineage it depicted on its sides was assumed to be a deceased dynasty. Although these noblemen reigned for long expanses of time in ‘ancient’ accounts, artifacts like these were often misinterpreted as being the last page of a book, in which the main characters were long gone and no one left to consult for its fate.

Stephens writes of stumbling into Copan for the first time “the city was desolate. No remnant of this race hangs round the ruins, with traditions handed down from father to son and from generation to generation… none to tell whence she came, to whom she belonged, or what caused her destruction...all was mystery, impenetrable mystery…”. Although it may seem like a rational explanation, that a civilization has ended because no one from their original civilization lives in modern times, we realize that this was actually an inexcusably wrong judgement.

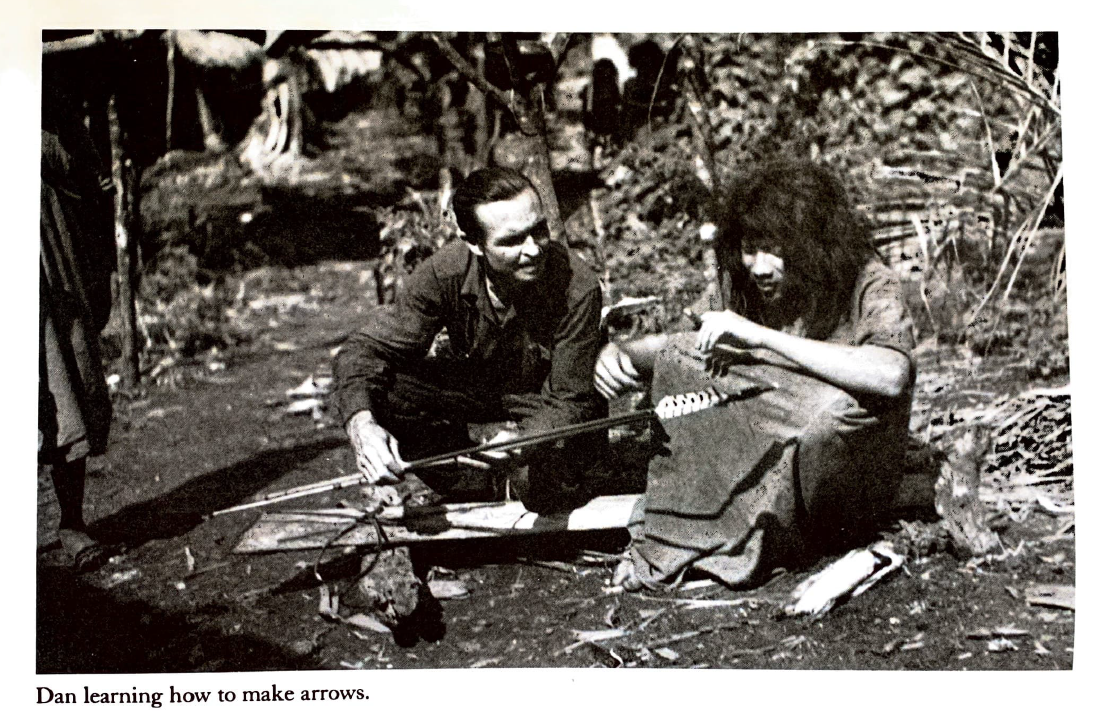

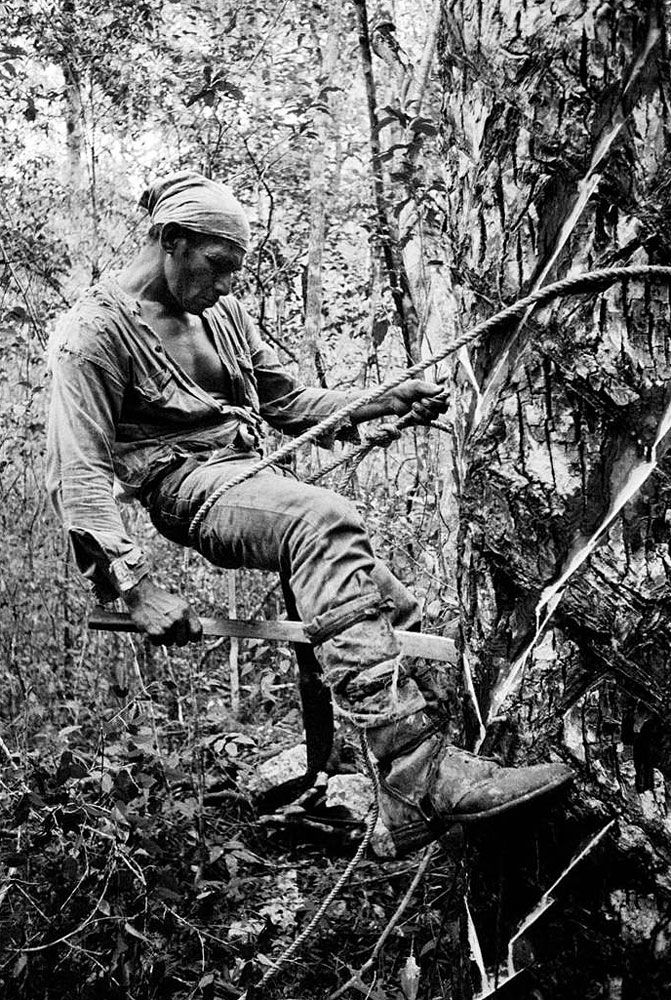

Throughout their documentary, the Lambs play the principle actors, teaching the Lacandon Maya how to make weapons. In reality their book explores how the Lacandon provided indispensable shelter and skill to them. Their documentary also erases the help of locals, most notably their right hand man Pancho.

Throughout their documentary, the Lambs play the principle actors, teaching the Lacandon Maya how to make weapons. In reality their book explores how the Lacandon provided indispensable shelter and skill to them. Their documentary also erases the help of locals, most notably their right hand man Pancho.

The very fact many Maya sites were discovered was thanks to the local rural men and women who would lead these explorers to these “ruins”. Stephens himself was lead to Copan at the hand of the locals, and attempted to purchase the land, which had been part of the community for years. Explorers Dana and Ginger Lamb were lead and guided by local Lacandan Maya, and yet their gaudy documentary credits them only as docile ‘savages’ who were unfamiliar with the magnitude and implications of the sites that surrounded them.

"For every archeologist who claims the first glimpse of this or that site, there is a Maya or humble logger or chiclero who knew of it long before."

This mentality that 1) Maya Civilization was long gone and 2) Modern locals were far removed form this history of ‘ancient’ Maya caused an incomplete narrative in academia that directly erased modern descendants and actors from their own story. In short, the biases of early archeologist in assuming locals held the sites in no importance and in no relation led them to ignore the very obvious connection between prehispanic Maya and their contemporary descendants.

Guatemalan archeologist and doctoral student at Brown, Alejandra Roche Recinos imparts some words about biased misconceptions she has experienced in the field and in life.

Guatemalan archeologist and doctoral student at Brown, Alejandra Roche Recinos imparts some words about biased misconceptions she has experienced in the field and in life.

It’s hard to argue that we had no idea these people lived on, even directly after the Spanish conquest and massacre of many indigenous communities we see the survival of native voice through map making, rituals, and language. To assume and perpetrate a story that they don’t exist is harmful for scholarly purposes, as it shifts all findings and understandings to be contextualized in a time “of the past” and of which guards us from re-examining our conclusions to see if they are accurate with the consideration of Maya’s modern people and history.

By eradicating a civilization that still lives on, we can harbor our biases and place blame on the distance from our current timeline for our misinterpretations, rather than confronting the reality that we have failed its modern descendants in creating an complete, accountable, respectable body of knowledge.

Chichicastenango market, Guatemala. Chichicastenango is one of the more world-renowned cities of modern Maya.

Chichicastenango market, Guatemala. Chichicastenango is one of the more world-renowned cities of modern Maya.

Lacandan Maya are one of the most notable descendants of their prehispanic ancestors. Maya lineage is complex, but some use language and geography to trace their roots.

Lacandan Maya are one of the most notable descendants of their prehispanic ancestors. Maya lineage is complex, but some use language and geography to trace their roots.

Photograph of a Mexican chiclero, cutting into rubber gum tree for its sap. Copyright Macduff Everton.

Photograph of a Mexican chiclero, cutting into rubber gum tree for its sap. Copyright Macduff Everton.

Modern day ritual conducted by a shaman. Many archeological sites are used by their living descendants for holy days and rituals.

Modern day ritual conducted by a shaman. Many archeological sites are used by their living descendants for holy days and rituals.

C O N C L U S I O N

The future of the Maya archeology field lies in holding our analysis and conclusion to a critical lens, and asking ourselves if we have done our best efforts to break away from common misconceptions. In acknowledging our bias and errors, we can hope to create a more holistic and accurate body of knowledge.

Temple of the Warriors. Chichen Itza, Mexico. Despite obvious evidence of war, early Mayanists concluded that Maya were a peaceful, docile people.

WORKS CITED

Webster, David. “The Mystique of the Ancient Maya,” in Archaeological Fantasies: How Pseudoarchaeology Misrepresents the Past and Misleads the Public. G.G. Fagan, (London and New York: Routledge, 2006)

Morley, S.G. The Ancient Maya. Palo Alto, California. Stanford Press. 1946

Black, Stephen L. “The Carnegie Uaxactun Project and the Development of Maya Archaeology,” Ancient Mesoamerica 1, no. 2 (1990)

Kinoshita, June. "Maya Art for the Record." Scientific American vol. 263. 1990.

John Lloyd Stephens, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan, Volume 1, (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1845)

IMAGES USED

Bonampak Muralshttp://www.latinamericanstudies.org/bonampak-2.htm

Palenque Image https://www.pinterest.com/pin/838302918109640604/

Incense Burnerhttps://luna.lib.uchicago.edu/luna/servlet/detail/uofclibmgr~16~ 16~1468786~1256463:unknown#

Map Headerhttps://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1671_Montanus_ Yucatan_map.png

Copan Jungle https://www.steppestravel.com/destinations/central-america/honduras/

Quest for the Lost City Movie Posterhttps://movieposters.ha.com/itm/movie-posters/documentary/quest-for-the-lost-city-rko-1954-one-sheet-27-x-41-documentary/a/161307-54375.s

Calakmul Junglehttps://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/09/maya-empire-snake-kings-dynasty-mesoamerica/

Calakmul Mural . http://www.mesoweb.com/articles/Martin2012.pdf

Altar Q of Copan . https://www.peabody.harvard.edu/node /2546

Chichicastenango Market http://americasonastroller.com/en/chichicastenango-market/

Dana Lamb & Lacandon Maya "The Fury of the Gods," in Quest for the Lost City: A True Life Adventure (Santa Barbara: Santa Barbara Press, 1984)

Maya Man in Ritual Banner https://alltournative.com/blogs/news/chaa-chaak-maya-ceremony/

Maya Ritual Ceremony https://www.pinterest.com/pin/265430971759704227/

Chichen Itza Temple of the Warriors https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/LESSING_ART_10312644545