November 3:

Reading Maya Writing

How and when was Maya writing deciphered? Did it happen suddenly or slowly? How did that process compare to the decipherment of other writing systems? How did decipherment change the interpretation of Maya history and material culture? What kinds of work come after decipherment?

November 3: Agenda

In this week's synchronous class meeting, we will:

1. Begin with a conversation/Q&A session with our invited speakers, Professor Theo van den Hout of the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago and Professor Marc Zender of Tulane University (don't forget to post questions for Professors van den Hout and Zender to the dedicated Canvas questions forum by 12 PM!)

2. Discuss the week's readings and videos (don't forget to also post to the Canvas discussion forum by 12 PM!)

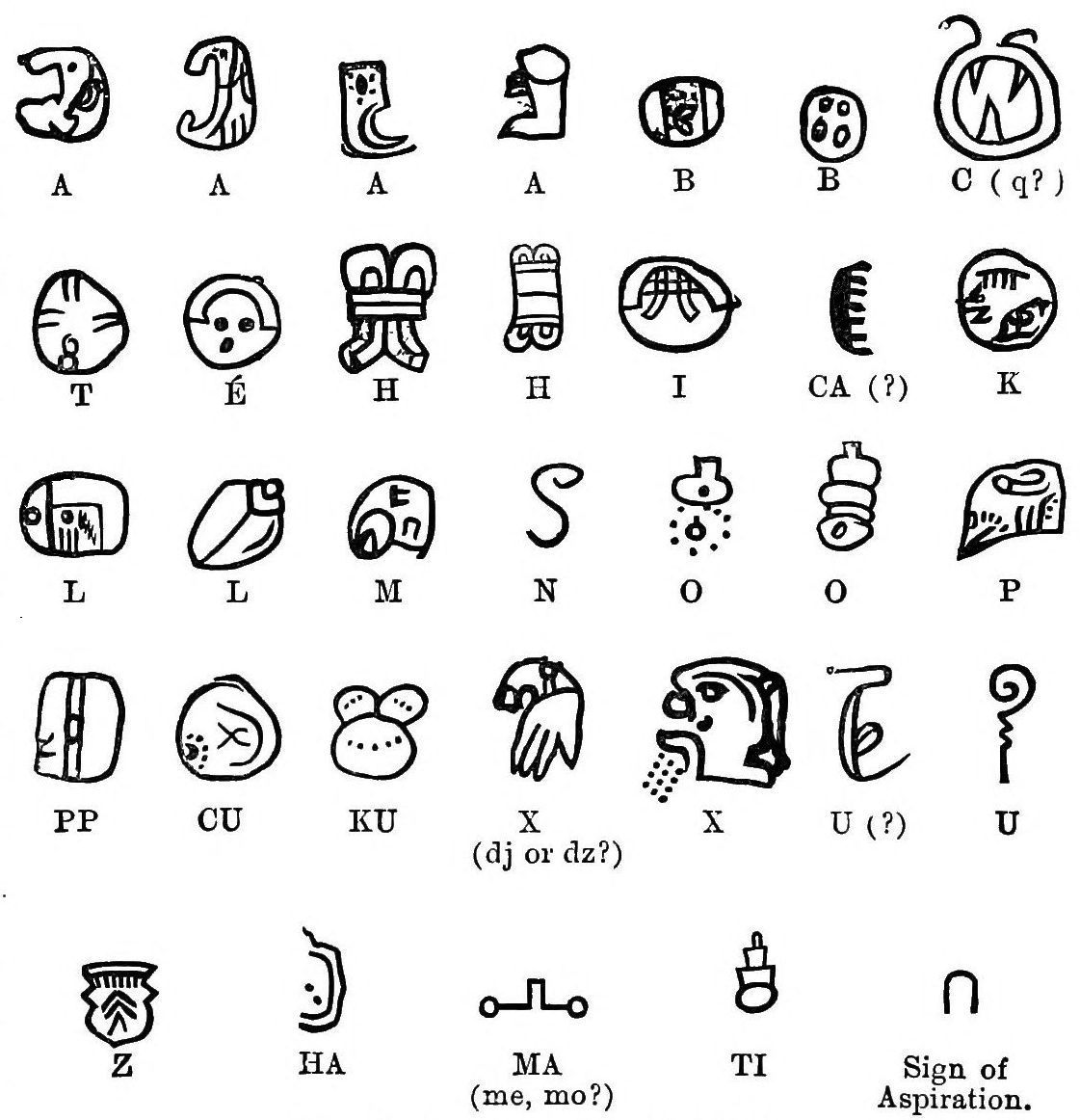

3. Complete a Breakout Group "Digging the Glyphs" activity, which will give you a chance to decipher Classic Mayan syllabograms firsthand.

Readings for Discussion

The decipherment of Maya hieroglyphic writing has been a common undercurrent in several of our previous discussions: the need to revise late 19th and early 20th centuries once Classic Maya history could be read, the key breakthrough made by Tatiana Proskouriakoff in recognizing personal life events in the monuments of Piedras Negras, and the role hieroglyphic writing plays in contemporary language revitalization efforts, like the stela at Iximche'. This week, we will focus on the history, process, and future of Maya decipherment, alone and by comparison to another ancient script: Anatolian hieroglyphs. As you review this week's varied materials, bear in mind the key questions outlined above. In particular, note how serendipitous moments, sustained engagment and debate, and ongoing challenges are involved in reading Maya writing.

1. Nightfire Films, Breaking the Maya Code

Breaking the Maya Code is largely based on a book of the same name by Michael D. Coe. In that book, Coe describes the decipherment of Maya hieroglyphic writing as "one of the most exciting intellectual adventures of our age"—an achievement that Coe puts on equal footing with the exploration of space and the discovery of the genetic code.

In his preface to the book, Coe wrote:

"[I]t will soon become apparent to the reader, as it has to me, that the course of this decipherment has involved not just theoretical and scholarly issues, but flesh-and-blood individuals with strongly marked characters...let me say here that there are really no 'bad guys' in these pages, just well-meaning and determined scholars who have sometimes been impelled by false assumptions to take wrong turns, and had their posthumous reputations suffer as a consequence."

As you watch Breaking the Maya Code, think about the way the process of decipherment is portrayed. Is it a celebration of collaborative achievements or of singular individuals' remarkable insights?

Watch Breaking the Maya Code via kanopy below (requires UChicago login)

In addition to tracing the history of Maya hieroglyphic decipherment, Breaking the Maya Code will introduce you to some of the fundamentals of Classic Mayan script. That knowledge and vocabulary will make it easier to follow and to understand the importance of the remaining readings for this week.

2. Marc Zender, “Theory and Method in Maya Decipherment"

NOTE: Pages 1-14 (up to "Distributional Criteria) are required reading, pages 14-37 are optional

Where Breaking the Maya Code (whether book or film) explicitly sets out to position the decipherment of Maya hieroglyphs as an exceptional achievement, Zender's comparative review of the methods and theory of decipherment show that such breakthroughs are only possible when a rigorous, empirical method—one that has been tested against ancient scripts around the world for centuries—is meticulously applied to accumulated evidence.

Zender details how all decipherments follow similar patterns and rely on similar kinds of evidence and explains the "five fundamental pillars on which all successful decipherments have rested" (first outlined by Coe). He also outlines how decipherments progress and some of the checks that can be used to confirm, reject, or refine a particular reading (including new archaeological finds bearing texts or inscriptions).

Access a PDF of Marc Zender's “Theory and Method in Maya Decipherment" here.

In this article, Zender also directly engages with a particular critic of the decipherment of Maya hieroglyphic writing, Matthew Watson. In brief, Watson's articles and subsequent book argue that Maya hieroglyphic writing has not actually been deciphered—it only appears as a fully functional writing system because of the ways in which a small collective of epigraphers have manipulated the techniques of decipherment and "staged discovery" for amateurs to make their arguments seem incontestable. I've included one of Watson's articles as an optional reading for this week, but be aware (and critical) of the fact that Watson himself does not know how to read Maya hieroglyphic texts and his claims are based on his attendance at a single conference in 2008. In addition, his arguments rest on the erroneous assumption that decipherment happens at such public events, rater than is disseminated at them.

Optional: Access a PDF of Matthew Watson's “Staged Discovery and the Politics of Maya Hieroglyphic Things” here.

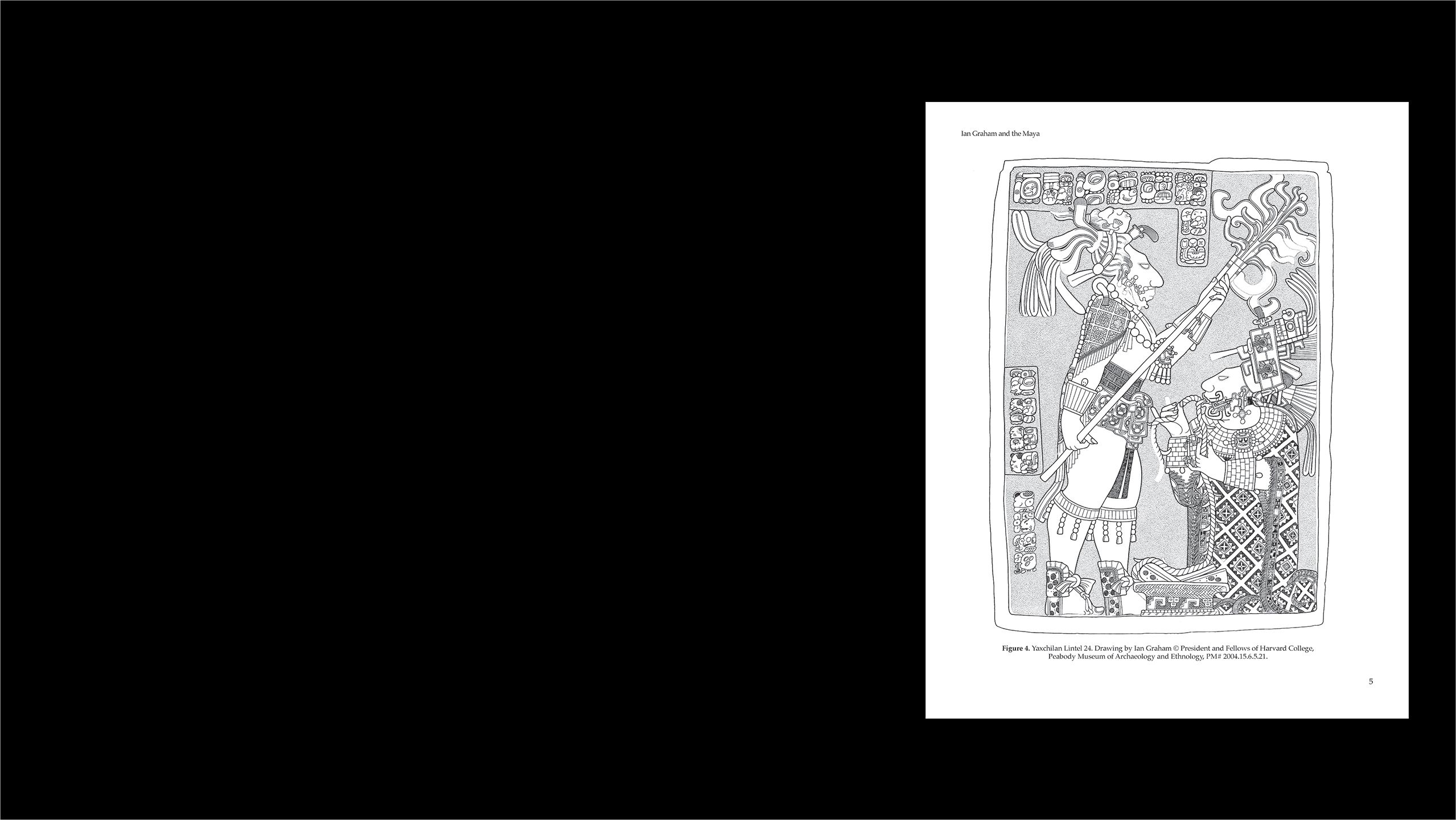

3. Ian Graham, “The Corpus Program”

This selection is taken from Ian Graham's autobiography, The Road to Ruins (2010). Over an impressive 502 pages, The Road to Ruins chronicles Graham's long and extraordinary life, including his invaluable contributions to the development of Maya archaeology (Graham died in 2017 at the age of 93).

Ian Graham was perhaps the last of the particular type of academically untrained, self-funded, and incredibly influential explorer that has emerged multiple times in our readings since John Lloyd Stephens's Incidents of Travel. Born to aristocratic parents in Suffolk, England, Graham was sent to boarding school as a child and educated at Cambridge University and Trinity College, Dublin. Graham never had any formal training in archaeology, but after World War II he bagan working as a technician in the art conservation lab at the National Gallery in London, where he specialized in photography.

In 1958, Graham took a long detour through Mexico on a road trip from New York to California, where he heard about the existence of the Maya and the ruins of Yaxchilan (in Chiapas) for the first time. Graham thought Maya would make for an excellent photography book and began traveling through Chiapas, Yucatan, Belize, Honduras, and northern Guatemala. As his contacts in Maya archaeology grew, Graham's efforts were sponsored in part by Tulane University's Middle American Research Institute, which published Graham's Archaeological Explorations in El Peten, Guatemala in 1967. Graham's book included finds from numerous sites that few Maya archaeologists even knew existed at the time, including Aguateca, Dos Pilas, Machaquila, Kinal, Nakbe, and El Mirador (which you'll remember from the VICE News video for the week on "Big Digs"). Graham was the first person to survey El Mirador and realize the massive scale of the site, which he published in a brief newspaper account in 1962.

This chapter picks up after the publication of Archaeological Explorations in El Peten, Guatemala. Some familiar names will resurface in Graham's description of the origins of the Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions (CMHI), including Bill Coe, the director of the University of Pennsylvania's Tikal Project, and the lingering legacies of the CIW at Harvard University.

Access a PDF of Ian Graham's chapter on "The Corpus Program" here.

Pay attention to the motivations behind the funding Graham was eventually able to secure for the CMHI in light of the five fundamental pillars outlined in Zender's article—producing a corpus of available and reliable source material is an essential step in the process of decipherment. Note also the choices that needed to be made in the creation of that corpus (what would be recorded, to what standards, how information would be presented, etc.), what those decisions were based on, and how they impacted the publication process of the CMHI. Although Graham modestly described himself in The Road to Ruins as "a bushwhacker outfitted with a camera, compass, pencil, some grains of common sense, and an instinct for self-preservation" (p. 292), in the words of epigrapher David Stuart:

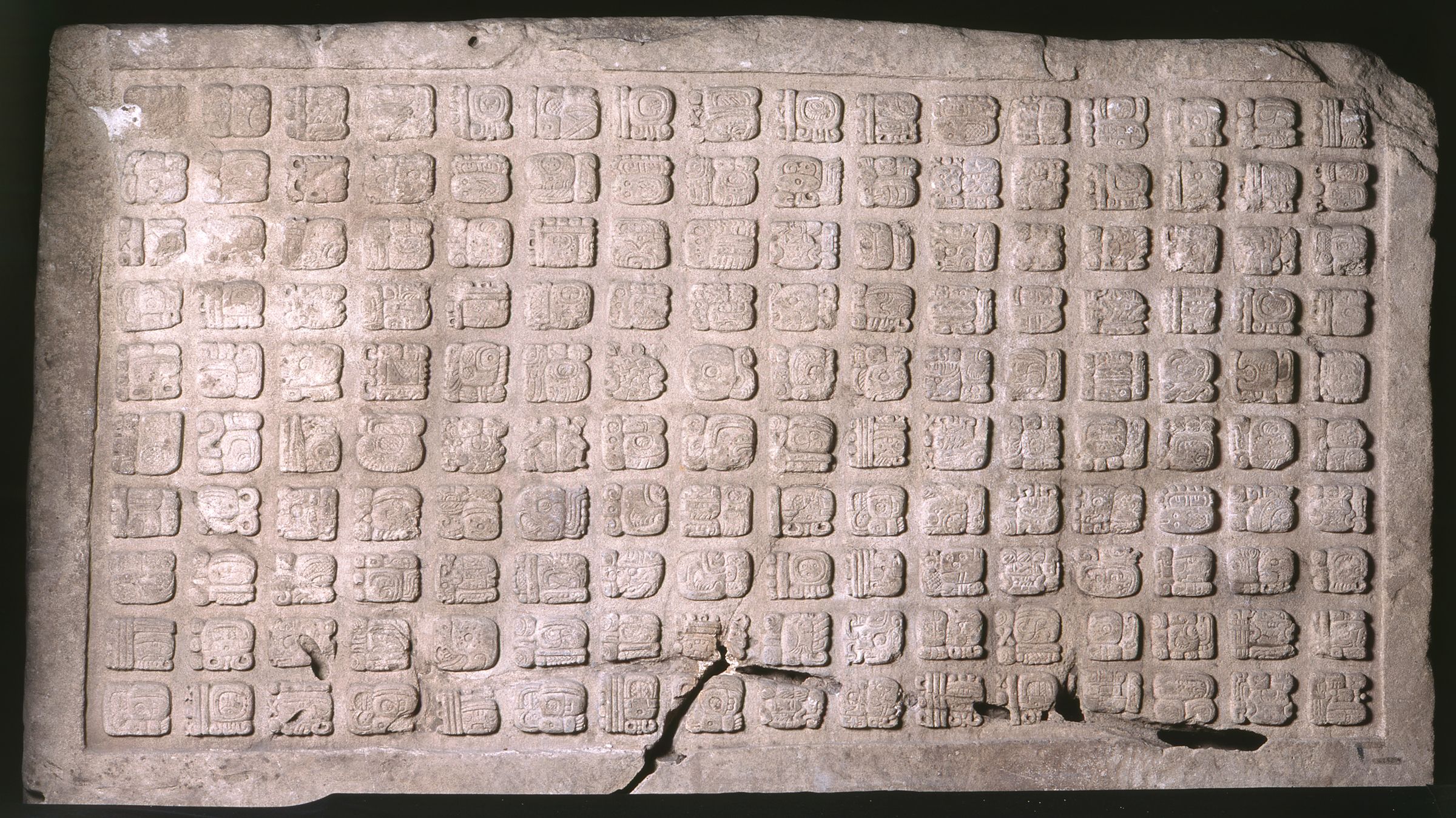

"Ian's drawings stand on their own merits as stunning artworks. Their intricate line-work and careful stippling set a new standard for accuracy and objectivity, built on that first developed by William Coe of the Tikal project. In those days and until very recently the drawings were producing using ink on mylar, tracing over a preliminary acetate version that was, in turn, traced from a photograph. A pencil field drawing, ideally made in the presence of the original sculpture, provided a check for all the relevant details of sculpture. In this way Ian created the ideal standard for the recording of Maya monuments...The photocopies of field drawings and other output from the CMHI provided the single most important catalyst to the rapid decipherment of Maya hieroglyphs, a wave that crested during the 1980s. Hundreds of new texts were now available to the small community of epigraphers of that time, and no longer were source materials largely restricted to a handful of well-known sites. By generously sharing his visual archive, Ian provided epigraphers with much-needed raw materials to compare texts, analyze alternative spellings, and track dynastic histories. Without these basic raw materials to work from, little real progress would have been possible in deciphering the Maya script and analyzing the Classic Mayan language that underlies it."

Optional: The website for the CMHI is currently being updated, but you can still view some of Graham's photos and drawings here.

4. Simon Martin and Nikolai Grube, Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens

Simon Martin and Nikolai Grube's book provides in-depth dynastic histories for eleven ancient Maya cities based on textual sources and archaeological data. Choose any chapter and browse through it to gain a sense of the temporal specificity, dynastic histories, and geopolitical shifts that came to light with the decipherment of Maya hieroglyphic writing.

NOTE: You will need to click the LOG IN button at the upper right corner and sign in with your UChicago CNetID to use the viewer below. If you prefer, you can also find the volume through the library webpage.

5. Stephen Houston and Simon Martin, “Through seeing stones: Maya epigraphy as a mature discipline”

"Is every Maya house mound, far-flung village, economic activity, or modest person illuminated by the glyphs? No. Is our understanding of the overall society and its framing concepts deepened? Undeniably."

This article builds on both the history of decipherment presented in Breaking the Maya Code, the comparative theories and methods detailed by Marc Zender, and the challenges of standardized collaboration raised by Graham's Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions. Here, Stephen Houston and Simon Martin (two epigraphers who—as they note—have over 60 years of combined experience studying Maya hieroglyphic writing) review some the steps toward and key moments of decipherment that will by now be quite familiar to you, but they also outline some of the challenges that have arisen now that texts and inscriptions can be read.

Access a PDF of Stephen Houston and Simon Martin's “Through seeing stones: Maya epigraphy as a mature discipline” here.

As you read, pay particular attention to the limits of ancient voices (both whose are heard and what they can tell us), the ethical issues involved in unearthing new texts and in reading those that have been illicitly excavated, and the changing nature of the field of Maya epigraphy. Bear those questions in mind as you turn to the comparative case study we will examine this week: Anatolian hieroglyphs.

6. Maurice Pope, “Luvian Hieroglyphic”

This chapter comes from a comparative volume titled The Story of Decipherment: From Egyptian Hieroglyphs to Maya Script. You'll notice many of the same themes discussed in Marc Zender's article in Pope's chapter, particularly the ways in which the "five fundamental pillars" affect not only the very possibility of decipherment, but also the speed at which the process takes place. Pope's chapter also highlights how the decipherment of one script (Cypriot, in this case) can influence the theories and methods by which subsequent scripts may be approached (which can sometimes result in errors).

Access a PDF of Maurice Pope's chapter on "Luvian Hieroglyphic" here.

As you read, think about the way the process of decipherment is presented in Pope's account—what he calls "the least dramatic of all"—in comparison to the way the process was presented in Coe's account (retold in Breaking the Maya Code).

7. William Mullen, "Deciphering a Link to Past"

This Chicago Tribune article from 1997 features the Chicago Hittite Dictionary Project (or CHD) of the University of Chicago's Oriental Institute. The article provides some background to the CHD project, which was started in 1976 by Hans Guterbock and Harry Hoffner, Hittite scholars at the Oriental Institute at the time. (Our guest this week, Professor Theo van den Hout is currently the executive editor of the CHD and the author of a key text for studying the Hittite language: The Elements of Hittite.)

Access William Mullen's "Deciphering a Link to Past" here.

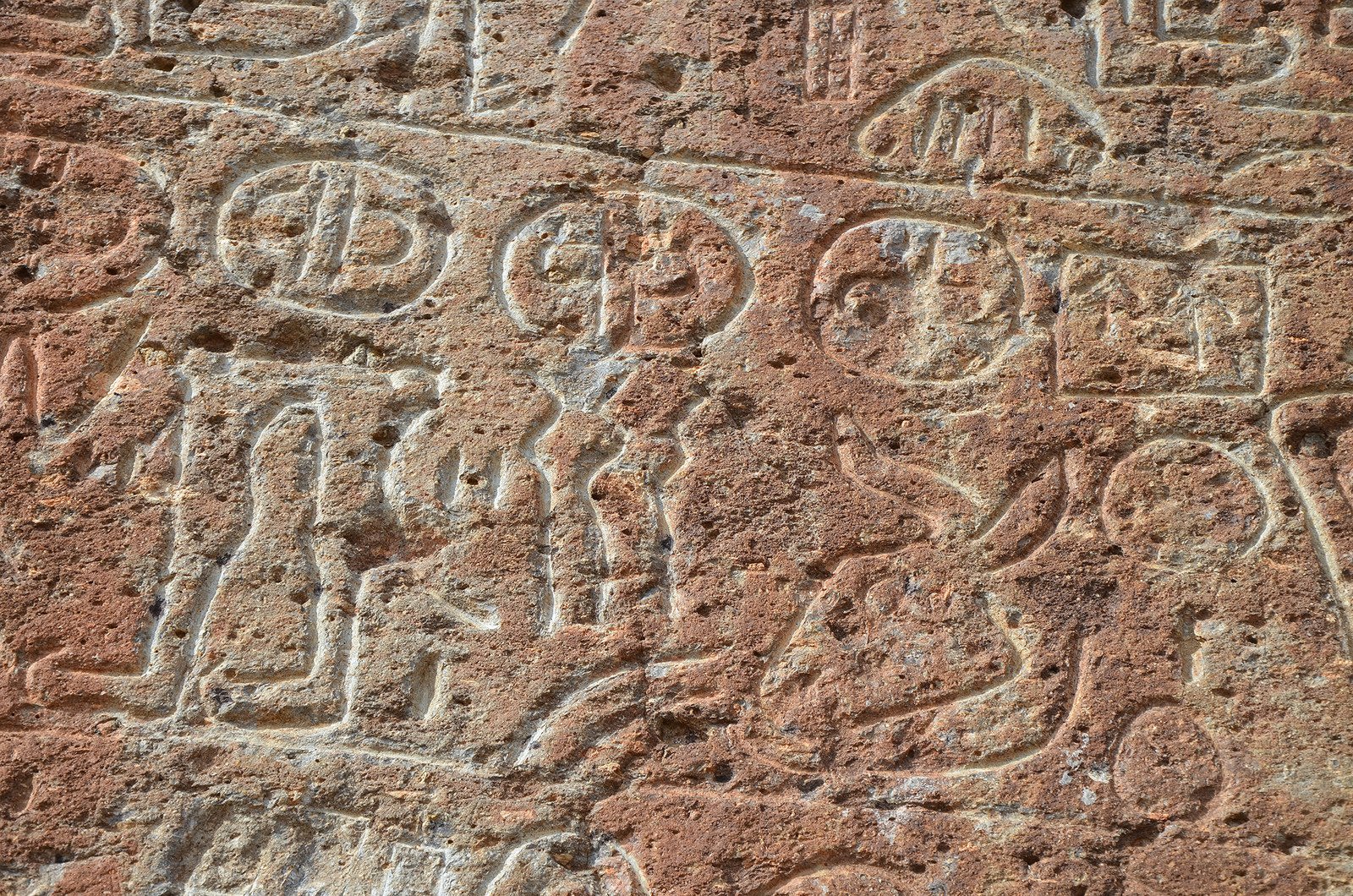

Although the article is short, it highlights some of the unusual decisions required by collaborative efforts in "necrolexicography," as well as the painstaking nature of the process. Note where in the alphabet the CHD project began (and why), as well as the letters that were completed in 1997. As noted by Houston and Martin above, ongoing archaeological work and new finds both add new insight to and complicate such efforts. In fact, Professor van den Hout, along with his colleagues Petra Goedegebuure and James Osborne of the Oriental Institute, published a new Luwian inscription just this year (discovered during Osborne's archaeological survey in Turkey in 2019). If you are interested, you can read access the publication of that new inscription here.

Think comparatively about the necrolexicographic efforts being made in the fields of Maya and Anatolian hieroglyphs. What challenges do they share and what issues are unique to the particular languages, the contexts in which they were written, or even the specific ethical concerns that may be wrapped up in their study?

8. The Oriental Institute, "Chicago Hittite Dictionary Project"

This short pamphlet from the Oriental Institute provides a more recent update on the CHD project (from 2010). It goes into more detail than the Chicago Tribune article about the motivations behind the dictionary, the ways in which it is intended to be used, and the nature of the information it contains (see, in particular, the example entry on p. 3). It also provides information about the ongoing digital life of the CHD.

Access a PDF of the Oriental Institute's "Chicago Hittite Dictionary Project" pamphlet here.

Think specifically about the CHD Project and the CMHI - how are these two endeavors related? In what ways are they quite different from one another? In reviewing the motivations behind, the progress made, and the challenges faces by the two programs, what lessons do they have to offer one another (or still-undeciphered writing systems like the Indus script or Easter Islands rongorongo)?

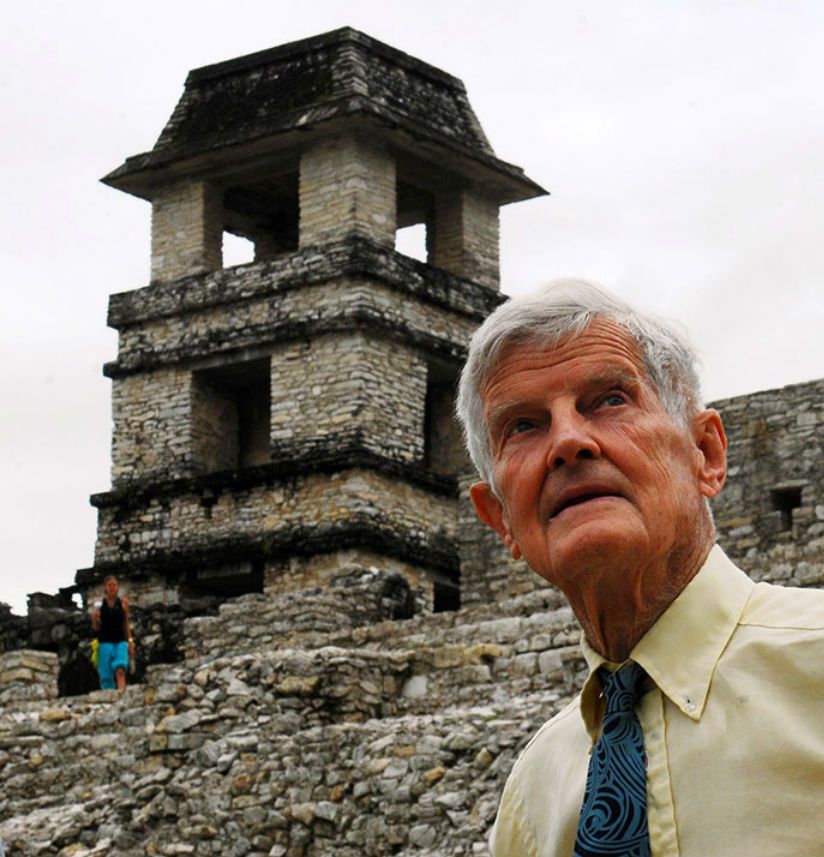

Marc Zender, Tulane University

Professor Marc Zender is an anthropologist and archaeologist, linguist, and epigrapher. His research and teaching are centered on anthropological and historical linguistics, comparative writing systems, and contemporary and historically-attested Mesoamerican languages (especially their origins, development, and eventual abandonment during the Colonial era). Professor Zender has conducted archaeological and epigraphic fieldwork throughout Mexico and Central America and has made major contributions to reconstructions of Mesoamerican indigenous languages, our knowledge of ancient writing systems from the region, and, of course, the ongoing decipherment and interpretation of Maya hieroglyphic writing.

Professor Zender has personal experiences with and connections to many of the various topics we are addressing this week. He is at the forefront of Maya decipherment and prior being a professor at Tulane University Professor Zender, he was a research associate at the Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions at Harvard. He has also taught survey courses on ancient writing systems from around the world, including an online course for public audiences called "Writing and Civilization: From Ancient Worlds to Modernity" (with The Great Courses). As you know from his article assigned for this week, he has considered the theories and methods behind the process of decipherment of Maya hieroglyphs in comparison to the decipherment of other ancient writing systems.

Optional: This short video will give you a sense of the questions that motivate Professor Zender in his archaeological and epigraphic research, as well as how the geopolitical landscape revealed by the decipherment of Maya hieroglyphs has sparked new interest in archaeological sites beyond major city centers (such as Cahal Pech, Belize).

Theo van den Hout, University of Chicago

Professor Theo van den Hout is the Arthur and Joann Rasmussen Professor of Western Civilization and of Hittite and Anatolian Languages at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. Professor van den Hout is a distinguished philologist and, as mentioned above, chief editor of the CHD Project and the author of a key resource for learning the Hittite language, Elements of Hittite. Professor van den Hout's recent research has explored ancient record management, literacy and writing, and visual culture in Hittite society.

Professor van den Hout provides an Anatolianist's perspective to the questions we are exploring this week. He has tackled many of the challenges that Mayanists currently face (or that may await them), including how to approach an exhaustive bilingual dictionary, how to craft a lucid and succinct textbook for beginning learners of an ancient writing system, and how to incorporate newly discovered texts into both those efforts and the bigger picture of geopolitics in Anatolia during the Bronze and Iron Ages.

Optional: In this recent video podcast, Professor van den Hout highlights the historical information that he is able to glean from ancinet textual records by examining the complex political relationships between the Hittites and the Egyptians in the 14th century BC.

Breakout Group Activity: Digging the Glyphs

In this simple exercise, you will work with a partner to decipher a series of Maya hieroglyphs.

Access a PDF of the "Digging the Glyphs" activity here.

When you have finished, upload your answers to the Breakout Group assignment in the November 3 Canvas module (one upload per Breakout Group is fine—you may edit and re-upload the PDF, print and take upload a photo of the worksheet, or simply type your answers as text).