Making the Maya World

Course Syllabus, Autumn 2020

Introduction

What is known today about the ancient Maya? Pyramids, palaces, and temples are found from Mexico to Honduras, texts in hieroglyphic script record the histories of kings and queens who ruled those cities, and painted murals, carved stone stelae, and ceramic vessels provide a glimpse of complex geopolitical dynamics and social hierarchies. Decades of archaeological research have expanded that view beyond the rulers and elites to explore the daily lives of the Maya people, networks of trade and market exchange, and agricultural and ritual practices. Present-day Maya communities attest to the dynamism and vitality of languages and traditions, often entangled in the politics of archaeological heritage and tourism. This course is a wide-ranging exploration of ancient Maya civilization and of the various ways archaeologists, anthropologists, linguists, historians, and indigenous communities have examined and manipulated the Maya past. From the thrill of decipherment to painstaking and technical artifact studies, from tropes of long-hidden mysteries rescued from the jungle to New Age appropriations of pre-Columbian rituals, we will examine how models drawn from astrology, ethnography, classical archaeology and philology, political science, and popular culture have shaped current understandings of the ancient Maya world, and also how the Maya world has, at times, resisted easy appropriation and defied expectations.

Course Description

This course is meant as an introductory-level seminar and assumes no prior knowledge about the ancient Maya, archaeological methods or theories, or the history of research in the Maya region. We will explore those topics together, asking in tandem what archaeologists and others currently know about the past and how they have come to know it.

Each week of the seminar will revolve around a general theme (e.g., “Hidden Cities,” “Big Digs,” etc.), with additional structure provided by key questions that will guide our readings, viewings, discussions, and activities (both asynchronous and synchronous). By the end of the course, students will be familiar with many of the major developments, key players, and ongoing issues in Maya history and archaeology, as well as capable of critically evaluating the historical, social, and political factors that shape current understandings and investigations of the ancient Maya world. The final product for the course, a Shorthand “scrollytelling” webpage, will showcase those skills by presenting a case study from Maya archaeology that highlights the history of research, people involved, and questions and contestations alongside accepted facts about the past.

There are no texts that you are required to purchase for this course. All readings, videos, and images collections will be made available through Canvas, Google Drive, and each week's dedicated Shorthand webpage, either as PDFs or as links to online resources.

Expectations, Workload, and Course Policies

Students are expected to attend synchronous class meetings each week and to come to each session not only having completed all of the assigned readings, but also prepared to discuss them. Each meeting will be prefaced by an online, asynchronous discussion through a Canvas forum, in which students are expected to post a substantive and timely question and/or response. Students should be actively engaged in synchronous meetings and cameras should be turned on during those meetings. If you require any accommodations or exceptions to these expectations, please reach out to me directly as soon as possible. For further information about resources, accommodations, and required paperwork, visit the University of Chicago’s Disability Services Office website.

In total, students should plan to spend about 2-2.5 hours per week on synchronous course activities (always held during the scheduled class meeting time) and an additional 6-8 hours on asynchronous activities. Specifically, this course will have a reading load of about 100 pages per week (~3 hours reading time), usually accompanied by documentary video materials and/or photographic archives (~2 hours of viewing time). Each week’s materials will require additional reflection through participation in a Canvas discussion form (~30 minutes max. of writing time). The final project for the course, a Shorthand storytelling webpage on a topic of your choice, will be completed in several stages, most of which will be peer-reviewed/edited by your classmates (~1-1.5 hours on average per stage and ~1 hour max. of peer-reviewing time). In anticipation of invited speakers, students will prepare and circulate specific questions for our guests (~30 min. max of writing time).

Grading Scale

A (94% and above); A- (90-93%); B+ (87-89%); B (83-86%); B- (80-82%); C+ (77-79%); C (73-76%); C- (70-72%); D+ (67-69%); D (63-66%); D- (60-62%); F (below 60%)

Office Hours (10% of final grade)

I will be available for Zoom office hours on Mondays from 10am-12pm and on Thursdays from 1pm-3pm (CST). Students can make appointments for 15-minute or 30-minute blocks of time (or combinations of the two) using the scheduling program Calendly. If you cannot make any of the meeting blocks available, please write to me and we will find another time.

Two office hours sessions are required: an initial 15-minute meeting after our first class session (September 30-October 5) to introduce ourselves to one another and a 30-minute meeting during reading week (December 2-7) to discuss the rough draft of your Shorthand webpage.

Canvas Discussions/Questions for Invited Speakers (20% of final grade)

Each of our weekly meetings will be preceded by an online discussion. Student will post a response addressing the “Key Questions” outlined for each week in the Course Schedule (below). Responses should be posted by Tuesday at 12 PM CST (i.e., two hours before the week’s synchronous class meeting begins).

Responses should be around 250 words, written in straightforward language. These should not be summaries. Responses should be designed to foment fruitful discussion and debate, engage with both the specifics of the texts and broader weekly themes, and create dialogue among the week’s materials (i.e., do not comment only on one assigned text or video).

In anticipation of weeks in which our discussions will include invited speakers, there will be an additional Canvas forum where students will post specific, substantive questions for our guests. Those questions should also be posted by Tuesday at 12 PM CST before the class meeting for which the speaker(s) will join us.

Synchronous Breakout Group Activities (20% of final grade)

Many weeks will involve breakout group activities or discussions that you will complete during our synchronous class meetings with 1-2 classmates, some of which will include workshopping your Shorthand pages (see below). Breakout activities will not be graded beyond participation.

September 29: Quick-Fire Bibliographies

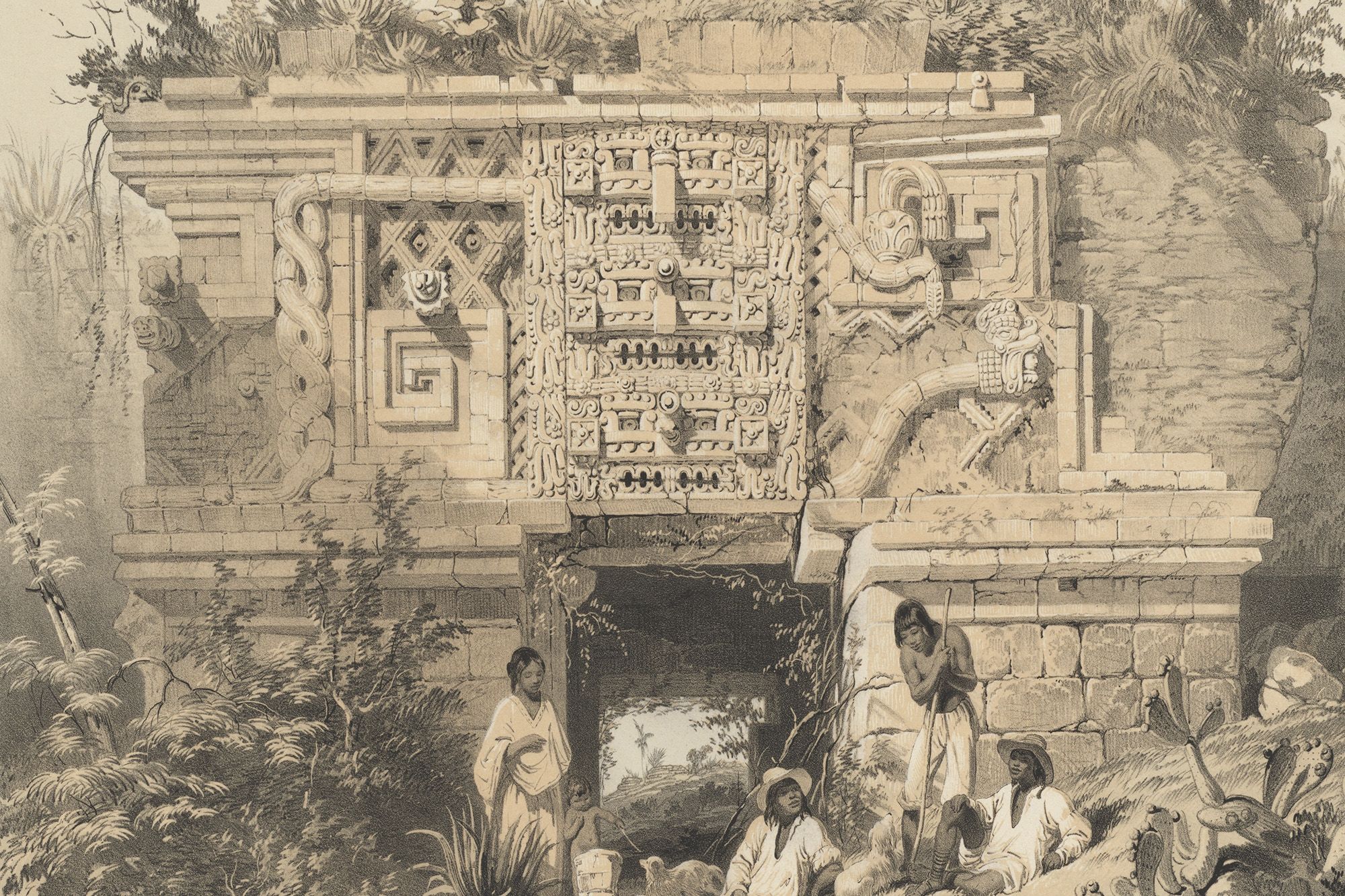

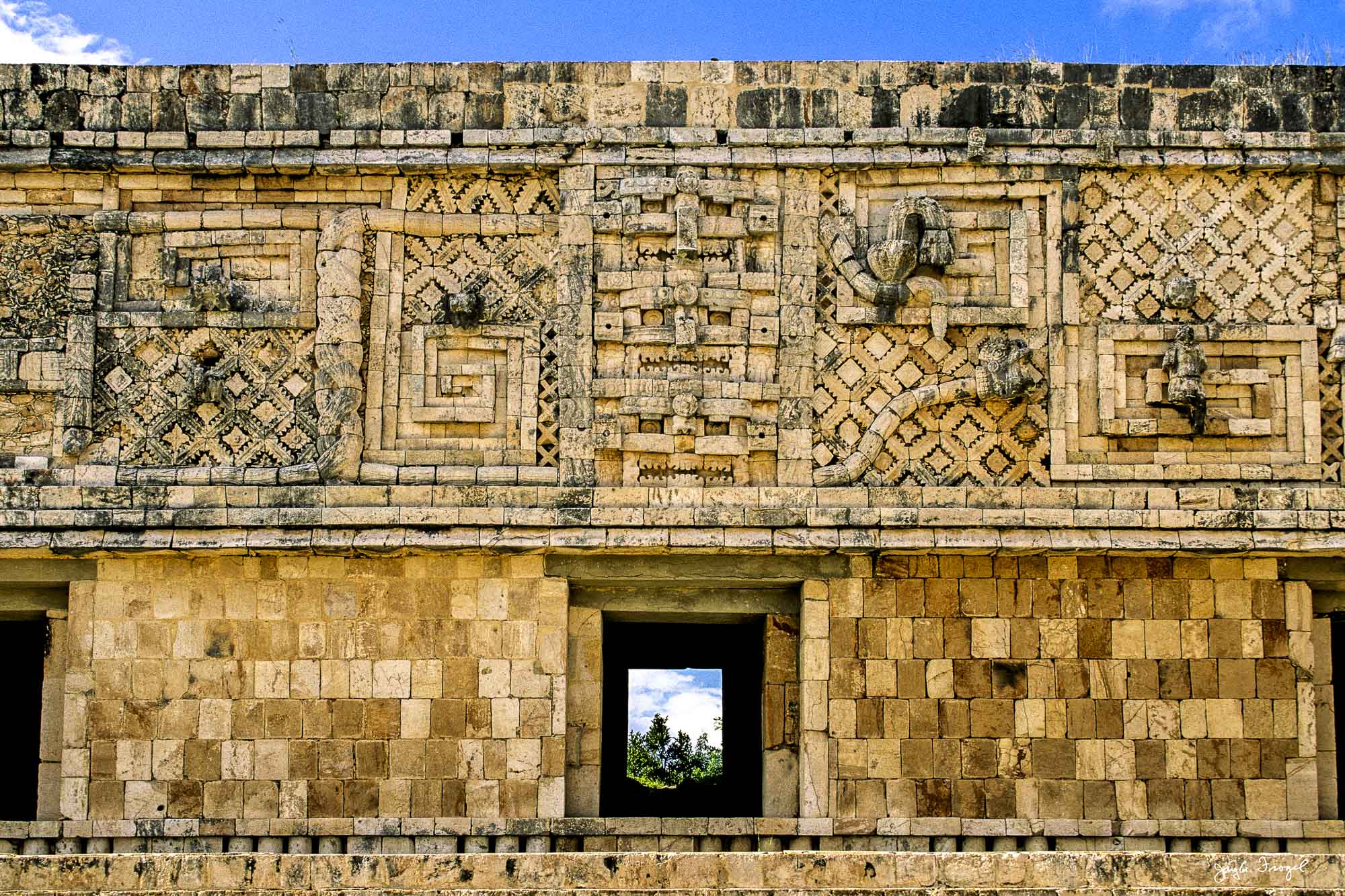

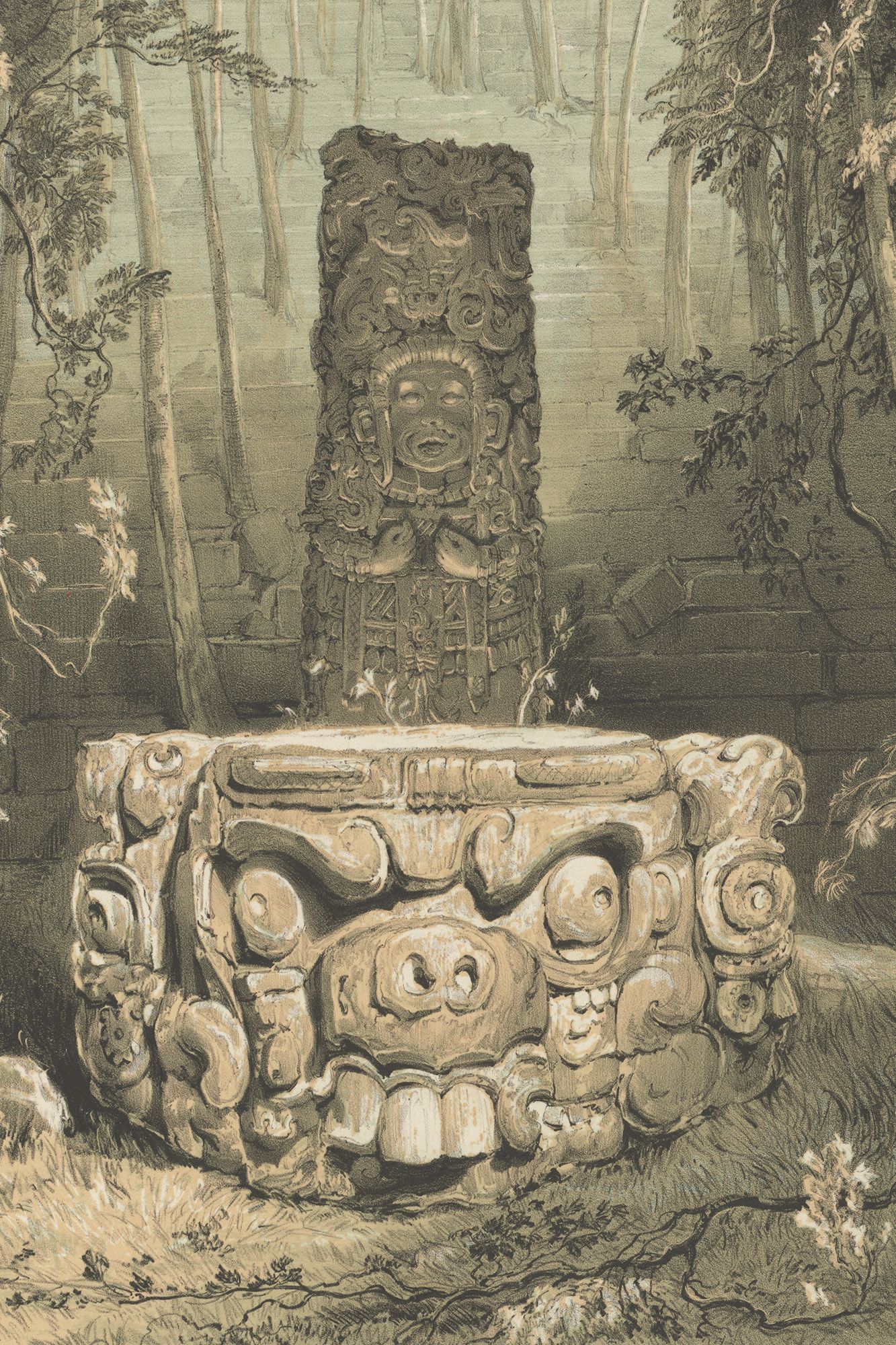

October 6: Maya Ruins and the Passage of Time - Jay Frogel and Frederick Catherwood

October 20: Maya in Unexpected Places

November 3: Digging the Glyphs

November 10: Shorthand Media/Outline Workshopping

November 17: The Maya at the Movies

Final Project (50% of final grade)

For the final project, each student will build a “scrollytelling” page on an approved topic of their choosing, using Shorthand. Shorthand is a digital storytelling platform used by a number of media outlets and institutions (e.g., BBC News, Sky News, the TODAY Show, UNICEF, the University of Cambridge, etc.), which has been made available to our course for free. “Scrollytelling” describes longform stories that incorporate audio, video, and animation effects that are triggered as a reader scrolls through the narrative. (This syllabus page is built using Shorthand).

Your Shorthand pages should explore the kinds of theories and themes discussed in this class, but in a particular context beyond the scope of the syllabus. For example, you might create a page that presents an “alternative” tour of a well-known archaeological site by focusing on the more recent history of research at the site rather than its ancient stories, detail the intellectual genealogies and social networks of a particular institution or excavation project, or provide a critical review of the history, influences, and impacts of specific New Age/pseudoarchaeological authors. Whatever your topic, your Shorthand page should showcase the knowledge that you gain throughout the quarter, but also contribute something new to the materials we will cover. Your Shorthand pages will not be made public, but may be shared within the university beyond our course (bear this in mind when considering your potential audience).

Shorthand pages will be built slowly over the course of the quarter and involve several stages of planning, drafting, and editing:

October 5, Existing Shorthand site review (10%): Choose a case study from the Shorthand website or Pinterest board and review the page, paying attention to the use of the platform’s features, the relationships between text and imagery, and the narrative structure. Be prepared to discuss your evaluation of the page during our synchronous class meeting on October 6.

October 12, Shorthand practice page (10%): Create a page about yourself to practice using the Shorthand editor (you may wish to view some Shorthand tutorials). Your page should include at least one of each of the following Shorthand sections: Text Over Media, Background Scrollmation, Reveal, and Media or Media Gallery.

October 26, Shorthand proposal (10%): Prepare a proposal (with the understanding that plans may change over the course of the quarter), that presents your topic of choice and a rough sketch of how you envision the narrative and media of your Shorthand page coming together. There is no specific length for the proposal, but it should address the following questions:

1. What question or issue does your story tackle? Why is it of interest to you and why would it be of interest to others?

2. Has this story been told before? If so, why does it merit retelling? If not, why not?

3. What resources do you have to tell this story? What bibliography, images, interview, or original data do you have at your disposal?

November 9, Shorthand media/outline (15%): Upload at least 1 map, 6 images, 1 video, and 1 animation to your Shorthand page in the general outline you envision for the final product (the text does not need to be finalized - you may leave Shorthand’s placeholder text).

November 24, Complete rough draft of Shorthand page (15%)

November 30, Peer edit of Shorthand page rough drafts (15%): Each student will read, evaluate, and comment on another’s draft (including the text, images, organization, etc.). Be prepared to workshop/discuss your own Shorthand pages and your edits during our synchronous class meeting on December 1.

December 8, Final Shorthand page (25%)

Extra Credit (2% of final grade)

During the first week of the quarter (October 1-4, 2020), the American Foreign Academic Research organization (AFAR) will be hosting the 14th annual “Maya at the Playa” conference. This year, the event will be held virtually, with all lectures and workshops taking place over Zoom. If you would like to earn extra credit, write a short review (c. 250 words) of one of the lectures, addressing the following questions:

1. Why did you choose the lecture that you attended? What captured your interest about the speaker or the topic?

2. What was the speaker’s main argument?

3. Did the speaker draw on earlier excavations, decipherments, theories, or other information/data in building his/her claims?

4. How did the speaker convey information during the lecture? Was it easy to follow, difficult to understand, surprising in certain ways?

Academic Honesty

Making references to the work of others strengthens your own work by granting you greater authority and by showing that you are part of a discussion located within an intellectual community. When you make references to the ideas of others, it is essential to provide proper attribution and citation. Failing to do so is considered academically dishonest, as is copying or paraphrasing someone else's work. Such offenses are punishable under the University’s disciplinary system. In general, any written or electronic source consulted (or any material used from that source, directly or indirectly), should be identified. If you are in doubt about what constitutes the “use” of a source, how proper citation should be done, or anything regarding academic honesty, please ask.

Course Schedule and Readings

September 29: Introduction

Personal introductions; course overview and requirements; review of themes and key questions

Asynchronous Activities:

Juan Luis Borges, “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” in Labyrinths: Selected Stories and Other Writings, eds. D.A. Yates and J.E. Irby, (New York: New Directions Books, 1962), 20-33.

Synchronous Activities:

Introduction and overview

Discussion of reading

Breakout groups: Quick-Fire Bibliographies

October 1-4: Maya at the Playa Conference

(Extra Credit)

October 6: Hidden Cities

How is Maya archaeology framed in terms of “discovery”? What are some of the ways in which the material culture, environments, and people encountered at Maya archaeological sites are described? How do narratives of discovery shape the questions that are asked (and who gets to ask them) about the Maya past and the way information is communicated to both scholarly and public audiences?

Asynchronous Activities:

Stephen D. Houston and Takeshi Inomata, “Introduction," in The Classic Maya (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 3-27.

John Lloyd Stephens, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan, Volume 1, (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1845), 101-105, 117-129, 134-158, 158-160.

Optional: Augustus Le Plongeon, “Preface,” in Queen Moó and the Egyptian Sphinx, (New York: Augustus Le Plongeon, 1900), vii-xxv.

Marcello Canuto et al., “Ancient lowland Maya complexity as revealed by airborne laser scanning of northern Guatemala.” Science 361(6409).

National Geographic, Lost Treasures of the Maya Snake Kings (2018).

Optional: Amanda Ruggeri, “In Guatemala, the Maya world untouched for centuries,” BBC Travel, 15 Sep 2020.

Canvas discussion forum

Synchronous Activities:

Discussion of weekly materials

Discussion of Shorthand reviews

Breakout groups: Maya Ruins and the Passage of Time - Jay Frogel and Frederick Catherwood

October 13: Big Digs

Who are some of the key people and institutions in the development of the discipline of Maya archaeology? How do intellectual genealogies (professors-students-partners-etc.) shape the practices, methodologies, and theories of Maya archaeology? What are some of the driving forces behind funding support for Maya research?

Asynchronous Activities:

Stephen L. Black, “The Carnegie Uaxactun Project and the Development of Maya Archaeology,” Ancient Mesoamerica 1, no. 2 (1990), 257-276.

Edwin Shook and Stephen D. Houston, “Recollections of a Carnegie Archaeologist,” Ancient Mesoamerica, 1, no. 2 (1990): 247-252.

Fox Movietone News, “Mecca of the Americas, Chichen Itza” (1931)

Optional: Franz Boas, "Scientists as Spies," The Nation 109, no. 2842 (1919).

William R. Fowler, Jr. and Stephen D. Houston, “Excavations at Tikal, Guatemala: The Work of William R. Coe,” The Latin American Anthropology Review 3, no. 2 (1991): 61-63.

Optional: Penn Museum, “Tikal Project - 1959 #1” (Scenes from the 1959 field season, including excavations in the Great Plaza).

Lizzie Wade, “The Believer: How a Mormon lawyer transformed Mesoamerican archaeology—and ended up losing his faith,” Science 359, no. 6373 (2018): 264-268.

VICE News, “Mayan Ruins in Guatemala Could Become a U.S.-Funded Tourist Attraction,” (2020)

Brown University "El Zotz masks yield insights into Maya beliefs," July 18, 2012.

Optional: Marshall Joseph Becker, “Priests, Peasants, and Ceremonial Centers: The Intellectual History of a Model,” in Maya Archaeology and Ethnohistory, ed. N. Hammond and G.R. Willey, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1979), 3-20.

Optional: Sarah E. Newman, “Rubbish, Reuse, and Ritual at the Ancient Maya Site of El Zotz, Guatemala,” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 26, no. 2 (2019): 806-843.

Canvas discussion forum

Questions for conversation with guest speaker

Synchronous Activities:

Discussion of weekly materials

Conversation with Stephen Houston (Brown University)

October 20: Inventing “the Maya”

Why and how did “the Maya” become an object for archaeological, historical, and ethnographic study? What are the ongoing effects and implications of pan-Mayanism, for both the past and the present?

Asynchronous Activities:

Les Mitchel, Maya are People (1951) – Part 2 Optional: Part 1

Victor D. Montejo, “Representation via Ethnography: Mapping the Maya Image in a Guatemalan Primary-School Social-Studies Textbook,” in Maya Intellectual Renaissance: Identity, Representation, and Leadership, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005), 37-60.

Laurie Kroshus Medina, "Commoditizing Culture: Tourism and Maya Identity," Annals of Tourism Research 30, no. 2 (2003): 353-368.

Mallory Matsumoto, “The Stela of Iximche’ in the Context of Linguistic Revitalization and Hieroglyphic Revival in Maya Communities of Guatemala,” Estudios de Cultura Maya 45 (2015): 225-258 (Spanish version).

“Xiimbal Kaaj,” Pat Boy and Yazmín Novelo

Optional: Quetzil E. Castañeda, "'We Are Not Indigenous!': An Introduction to the Maya Identity of Yucatan," The Journal of Latin American Anthropology 9, no. 1 (2004): 36-63.

Canvas discussion forum

Synchronous Activities:

Presentation by the UChicago Visual Resources Center

Discussion of weekly materials

Breakout groups: Maya in Unexpected Places

October 27: (Re)Making Maya Art

Of the many material remains of the ancient Maya past, which do scholars label “artifacts” and which do they label “art”? How do those labels affect the way material culture is studied, manipulated, conserved, or displayed? What visualization techniques (e.g., artistic reconstructions, 3D scanning, etc.) have facilitated the study of ancient Maya material culture? Traditionally, who is/has been responsible for those products? Should drawings, reconstructions, and scans be considered raw data or expert interpretations?

Asynchronous Activities:

Carolyn Dean, “The Trouble with (the Term) Art,” Art Journal 65, no. 2 (2006): 24-33.

Heather Hurst, Leonard Ashby, Mary Pohl, and Christopher L. von Nagy, “The Artistic Practice of Cave Painting at Oxtotitlán, Guerrero, Mexico,” in Murals of the Americas, ed. V.I. Lyall, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019), 15-42.

Optional: Heather Hurst, “Painting with Mittens and Bananas,” TEDx Skidmore College, 2013.

Mary F. McVicker, “Teopancaxco: The Art of Recording the Ruins,” “Chichén Itzá,” “Life Begins at Fifty,” “The Extraordinary Undertaking: The Murals in the Upper Temple of the Jaguars,” and “Color Plates,” in Adela Breton: A Victorian Artist Amid Mexico’s Ruins, (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2005), 33-44, 53-69, 91-106.

Adela Breton images in LUNA

Ian Graham, “Tatiana Proskouriakoff: 1909-1985,” American Antiquity 55, no. 1 (1990): 6-11.

Tatiana Proskouriakoff images in LUNA

Barbara W. Fash, “Beyond the Naked Eye: Multidimensionality of Sculpture in Archaeological Illustration,” in Past Presented: Archaeological Illustration and the Ancient Americas, ed. J. Pillsbury, (Washington, D.C., Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2012), 449-470.

Jago Cooper, “Preserving Maya Heritage with the British Museum,” Google Arts and Culture.

Canvas discussion forum

Questions for conversation with guest speaker

Synchronous Activities:

Discussion of weekly materials

Conversation with Heather Hurst (Skidmore College)

November 3: Reading Maya Writing

How and when was Maya writing deciphered? Did it happen suddenly or slowly? How did that process compare to the decipherment of other writing systems? How did decipherment change the interpretation of Maya history and material culture? What kinds of work come after decipherment?

Asynchronous Activities:

Nightfire Films, Breaking the Maya Code (2008)

Marc Zender, “Theory and Method in Maya Decipherment,” The PARI Journal 17, no. 2 (2017): 1-48.

Optional: Matthew C. Watson, “Staged Discovery and the Politics of Maya Hieroglyphic Things,” American Anthropologist 114, no. 2 (2012): 282-296.

Ian Graham, “The Corpus Program,” in The Road to Ruins (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2010), 337-348.

Optional: The Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions

Simon Martin and Nikolai Grube, Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens, 2nd ed., (London, Thames and Hudson, 2008): choose any chapter (requires UChicago login)

Stephen Houston and Simon Martin, “Through seeing stones: Maya epigraphy as a mature discipline,” Antiquity 90, no. 350 (2012): 443-455.

Maurice Pope, “Luvian Hieroglyphic” in The Story of Decipherment: From Egyptian Hieroglyphs to Maya Script, (London, Thames and Hudson, 1999), 136-145.

William Mullen, "Deciphering a Link to Past," Chicago Tribune, May 18, 1997.

The Oriental Institute, "Chicago Hittite Dictionary Project," 2010.

Canvas discussion forum

Questions for conversation with guest speakers

Synchronous Activities:

Discussion of weekly materials

Conversation with Theo van den Hout (University of Chicago) and Marc Zender (Tulane University)

Breakout groups: Digging the Glyphs

November 10: Lost and Found

What are the similarities and differences between the actions and interests of archaeologists, art collectors, and looters? Are archaeological research, the art market, and illicit looting connected? If so, how? If not, do they affect one another intellectually, economically, and/or ethically?

Asynchronous Activities:

Nightfire Films, Out of the Maya Tombs (2017)

James Doyle, “The Odyssey of Piedras Negras Stela 5,” in The Market for Mesoamerica: Reflections on the Sale of Pre-Columbian Antiquities, edited by C.G. Tremain and D. Yates, (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2019), 87-111.

Dana Lamb, Quest for the Lost City (1954)

Dana Lamb and Ginger Lamb, "The Fury of the Gods," in Quest for the Lost City: A True Life Adventure (Santa Barbara: Santa Barbara Press, 1984), 324-340.

Andrew Scherer, Charles Golden, Stephen Houston, and James Doyle, “A Universe in a Maya Lintel I: The Lamb’s Journey and the ‘Lost City’,” Maya Decipherment, 25 Aug 2017.

Optional: Julie Huffman-Klinkowitz and Jerome Klinkowitz, “Quest for the Lost City”, in The Enchanted Quest of Dana and Ginger Lamb, (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2006), 135-171.

Canvas discussion forum

Questions for conversation with guest speaker

Synchronous Activities:

Discussion of weekly materials

Conversation with James Doyle (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Breakout groups: Shorthand Media/Outline Workshopping

November 17: Maya Modernism and the Popular Past

How have perceptions of the ancient Maya past been shaped by the present in which that past was conceived? How have the Maya been transformed and incorporated into popular culture? What kinds of social and political factors influence which theories about the past are considered acceptable or dismissed?

Asynchronous Activities:

David Webster, “The Mystique of the Ancient Maya,” in Archaeological Fantasies: How Pseudoarchaeology Misrepresents the Past and Misleads the Public, ed. G.G. Fagan, (London and New York: Routledge, 2006), 129-153.

Jesse Lerner, “A Fevered Dream of Maya: Robert Stacy-Judd,” Cabinet, 2001

Quetzil Castañeda, “Vernal Return and Cosmos: That Serpent on the Balustrade and the New Age Invasion,” in In the Museum of Maya Culture: Touring Chichén Itzá, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 175-200.

“The Descent of Kukulkán,” Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian

David Stuart, "Q & A about 2012" and podcast from The Academic Minute

Leandro Katz, Paradox, (2001)

Optional: Jesse Lerner, "The Paradoxes of Quiriguá," Journal of Film and Video 57, no. 1-2 (2005): 78-83.

Pete Wells, "Why I'm Not Reviewing Noma Mexico," New York Times, May 23, 2017.

Optional: "Rosalia Chay Chuc," Chef's Table BBQ, Netflix, 2019

Canvas discussion forum

Synchronous Activities:

Discussion of weekly materials

Breakout groups: The Maya at the Movies

November 24: Thanksgiving/Study Week NO CLASS

December 1: The Futures of the Maya Past

Does the history of Maya archaeology look different when written from Guatemala rather than North America? What role has and does Guatemalan nationalism play in interest in the ancient Maya past? How have the roles for Guatemalan archaeologists, women, and indigenous people in Maya archaeology changed over the past century? How might (or should) they continue to change?

Asynchronous Activities:

Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos, “Archaeology in Guatemala: Nationalist, Colonialist, Imperialist,” in The Oxford Handbook of Mesoamerican Archaeology, ed. D.L. Nichols and C.A. Pool, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 55-68.

Jessica MacLellan, Melissa Burnham, and María Belén Méndez Bauer, "Community Engagement around the Maya Archaeological Site of Ceibal, Guatemala," Heritage, 3 (2020): 637-648.

Iyaxel Ixkan Anastasia Cojtí Ren, "The Experience of a Mayan Student," in Being and Becoming Indigenous Archaeologists, ed. G.P. Nicholas, (London and New York: Routledge), 84-92.

Optional: Bárbara Arroyo, "Juan Pedro Laporte (1945-2010)," Journal de la Sociéte des américanistes, 96, no. 2 (2010): 293-296 (in Spanish).

Optional: Pia Flores, "Dos arqueólogas: Nuestro trabajo es más que lo que salió en NatGeo (y no es para el turismo)," Nomada: February 28, 2018.

Canvas discussion forum

Questions for guest speakers

Synchronous Activities:

Discussion of weekly materials

Conversation with Alejandra Roche Recinos (Brown University) and Jessica MacLellan (University of California, Los Angeles)

Breakout groups: Peer edits of complete Shorthand drafts