November 17: Maya Modernism and the Popular Past

How have perceptions of the ancient Maya past been shaped by the present in which that past was conceived? How have the Maya been transformed and incorporated into popular culture? What kinds of social and political factors influence which theories about the past are considered acceptable or dismissed?

November 17: Agenda

In this week's synchronous class meeting, we will:

1. Discuss the week's readings and videos (don't forget to also post to the Canvas discussion forum by 12 PM!).

2. Workshop one another's Shorthand media and outlines as a Breakout Group activity.

Order of Readings

1. David Webster, “The Mystique of the Ancient Maya”

2. Jesse Lerner, “A Fevered Dream of Maya: Robert Stacy-Judd,” Cabinet, 2001

3. Quetzil Castañeda, “Vernal Return and Cosmos: That Serpent on the Balustrade and the New Age Invasion”

4. “The Descent of Kukulkán” Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian

5. David Stuart, "Q & A about 2012" and WAMC's The Academic Minute

6. Leandro Katz, Paradox, (2001)

7. Pete Wells, "Why I’m Not Reviewing Noma Mexico"

8. Optional: "Rosalia Chay Chuc," Chef's Table BBQ, Netflix, 2019

Readings for Discussion

This week's materials overlap with some of our discussions from the fourth week of the quarter (October 20: Inventing "the Maya") in that they force us to ask how the complexities of people, culture, language, and history can be distilled into "essential" elements and, in turn, how those elements are appropriated in new media. While Week 4 focused on the people, culture, languages, and history being condensed, this week we turn to specific appropriations and their consequences.

The readings and videos for this week provide both an overview of the history of fascination with elements of ancient Maya culture (mainly from beyond the borders of Central America), as well as some of the specific realms in which that fascination has been expressed: modernist architecture, New Age religions, and haute cuisine. As you move through the materials, bear in mind some of the issues raised during our earlier conversations, particularly the ways in which ancient Maya language, art, and architecture have been severed from contemporary Maya culture, questions of "authenticity," and the economic impacts of commodifying cultures and their products.

1. David Webster, “The Mystique of the Ancient Maya”

This chapter, written by prominent Maya archaeologist David Webster (Professor Emeritus, Penn State University), explores what has been termed the "Maya mystique"—the idea that theancient Maya were a unique and uniquely accomplished ancient civilization. Webster traces the mystique to three interrelated factors: the history and practice of Maya archaeology in the field (much of which we discussed during our October 13: Big Digs session), the interpretations of that work published by influential figures in the field, and the assumption that because the Maya were both poorly understood and seemingly difficult to understand, they were a kind of "wild card" among ancient civilizations.

Webster's chapter reviews in detail the particular elements of the mystique and the kinds of interpretations it encouraged (some of which will be familiar to you from our earlier readings and discussions), as well as how they became an accepted "package" by the 1940s and 1950s. Webster also describes how continued research led scholars to question or debunk many elements of the mystique.

Access a PDF of David Webster's "The Mystique of the Ancient Maya" here.

As you read, keep the key question underlying this course as a whole in mind: how is knowledge about the past (whether accurate or not) produced, accepted, and replicated? More specifically, what led particular people to make particular claims about the ancient Maya? How did they ensure that their conclusions became long-lasting and widely accepted versions of the Maya past? How were those interpretations challenged and/or disproven (and by whom)? As Webster does, think about how various elements of archaeology (the people, the fieldwork practices, the publishing outlets, etc.) are entangled in those processes.

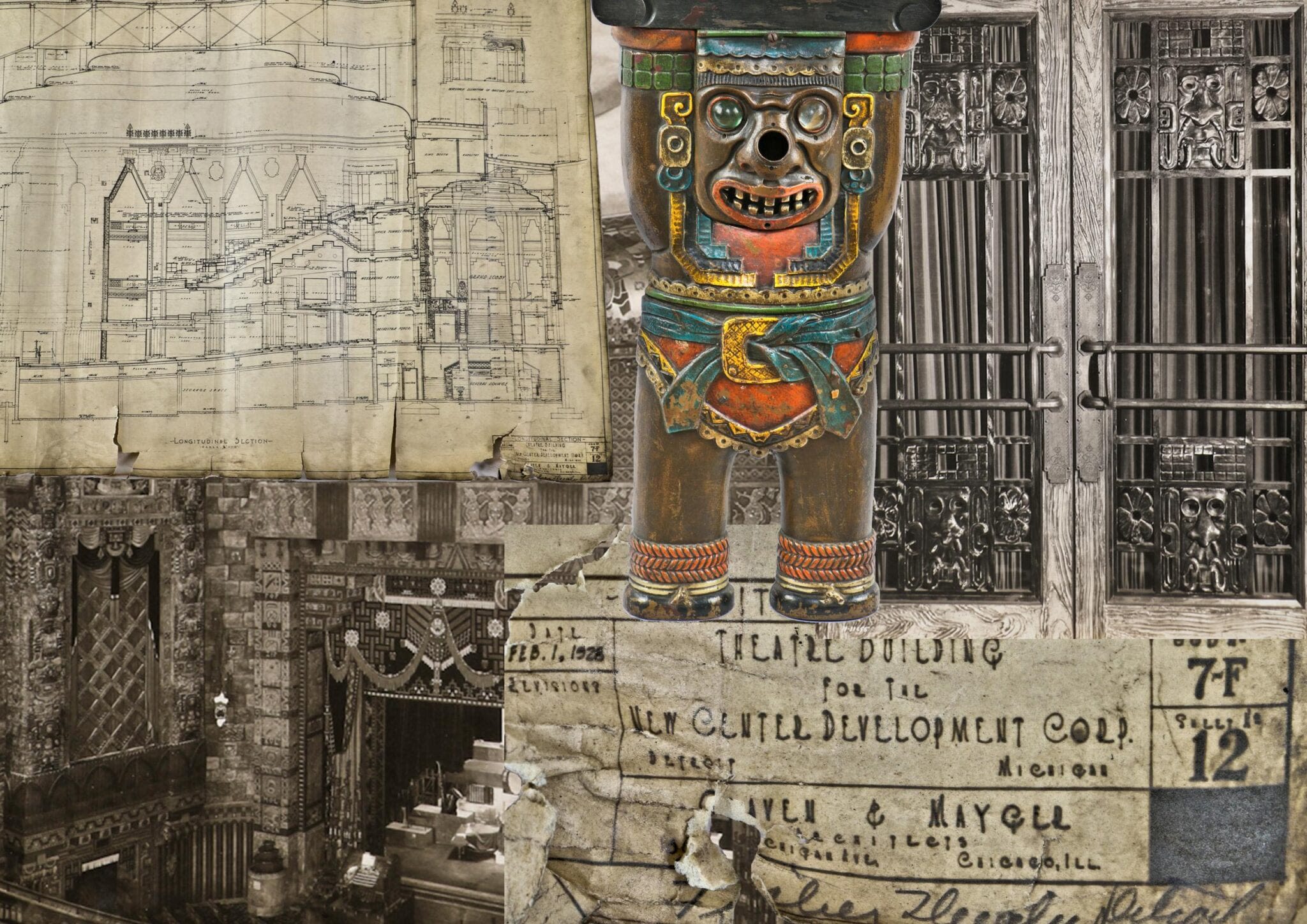

2. Jesse Lerner, “A Fevered Dream of Maya: Robert Stacy-Judd”

"Unlike other more formalist and modernist appropriations of the pre-Columbian past, such as those by Frank Lloyd Wright, Stacy-Judd’s buildings reveal a sensibility that is more theatrical than architectural. Stacy-Judd saw in the Maya the mawkish story of a lost Eden, enlivened by royalty and pomp, which he dramatized in colorful costumes, flamboyant architecture, romantic poetry, and speculative literature."

Robert Stacy-Judd was an early 20th-century British architect. In the 1920s, Stacy-Judd moved to Los Angeles, CA. Not long after, he discovered Frederick Catherwood's drawings of Maya ruins, which became a life-long inspiration (perhaps borderline obsession) for him.

Robert Stacy-Judd, architect, “Robert Stacy-Judd portraits,” UCSB ADC Omeka, accessed November 9, 2020, http://www.adc-exhibits.museum.ucsb.edu/items/show/446

Robert Stacy-Judd, architect, “Robert Stacy-Judd portraits,” UCSB ADC Omeka, accessed November 9, 2020, http://www.adc-exhibits.museum.ucsb.edu/items/show/446

Stacy-Judd's most famous building (and best example of his "Mayan Revival" style, was the Aztec Hotel in Monrovia, CA, constructed in 1924.

Two women outside the Aztec Hotel, located at 311 West Foothill Boulevard in Monrovia, CA, Security Pacific National Bank Collection/Los Angeles Public Library.

Two women outside the Aztec Hotel, located at 311 West Foothill Boulevard in Monrovia, CA, Security Pacific National Bank Collection/Los Angeles Public Library.

Jesse Lerner's article from Cabinet magazine puts Stacy-Judd's fascination with the Maya in its historical context, caught between earlier U.S. imperialist tendencies toward Latin America and later efforts at friendship and unity, caught up in American ideas about indigenous authenticity, and dovetailing with the popularity of secret societies and fraternal organizations for middle-class men.

Access Jesse Lerner's “A Fevered Dream of Maya: Robert Stacy-Judd” here.

Although Stacy-Judd's fascination with the Maya past echoes similar tropes we've seen in earlier readings (e.g., the tourists at Xunantunich), his motivations are the peculiar product of his time. As you read, think about that connection between the present moment and the draw of the past for Stacy-Judd—have you seen it echoed by archaeologists, historians, art historians, or other academics who study the ancient Maya?

4. Quetzil Castañeda, “Vernal Return and Cosmos: That Serpent on the Balustrade and the New Age Invasion”

This chapter comes from anthropologist Quetzil Castañeda's book, In the Museum of Maya Culture: Touring Chichén Itzá. Castañeda's book is now almost a quarter of a century old (published in 1996), but it is still considered a landmark study of archaeology and tourism. Based on ethnographic work in Pisté, a Maya town adjacent to the ruins of Chichén Itzá, and at the archaeological site itself, Castañeda's ambitious project traces out the ways that the invention of the Maya as a culture involves the intersecting interests of Maya peoples, anthropological practices, tourism and business, regional politics and nation-building, New Age spirituality, and international relations between Mexico and the United States.

In "Vernal Return and the Cosmos," Castañeda describes the celebration of the spring equinox at Chichén Itzá, where a crowd of tens of thousands of tourists, primarily from Mexico and the United States, gathers to watch as the setting sun creates the image of a serpent of light, seemingly cascading down the balustrade of the pyramid known as El Castillo. Castañeda's description of the event in the chapter is based on his experience in 1988 and 1989, but it remains a major draw and carefully orchestrated event for international tourists to this day (though many changes have taken place in programming and participation since the late 1980s).

Castañeda details how the various "cultural performances," including songs, dances, and theater, serve to create a regional Yucatecan identity, while at the same time reinforcing the exclusion of the Maya from that identity. He also describes a scene of almost-violent conflict among some of the various groups of religious pilgrims who celebrate the spring equinox: neo-Aztecs (Aztecas) or the White Brotherhood of Quetzalcoatl, Anglo-American "Maya" devoteés, Mexican gnostics, and seasonal U.S.-based spiritualists known as the Rainbow Family and between those groups and state officials.

Access a PDF of Quetzil Castañeda's “Vernal Return and Cosmos: That Serpent on the Balustrade and the New Age Invasion” here.

As you read, consider whether or to what extent the kinds of cultural appropriation Castañeda exposes at Chichén Itza compare tothose of Robert Stacy-Judd. Is there a difference between "Mayan Revivial" architecture and New Age "Maya" theology? What impacts do various forms of borrowing, rewriting, and (re)inventing the past have on the present?

4. Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian: "The Descent of Kukulkán"

The brief video below shows a time-lapse of the appearance of Kukulkán along the balustrade of the Castillo pyramid at Chichén Itzá at the equinoxes.

Having read Castañeda's withering critique of all aspects of this event, think about its presentation in the video. What is communicated by the music, the erasure of the crowds, even the fact that the video is produced by the Smithsonian Insitution and the National Museum of the American Indian?

5. David Stuart, "Q & A about 2012" and podcast from The Academic Minute

As many of you recalled during Week 4's Breakout Group activity, 2012 was a key moment for the collision between the ancient Maya and modern popular culture. In this blog post (from 2009), epigrapher David Stuart provides a brief overview of the facts around the supposed "end" of the Maya calendar. In a later podcast (from 2012) he also discusses recently recovered texts from the site of La Corona, in Guatemala, which also references the 13.0.0.0.0 bak'tun ending of 2012 (and was unearthed only a few months before the infamous December 21 date).

While reading the blog post and listening to the podcast, think about how the 2012 phenomenon intersects with both the "Maya mystique" described in David Webster's chapter and the various forms of New Age spiritualism highlighted by Castañeda.

6. Leandro Katz, Paradox (2001)

Leandro Katz is an Argentinian writer, artist, and filmmaker. Much of his visual work combines anthropological or historical research with photography and moving images. Among Katz's many influences, the pre-Columbian and contemporary Maya stand out, including in works like "The Catherwood Project," in which (before Jay Frogel) Katz followed in the footsteps of Stephens and Catherwood's expedition. Between 1985-1995, Katz visited sites illustrated by Catherwood and took a series of photos of Catherwood's drawings at the locations where they were originally made:

Leandro Katz: "Uxmal, Casa de las Palomas (1993)." Gelatine silver print, 16x20 inches.

Leandro Katz: "Uxmal, Casa de las Palomas (1993)." Gelatine silver print, 16x20 inches.

Paradox is a short, experimental documentary film that studies the cultivaiton and processing of bananas at a plantation near the ancient Maya city of Quiriguá, Guatemala (described and documented by Stephens and Catherwood as well). Be warned: it is brutally deadpan, the sustained shots of stone monuments from the archaeological site or local residents looking directly into the camera mimic the repetitive, never-ending labor that he documents on the plantation. There are no dialogues, no voice-overs, and no interviews.

The stark contrast between the mind-numbing exploitation of the present and the sculptural glory of the past explicitly calls attention to the human and environmental costs of colonialism. It also more subtly recalls the earlier practices of claim-staking, looting, and export at Quiriguá by Stephens, who had hoped to purchase the site and ship the entire city to New York (in the end, he shipped only a few monuments, which were destroyed in the same fire that cost Catherwood most of his images).

As Jesser Lerner (author of the Cabinet magazine article on Robert Stacy-Judd, above) writes:

"Where Catherwood's images showed indolent, faceless natives, lounging languidly, oblivious to the faded glory and potential riches that surround them, Katz depicts frenetically busy wage slaves, the bottom runs of a transnational global economy that extracts riches from the "undeveloped" south and packages them for export."

The scenes of the ancient carved monument from Quiriguá (known as Stela P) are long, but the pace is intentional. Pay attention to the contrasts Katz sets up, particularly at the end of the film: stasis and progress, riches and resources, captives and capitalism.

Watch Leandro Katz's Paradox here.

7. Pete Wells, "Why I’m Not Reviewing Noma Mexico"

Following on the themes of imperialism and extraction highlighted in Katz's film, this short article from New York Times food critic Pete Wells offers a glimpse of another, less obvious, arena in which natural and cultural resources (from agricultural products to indigenous culinary knowledge) are pulled from their local context in order to be sold (at outrageous prices) on the global market.

Tickets to eat at Danish chef René Redzepi’s seven-week pop-up restaurant in Tulum, Noma Mexico, sold out in two hours, despite the fact that a meal for a table of four (with tax, etc.) costs $3,000 and had to be paid at the time of booking (almost twice what Noma charged for its previous pop-ups in Sydney or Tokyo). The average meal in Mexico costs $4, where the average wage is $15 and the poverty rate is 46%.

Access Pete Wells's "Why I’m Not Reviewing Noma Mexico" here.

As Wells notes in his non-review, it is difficult to grapple with "the idea of a meal devoted to local traditions and ingredients that is being prepared and consumed mostly by people from somewhere else." The LA Times food critic, Jonathan Gold (who, unlike Wells, did travel to Noma Mexico and, like everyone else, raved bout the meal), wrote:

"The hard questions of context and appropriation remain. Noma Mexico does indeed serve $600 dinners in a fairly poor part of the world, and the intricate supply lines it established with local farmers are likely to evaporate not long after the crew packs up to return to Denmark. The restaurant is making a statement that belongs to Mexicans to make. Arguments about localism and sustainability may seem trite when most of the customers travel thousands of miles to eat a meal...But in a way, it may be like criticizing Francis Ford Coppola for filming in the Philippines or V.S. Naipaul for setting a novel in Africa: Redzepi is creating something that otherwise would not exist. Beauty and conflict are often intertwined.

As you read Wells's article, ask yourself whether there are hierarchies of appropriation and exclusion—is Robert Stacy-Judd's "Mayan Revival" architecture somehow better or worse than René Redzepi's raw cacao fruit, served to people who pay thousands of dollars for the experience? Is the meal at Noma Mexico, served in the shadow of Tulum's archaeological ruins and resort-hotels, somehow better or worse than the banana plantations near Quiriguá? What about the Western New Age spiritualists, whose goal Castañeda describes as "to learn the spirituality and knowledge of 'the Maya' in order to become Maya themselves" (p. 186) - where do they sit in such hierarchies (if they exist)?

8. Optional: Netflix's Chef's Table, "Rosalia Chay Chuc"

This episode of Netflix's documentary series Chef's Table centers on Rosalia Chay Chuc, a Yucatec Maya chef from the town of Yaxunah. Two well-known Mexican chefs, Ricardo Muñoz and Roberto Solís, "discovered" Rosalia's cochinita pibil (pork slow-cooked in an earth oven, or pib) while on a trip in Yucatan to find new foods and ingredients for their own restaurants in Mexico City.

Watch Netflix's Chef's Table, "Rosalia Chay Chuc," here (requires Netflix subscription).

The episode highlights Rosalia's daily life in Yaxunah, as well as her many artistic talents (primarily cooking, but also sewing) and the ways that knowledge is passed among generations of women. Toward the end of the episode, it also connects back to René Redzepi's Noma Mexico, where Rosalia and other women from Yaxunah were hired to make tortillas during the restaurant's run in Tulum.

Since being featured on the Netflix show, Rosalia has begun offering culinary classes and tours of the region (including archaeological ruins) around Yaxnah. If you're interested, take a look at the descriptions on her website here.

The Netflix documentary offers a stark contrast to Leandro Katz's film: not just in the optimism and celebration of Chef's Table versus the pessimism and despair in Paradox, but also in the glossy, staged shots versus the long, rough-cut exposures and underlying message that worldwide interest local products (in the Netflix case, Rosalia's cooking) is unquestionably a good thing.

Consider the Chef's Table episode in light of the forms of cultural appropriation we're thinking about this week, but also with respect to some of the questions that have come up in previous weeks about "authenticity," ethno-tourism, and the commodification of culture. Is the Netflix documentary different (if so, better or worse?) than Les Mitchel's Maya are People or the Lambs' Quest for the Lost City?

Breakout Group Activity: Shorthand Media/Outline Peer Workshopping

For this week's Breakout Group activity, you will view and comment on the outline of your partner's Shorthand page.

In providing feedback on your partner's page, consider the following:

1. Has your partner uploaded the minimum required images? (There should be at least 1 map, 6 images, 1 video, and 1 animation). If they have not, why not? (If it doesn't make sense to include, for example, a video or a map, what have they replaced that element with?).

2. Does the page provide a general outline (the text does not need to be finalized) indicating the topics that will be addressed in the final version? Does the outline make sense to you? Is a particular topic missing or difficult to understand?

3. Keep in mind that your Shorthand pages should explore the kinds of theories and themes discussed in this class, but in a particular context beyond the scope of the syllabus. Knowing what you know about Maya archaeology, what issues might your partner want to address with their page? How do you see it fitting into the overarching aims of the course? What does it contribute that is new (i.e., beyond the scope of the syllabus)?

4. Although you only have the outline thus far, does the Shorthand page seem well positioned to speak to varied audiences? It should be interesting and intelligible to both other students in this course and other members of the university community who do not have the same specialized knowledge you've gained over the course of the quarter.