October 27: (Re)Making Maya Art

Of the many material remains of the ancient Maya past, which do scholars label “artifacts” and which do they label “art”? How do those labels affect the way material culture is studied, manipulated, conserved, or displayed? What visualization techniques (e.g., artistic reconstructions, 3D scanning, etc.) have facilitated the study of ancient Maya material culture? Traditionally, who is/has been responsible for those products? Should drawings, reconstructions, and scans be considered raw data or expert interpretations?

October 27: Agenda

*Please note that your Shorthand proposals are due this week (the assignment deadline is 11:59 PM on October 26*

In this week's synchronous class meeting, we will:

1. Begin with a conversation/Q&A session with our invited speaker, Professor Heather Hurst of Skidmore College (don't forget to post questions for Professor Hurst to the dedicated Canvas questions forum by 12 PM!)

2. Discuss the week's readings and videos (don't forget to also post to the Canvas discussion forum by 12 PM!)

Readings for Discussion

This week's materials cover a wide range of questions around the topic of ancient Maya art. We will begin with the most fundamental: what is "art"? Has the concept always existed? Did it exist those people in the past who made objects that are now considered to be art in the present? Sometimes looking beyond the Maya world (both geographically and temporally), we will also ask how specialists (including our invited guest this week, Professor Heather Hurst) have developed a variety of methods to understand processes and techniques of artistic production. Finally, we will consider not only how those methods and their results shape scholarly understandings of ancient art, artists, and viewers, but also examine the study of Maya art in relation to Maya archaeology, including some deeply rooted gender dynamics.

1. Carolyn Dean, "The Trouble with (the Term) Art"

In this article, Carolyn Dean, an art historian specializing in the pre-Columbian and colonial Andes, calls attention to some of the problems underlying Western recognition of non-Western (long termed "primitive" art). As Dean (p. 25) notes, "the assumption that art is a universal that can and perhaps should be found in every society in every historical period pervades the discipline," yet what "art" is has proven difficult to define and has changed across time and space, even in Europe, where the concept originated. What does it mean to identify "art" in places or societies where it did not exist as a concept? Is it even possible to recognize "art" in a way that does not simply reflect and reify its Western form as the ideal?

Access a PDF of Carolyn Dean's "The Trouble with (the Term) Art" here.

As you read, consider what the term "art" does to/for an ancient object or image. What are the implications of naming something as "art"? In particular, note the examples Dean provides of the ways in which 1) we need not explicitly name something as "art" in order to (re)create it as an art object and 2) shifts in recent ideas about art have impacted the way ancient art is viewed and valued.

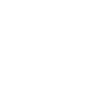

Background: Reconstruction of House E at Palenque, painted by Merle Greene Robertson.

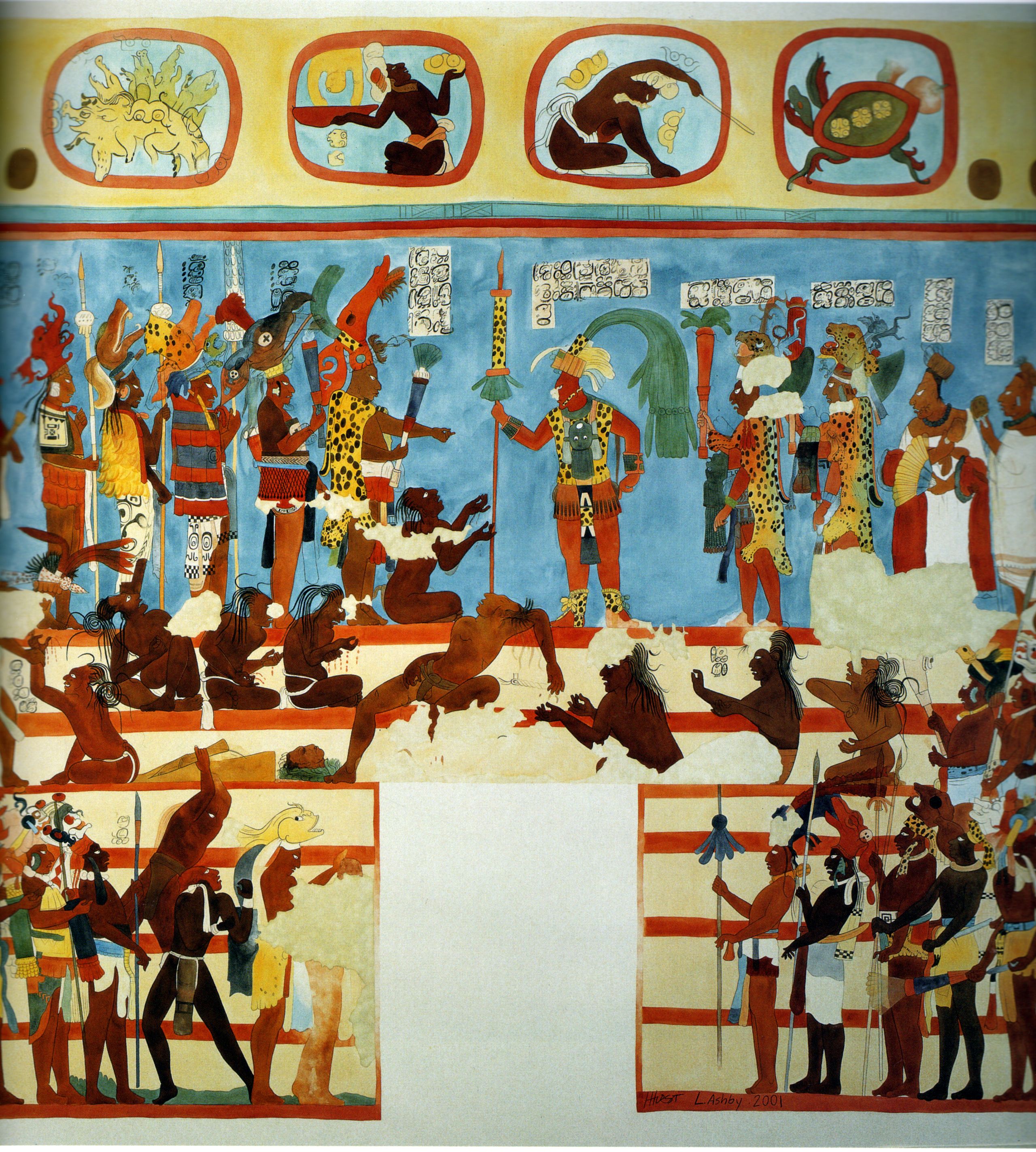

2. Heather Hurst, Leonard Ashby, Mary Pohl, and Christopher L. von Nagy, “The Artistic Practice of Cave Painting at Oxtotitlán, Guerrero, Mexico”

Although this article focuses on pictographs somewhat beyond the geographical and cultural limits of the Maya world, it provides an in-depth overview of the very specialized work that Professor Hurst does, how she does it, and how it produces new knowledge about the past, specifically the practices of image-making and how images were made.

The pictographs examined in this chapter are from the Oxtotitlán Cave in Guerrero, Mexico, first reported in the 1960s. The oldest among these paintings date to the Early Formative period (roughly 1900-1000 BCE), making them at least several centuries older than anything comparable thus far associated with the Maya. Hurst and her colleagues not only examine those images, but examine them in context—that is, in relation to the animate landscape of which they were an embedded and integral part:

"The Oxtotitlán rock art exists in a landscape rich with duality—a place that is both a recessed cave and elevated mountain, both a craggy shadowed rock surface and a relatively smooth sunlit façade. The cave is remote, natural,and wild, and yet the site is framed by plazas, terraces, and houses of Cerro Quiotepec and the cultivated fields of the river valley; it is both a place of memory, ancestors, and past things, as well as the focus of present-day conditions and the locus for intervention on behalf of the future."

View of Oxtotitlán Cave, Guerrero, Mexico (Photograph by Arnuad F. Lambert).

View of Oxtotitlán Cave, Guerrero, Mexico (Photography by Arnuad F. Lambert).

Access a PDF Hurst et al.'s Heather Hurst, “The Artistic Practice of Cave Painting at Oxtotitlán, Guerrero, Mexico” here.

As you read, pay particular attention to the techniques used by the team to gain a better understanding of the images and the ways in which they were made: note the blending of "traditional" measured drawings with the use of multispectral imaging and digital manipulation of photographs, in addition to radiometric dating techniques. What kinds of new information are gleaned from these combined approaches? Think also about the broad comparative knowledge required to interpret the paintings: how are particular details identified and understood? Why is temporality (not only with respect to dating, but also in the particular production sequences and the overall order of paintings in the cave) important in examining images and understanding the conditions under which they were made?

3. Optional: Heather Hurst, "Painting with Mittens and Bananas"

As you will have gathered from her chapter on the paintings found at Oxtotitlán Cave, Professor Heather Hurst is both an archaeologist and illustrator, known for her meticulous studies and reconstructions of Maya art, especially mural painting. In her investigations, Professor Hurst collaborates with other archaeologists, art historians, chemists, conservators, and epigraphers and employs a wide variety of imaging and analytical techniques. By focusing on the specialized processes of production responsible for the creation of painted ancient Maya artworks, Professor Hurst's research reveals not only the individual artists behind those images, but also the many decisions they made in prepping, choosing pigments, and executing their paintings. In recognition of her work, Professor Hurst was awarded a Macarthur Fellowship (unofficially known as a "Genius Grant") in 2004.

For more information on our guest and some of her earlier work documenting the Preclassic Maya murals at the site of San Bartolo (referenced in the assigned chapter above), you can watch the TEDx talk, "Painting with Mittens and Bananas," given by Professor Hurst at Skidmore College in 2013.

4. Mary F. McVicker, “Teopancaxco: The Art of Recording the Ruins,” “Chichén Itzá,” “Life Begins at Fifty,” “The Extraordinary Undertaking: The Murals in the Upper Temple of the Jaguars,” and “Color Plates”

Background: Painting of the Annex of the Casa de las Monjas at Chichen Itza by Adela Breton.

These selections come from Mary McVicker's biography of Adela Breton, a truly remarkable late 19th/early 20th-century artist. Born in London in 1849 and raised in Bath, Breton first traveled to the ruins of Chichen Itza in 1900—begining her career as an archaeological illustrator at the age of fifty! Breton, who never married, began traveling throughout Canada, the United States, and Mexico after her father passed away in 1887. Although it was not wholly unusual for a certain type of Victorian woman (unmarried, without family obligations, financially independent, and in search of a degree of freedom and choice unavailable to them in England) to "explore" as Breton did, she stands apart in her self-appointed mission to study and document ancient American art, artifacts, and ruins. She visited Teotihuacan in 1894, just around the time that a remarkable set of murals were uncovered in a small house site, Teopancaxco. Breton made color copies of those murals, seemingly only to satisfy her own interests in archaeology and antiquities. Her impromptu drawings remain the best record of the paintings, which were later destroyed by exposure to the elements.

Access a PDF of selections from Mary McVicker's Adela Breton: A Victorian Artist Amid Mexico's Ruins here.

Background: Copy of a wall painting from the outer chamber at Teopancaxco made by Adela Breton (from her notes, it is likely a copy of a copy).

Background: Detail from Adela Breton's full-size copy of the "Pulque Priests" wall painting at Teopancaxco.

As you may by now expect from this course, familiar names appear in Adela Breton's story: Augustus and Alice Le Plongeon from Week 1 and Alfred Maudslay, about whom you will read in detail below. Possibly through other artists and copyists in London, Breton was connected to Maudslay and offered to visit Chichen Itza for him in order to check his drawings and to accurately document the murals of the Upper Temple of the Jaguars.

The importance of Adela Breton's work lies not only in what she did—replicating ancient artworks in painstaking detail—but in the timing of when she did it. Many of the frescoes and murals documented by Breton were recently uncovered when she copied them. Painted stucco and bas reliefs are fragile and erode and damage quickly. Today, some of the copies Breton are the only records of the details and colors of irreplaceable ancient images that have been lost to time.

5. See more of Adela Breton's work through the Visual Resource Center's collection here (requires UChicago login).

As you read, ask yourself how Breton fits into or breaks the mold of other 19th-century amateur experts and explorers whose work has been recognized as foundational to Maya archaeology. Consider Breton's work in relation to Professor Hurst's at Oxtotitlán: what is similar or different about the approaches, the questions motivating them, and their results?

Background: Adela Breton's copy of a portion of the murals in the Upper Temple of the Jaguars at Chichen Itza.

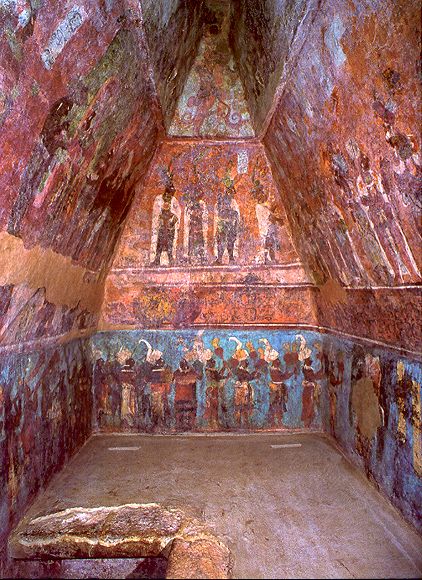

6. Ian Graham, “Tatiana Proskouriakoff: 1909-1985”

Like Adela Breton before her, Tatiana (Tania) Proskouriakoff's story involves a combination of talent, intellect, independence, and serendipity. Proskouriakoff finished her training in architecture in 1930 (the only woman in her class), just as the Great Depression began. With no job prospects, she became a designer for a needlepoint studio, copying and reducing drawings so that they could serve as patterns. Prokouriakoff began visiting the University Museum at the University of Pennsylvania to copy items for her needlepoint designs. While there, she volunteered to produce drawings for the Classics Department in exchange for library access. Her drawings caught the attention of Linton Satterthwaite, who was overseeing UPenn's expedition to Piedras Negras, Guatemala. Satterthwaite invited Proskouriakoff to join the team (without pay).

Background: Reconstruction of the Acropolis of Piedras Negras by Tatiana Proskouriakoff

Proskouriakoff's work at Piedras Negras was shown to Sylvanus Morley during one of his visits to the University Museum, who contracted her to travel (alone) to Copan in 1939 and produce a series of architectural reconstructions. There, Proskouriakoff worked under the CIW direct, Gustav Stromsvik. Proskouriakoff was, at times, at odds with Stromsvik, arguing over architectural elements and critical of the CIW restorations of Copan's Hieroglyphic Stairway (Prokouriakoff's insights were usually later proven correct). Paid for her work for the first time, Proskouriakoff earned $500 for the season at Copan.

With funding provided by Morley, Proskouriakoff visited, participated in excavations at, and produced drawings of a number of ancient Maya cities. Her reconstructions were published by the Carnegie Institution as An Album of Maya Architecture in 1946 (you saw some of those images—of Uaxactun—in the "Big Digs" Shorthand page).

Background: Reconstruction of Stela M and Temple 26 (the Hieroglyphic Stairway) at Copan by Tatiana Proskouriakoff.

7. See more of Tatiana Proskouriakoff's work through the Visual Resource Center's collection here (requires UChicago login).

Optional: You can also view a complete digital version of Proskouriakoff's An Album of Maya Architecture through the temporary emergency access being provided by the HathiTrust, here (requires UChicago login).

Background: Reconstruction of the city of Chichen Itza, viewed from the north, by Tatiana Proskouriakoff.

Although Proskouriakoff is perhaps best known for her architectural renderings, she also played an important role in the process of decipherment. After her travels and documentation work for the CIW, Proskouriakoff was hired as a full-time staff member at the CIW's headquarters near the Peabody Museum in Cambridge, MA. She participated in the CIW's final large-scale excavations at Mayapan and was able to remain at the Peabody Museum after the dissolution of the CIW's Division of Historical Research (discussed in Ed Shooks "Recollections" for October 13). At the Peabody, Proskouriakoff turned her meticulous attention to Maya monuments and hieroglyphic writing. First, Proskouriakoff produced A Study of Classic Maya Sculpture, in which she analyzed roughly 400 monuments to produce a method for dating Maya sculpture on the basis of sculptural form and style, with a resolution of about 20-30 years.

Soon after, Proskouriakoff discovered what she called "a peculiar pattern of dates" in the stelae of Piedras Negras. The dates on the monuments, she noted, aligned with human life cycles: births, accessions to power, deaths. In a short paper that followed, Proskouriakoff proposed that monumental inscriptions, long thought to contain only calendrical dates, prophecies, and accounts of astronomical events, actually recorded the lives (and therefore, history) of individual Maya rulers (you will hear more about this moment next week when we focus on Maya writing). As Michael Coe described it:

"In one brilliant stroke, this extraordinary woman had cut the Gordian knot of Maya epigraphy, and opened up a world of dynastic rivalry, royal marriages, taking of captives, and all the other elite doings which have held the attention of kingdoms around the world since the remotest antiquity. The Maya had become real human beings."

Access a PDF of Ian Graham's obituary, “Tatiana Proskouriakoff: 1909-1985” here.

As you read, think about Proskouriakoff's unique combination of skills, access to archaeological sites and artifacts, and insights into Maya monumental art and writing. How do those various threads of her experience connect to one another? Do you think her important conclusions about Maya sculptural style and hieroglyphic writing would have been possible without her artistic talent, architectural training, and eye for detail? More broadly, what have been the impact of artists and illustrators (notably, often women) on the field?

8. Barbara W. Fash, “Beyond the Naked Eye: Multidimensionality of Sculpture in Archaeological Illustration”

In this chapter, Barbara Fash, director of the Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions (CMHI) Program (about which you will learn more next week), discusses the shift from "traditional" forms of archaeological illustration to technology-assisted forms of documentation. Fash describes the CMHI's ongoing efforts to document, replicate, and, at times, rearticulate or reproduce the sculpture of Copan, Honduras. Fash demonstrates not only how drawing, photography, and three-dimensional scanning are all critical elements in current studies of Maya monumental art, architecture, and inscriptions, but also how training in those diverse methods is essential to accurate documentation.

In particular, Fash highlights the work of Alexandre Tokovinine, an epigrapher and professor at the University of Alabama (one of Tokovinine's interactive 3D models from Copan can be found to the right). Tokovinine's own artistic skills and literacy in Maya hieroglyphs is key to the ease and success of the CMHI's scanning efforts. As Professor Hurst's work at Oxtotitlán has likewise already shown us, it is the combination of a diverse range of techniques, involving various special skills, that is most effective, rather than any one approach used in isolation.

Access a PDF of Barbara W. Fash's, “Beyond the Naked Eye: Multidimensionality of Sculpture in Archaeological Illustration” here.

As you read Fash's chapter, think about the developing role of technology in the study of images, image-making processes, and preservation. How do the results of the various techniques available (line drawings, photographs, 3D scans) differ? Which do you find most accurate, intelligible, informative, and/or aesthetically pleasing? At one point, Fash makes an analogy between archaeological artists or illustrators and surgeon and "the interjection of technologies between their hands and eyes" (p. 461). What do you think about this analogy? Can you think of other analogous situations in which "traditional" techniques are complemented or replaced by new technologies? What are some of the new challenges technologies bring to the table?

8. Jago Cooper, “Preserving Maya Heritage with the British Museum”

The British Museum holds a large collection of casts of Maya monuments made by Alfred Maudslay (whose name you'll recognize from Adela Breton's biography), including copies of sculptures at Yaxchilan and Copan from the 19th century. The British Museum has recently joined forces with Google Arts & Culture to not only digitize Maudslay's casts, images, and notes, but also to scan new monuments and architecture and to combine those with 360-degree virtual tours, building entire digital worlds from ancient Maya archaeological sites and artifacts.

In addition to the overview video below, visit the Google Arts & Culture "Exploring the Maya World" page here.

Based on our readings and discussions for this and earlier weeks, what do you think of the collaboration between the British Museum and Google Arts & Culture? What are its successes and what are its shortcomings? Is this (or should this be) the way forward in terms of cultural preservation and knowledge dissemination? Why or why not?