Maya Roads

Exploring Agency, Thought, and Social Organization

The arrow indicates the intersection at which Sacbé 15 meets Sacbé 5 (diagram of the image on the title page). Source: https://luna.lib.uchicago.edu/luna/servlet/detail/uofclibmgr~16~16~1462184~1241722:unknown?qvq=q:sacb%C3%A9&mi=2&trs=83#

The arrow indicates the intersection at which Sacbé 15 meets Sacbé 5 (diagram of the image on the title page). Source: https://luna.lib.uchicago.edu/luna/servlet/detail/uofclibmgr~16~16~1462184~1241722:unknown?qvq=q:sacb%C3%A9&mi=2&trs=83#

Why are roads important as a topic of study?

During my years as an elementary, middle, and high school student, aside from the famous Silk Road, I never really learned about roads. They weren’t talked about in class and I rarely saw them in museum galleries or exhibits. They weren't glamorous or flashy and I would guess that most people don’t find roads all that interesting.

Connecting disparate regions and settlements but never really factoring in to discussions of the civilizations themselves, roads are often thought of (if at all) as simply passageways of movement that facilitate communication, trade, and commerce. Even my studies of the Silk Road only really amounted to this, with the occasional reading about bandits or thieves that operated in the remote regions of the Silk Road. Although roads do in fact facilitate all of these things, they are much more than just spaces through which people pass. For one, there are roads and causeways that connect settlements (inter-site), as well as streets and avenues within settlements (intra-site), facilitating micro-movements and social life.

In this Shorthand page, I will focus on Maya roads. After a brief overview of the different types of Maya roads, I want to talk about what these roads can tell us about the Maya, according to scholars in Maya archaeology such as Dr. Scott Hutson and Jacob Welch, Dr. Timothy Pugh, and Dr. Angela H. Keller.

By examining Maya roads, we can learn about:

- The relationships of power among various Maya settlements (some larger and more influential and others smaller and less influential) and how agency is exercised and demonstrated

- How the Maya thought about roads (by analyzing Mayan languages)

- The negotiation of public and private life in Maya settlements and how societal organization changed over time

Lastly, I will briefly discuss technologies such as LiDAR that have the potential to advance research on this topic into the future.

In this way, studying roads provides us with a holistic approach to the field of Maya archaeology, one in which we recognize and pay attention to the interconnected links between different elements of society, all of which contribute to our understanding of the civilization at large.

Sacbé in Labná, Yucatan. Source: https://luna.lib.uchicago.edu/luna/servlet/detail/uofclibmgr~16~16~1464105~1246839:unknown?qvq=q:sacb%C3%A9&mi=0&trs=83#

General Overview of Maya Roads

The Mayan word “sacbeob” (singular: “sacbé”) refers to formal roads or causeways (Pugh). Meaning “white roads,” sacbeob were straight and often raised up from the ground, with parapets lining the sides (Pugh). Sometimes, they were constructed in wet, swampy areas, allowing people to pass through on foot (Hutson and Welch, 422). Famous for not having vehicles or draft animals like horses to help transport goods, the Maya built these sacbeob to serve as pedestrian walkways (Pugh). Additionally, because of their raised nature, sacbeob were sometimes used to manipulate and divert surface water (Pugh). These pathways facilitated enhanced communication and the flow of economic goods. Therefore, they were important public spaces, fostering social unity, demonstrating political power, and marking boundaries (Hutson and Welch, 422) (Pugh). These large causeways were constructed to connect distant settlements, an example of which is the Tzacauil sacbé, east of Yaxuna, Yucatán. This is an example of inter-site communication (Hutson, Magnoni, and Stanton, "'All that is solid…': Sacbés, Settlement and Semiotics at Tzacauil, Yucatán").

Streets and avenues, on the other hand, are passageways that can be found within settlements (the use of the words “street” and “avenue” are used by academics to refer to these structures for the sake of simplicity and organization) (Pugh). As public spaces, they often led to public plazas where social activities were held (Pugh).

An important thing to note about these roads is that they were intentionally constructed (Hutson and Welch, 434). They were not merely clearings that naturally appeared over time, but rather objects designed with specific intentions and purposes in mind (Hutson and Welch, 434).

Now that we’ve covered the context necessary to think more deeply about roads and the function of roads in and between Maya settlements, let’s dive into our main question: What can roads tell us about the Maya?

Image on the left: Sacbé at Dzibilchaltun, Yucatán. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacbe

Power and Agency

“Sacred Landscapes and Building Practices at Ucí, Kancab, and Ucanha, Yucatán, Mexico"

Dr. Scott R. Hutson and Jacob A. Welch

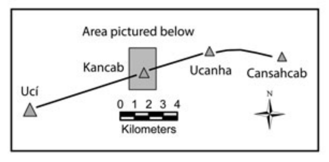

In “Sacred Landscapes and Building Practices at Ucí, Kancab, and Ucanha, Yucatán, Mexico,” Dr. Scott R. Hutson and Jacob A. Welch write about broad stone causeways that connect the larger settlement of Ucí to the smaller settlements of Kancab and Ucanha. Compared to Kancab and Ucanha, Ucí has both the largest ceremonial center and the largest population and therefore, the most resources (421).

Visualization of the causeways connecting Ucí, Kancab, and Ucanha. Source: Hutson and Welch, 424

Visualization of the causeways connecting Ucí, Kancab, and Ucanha. Source: Hutson and Welch, 424

I wanted to bring in this piece to demonstrate the power and agency that Kancab and Ucanha exercised, despite being dwarfed by Ucí.

When constructing sacred landscapes, Ucí took advantage of exceptional natural features in the form of large depressions with wet caves (431). These hidden caves served as portals through which they could communicate with supernatural beings (431). They were sacred locations at which rituals processions took place (431).

Although they also had access to similar natural features, Kancab and Ucanha built causeways and ceremonial compounds for their religious proceedings instead (431).

“The most common explanation of the function of these kinds of causeways is that they hosted ritual processions. Ringle (1999) argues that in the Late Preclassic period, these processions helped integrate communities by linking the core with outliers while at the same time legitimating the authority of the community’s leaders.”

The causeways, in particular, were arranged in accordance with the cardinal directions, symbolizing a connection to spiritual beings (431). In this way, Kancab and Ucanha, smaller settlements with fewer resources and less power compared to Ucí, found other ways to construct their own sacred landscapes in the form of causeways (431). By negotiating their own forms of power and agency, Kancab and Ucanha were both able to influence the course of history.

“Nevertheless, the site layouts at Ucanha and Kancab speak to more basic notions of power; carrying out an intentional plan that makes the community socially and ritually viable through the reproduction of cosmological structures."

“Though Uci was much larger than Kancab and Ucanha and subsumed these sites by linking to them with an intersite causeway, the people at Kancab and Ucanha managed to maintain a degree of ritual autonomy."

Therefore, by looking at the causeways through which Kancab and Ucanha exercised their agency, we are able to glean information about the ways in which social organization was negotiated among settlements of differing power and influence.

Image on the right: Sacbé 1, Chichén Itzá, view from the north. Source: https://luna.lib.uchicago.edu/luna/servlet/detail/uofclibmgr~16~16~1462408~1241985:unknown?qvq=q:sacb%C3%A9&mi=3&trs=83#

Language and Thought

“A Road by Any Other Name: Trails, Paths, and Roads in Maya Language and Thought"

Dr. Angela H. Keller

When we hear the word “road,” we conjure up specific impressions in our minds, perspectives that inform our understanding of what roads are used for and what they mean to us. Therefore, I would like to look at Mayan words related to roads. Although it is not the same as studying roads directly, a foray into roads through a linguistic lens will be fruitful for thinking about the interactions between language and the built landscape.

In “A Road by Any Other Name: Trails, Paths, and Roads in Maya Language and Thought,” Dr. Angela H. Keller studies the context and meaning of the Mayan word for "road."

The closest English approximation of the word “road” is “beh,” the same “be” that is in “sacbé.” However, this is merely an approximation, as according to Keller, “within the word beh is the unfolding of life, destiny, obligation, transformation, order, and a conduit to the supernatural, all bound to unending cycles of time” (14). This connotation (that does not exist in the English word for “road”) is crucial for understanding the importance of roads in Mayan language and thought. In this sense, “life is a road,” with the sentence “k in tz’ookl in bel” roughly transliterated as “I finish my road” or “I marry" (14). The meaning of the word “beh” has changed little over time, only losing the connotation of work during the transition into modern times (14). Regardless, there is something important here: the conflation of roads and time (14). Walking down a road is akin to time passing; the past is behind and the future is forward (14). By looking at roads (“beh”) through linguistic analysis, we can gain a better understanding of Maya life and thought.

Image on the left: Sacred Cenote, Chichén Itzá, view from the north with Sacbé 1 leading towards the ceremonial center. Source: https://luna.lib.uchicago.edu/luna/servlet/detail/uofclibmgr~16~16~1462409~1241984:unknown#

Social Organization

“From the Streets: Public and Private Space in an Early Maya City"

Dr. Timothy W. Pugh

Although I’ve written a lot about monumental architecture such as major causeways connecting disparate settlements (inter-site communication), I now want to turn your attention to passageways within settlements (intra-site movement). That is, streets, avenues, and paths and how these public spaces that demarcate the public and private spheres can be analyzed to glean more information about the culture of social organization in early Maya settlements.

In “From the Streets: Public and Private Space in an Early Maya City,” Dr. Timothy W. Pugh details the tensions inherent in negotiating public and private spaces in the lowland Maya site of Nixtun-Ch’ich’ in modern-day Guatemala.

Pugh writes about the distinction between cooperatively and competitively organized societies:

“Cooperative and competitive societies define a continuum between societies that invest heavily in public goods and greater legibility (cooperative) and societies with few of these amenities and often with more dispersed layouts and greater segmentation (competitive)."

Additionally, while cooperative societies oftentimes don’t have one figure to represent them as their leader, competitive societies do, with that central figure serving as a conduit between the people and supernatural beings.

Streets and avenues (for Pugh’s purposes, he designates streets as east-west corridors and avenues as north-south ones) are decidedly public spaces that coexist alongside residential or private spaces. This tension between the public and private domains exists in the form of people like street vendors and performers, as well as political activists, who use public spaces for their own purposes (economic or otherwise).

Pugh writes that since cooperative societies invest heavily in public spaces, in these societies, streets and avenues are wider and so are the public plazas that they connect to (public plazas are where lots of activities such as street vending and performances take place). This is so that these public spaces can accommodate these people and their activities.

In contrast, competitive societies that have fewer resources in the first place have narrower streets and avenues, private spaces swallowing up what was formerly public domain.

Pugh writes that from the Middle (800-400/300 BC) to Late Preclassic Period (400/300 BC-AD 200), many of these settlements in the Maya lowlands exhibited a transition from wider to narrower streets and avenues. In consequence, Pugh argues that this is evidence of a society that has transitioned from being a more cooperative one to being one that is more competitive.

Therefore, by looking at roads on a small scale, we are able to discern meaningful information about the social organization of early Maya settlements. What could have brought about such a transition has not yet been addressed, which can be a point of further research for Maya archaeologists to come.

First Image: Structure 22A, Copán, exterior view. Structure 22A is believed to be a "Mat House" (popol naah), a meeting place for nobles. Source: https://luna.lib.uchicago.edu/luna/servlet/detail/uofclibmgr~16~16~1278253~301743:unknown?qvq=w4s:/what%2FCourts%2Band%2Bcourtiers%2Fwhere%2FMaya%2F&mi=1&trs=57

Second Image: Initial Series Group, Chichén Itzá, Stairway between the Palace of Phalluses and the House of the Snails. Source: https://luna.lib.uchicago.edu/luna/servlet/detail/uofclibmgr~16~16~1462529~1243279:unknown#

LiDAR Technology

The Future of Roads in Maya Archaeology

"LiDAR, which stands for Light Detection and Ranging, is a remote sensing method that uses light in the form of a pulsed laser to measure ranges (variable distances) to the Earth"

In essence, LiDAR can be used to examine the surface of the earth.

Understandably, this technology is invaluable to Maya archaeologists, helping them identify regions for further research and excavation, especially in areas that are difficult to access.

For road networks in particular, LiDAR has the potential to assist Maya archaeologists in mapping out long-distance causeways, many of which point to how separate (and disparate) Maya settlements communicated with one another. Learn more about this in the video below!

Conclusion

Although roads are often overlooked in research on ancient civilizations, they are important for being able to further advance our knowledge. In the case of the Maya, by looking at and analyzing roads, we can glean information about agency and power relationships among Maya settlements, Maya life and thought about movement and time, and the changing climate of social organization within Maya settlements. Looking to the future, emergent technologies like LiDAR have the potential to continue to shape research in this subject area.

Want to Learn More?

Access the research papers and articles I referenced throughout this Shorthand page by clicking on the corresponding buttons below (organized by section and author's last name)

Note: Pugh's article does not include page numbers, which explains the lack of page number citation for this paper throughout the entire Shorthand page

Any other sources will have direct links embedded in the text

All images are accompanied by links to their sources