The Role of Maya Women

From the Classic Era to the Post-Civil War Period

Introduction

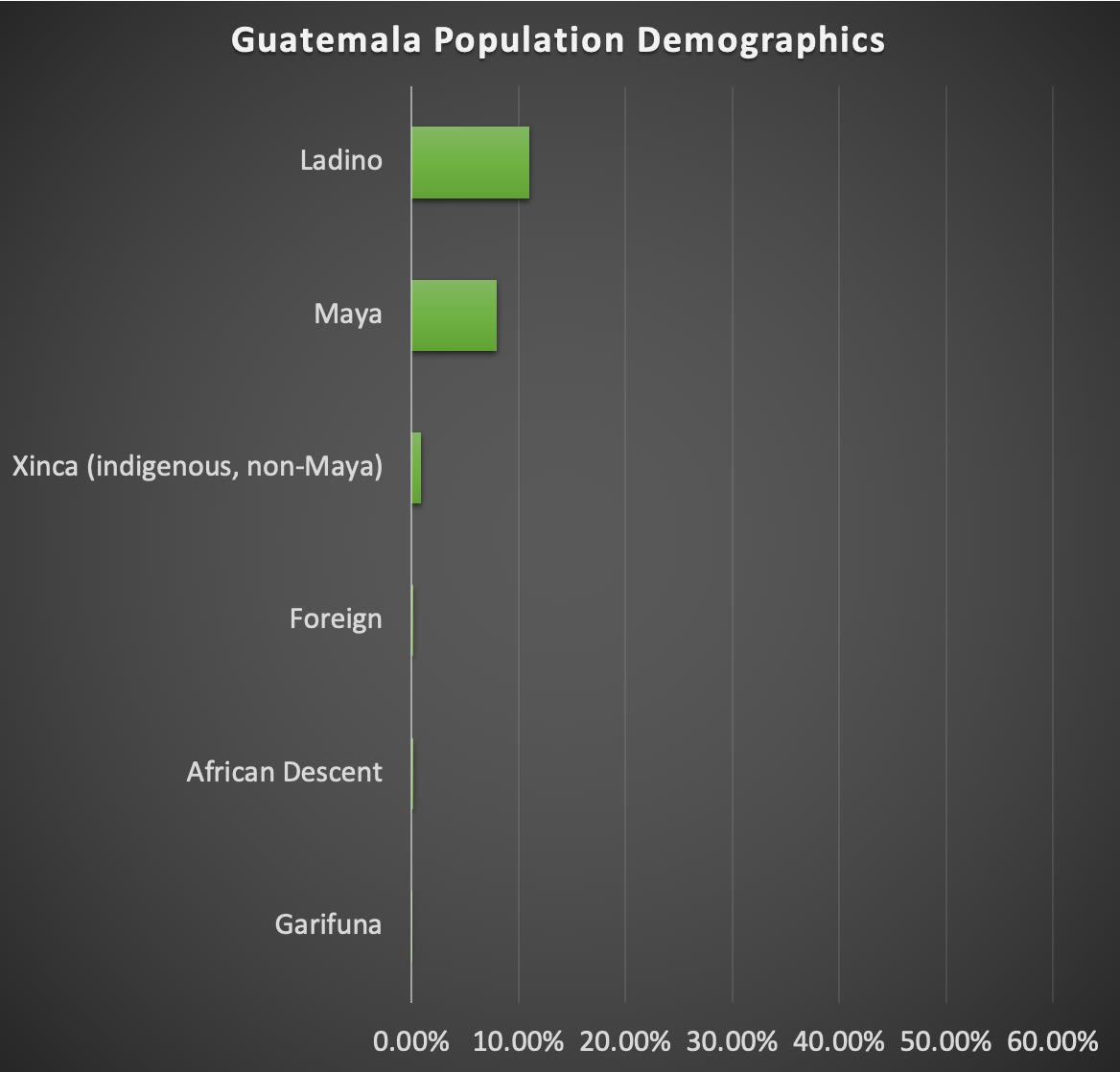

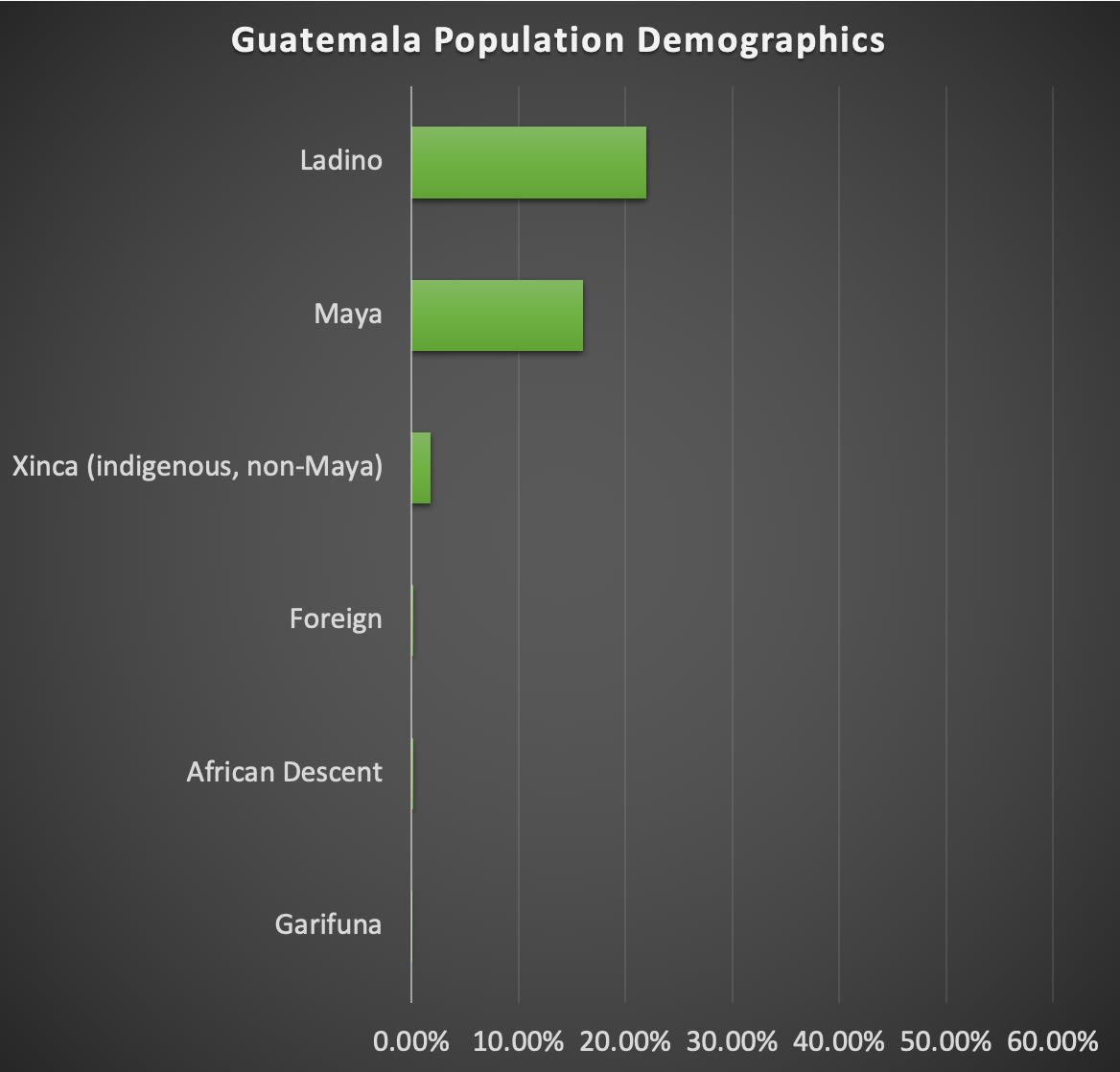

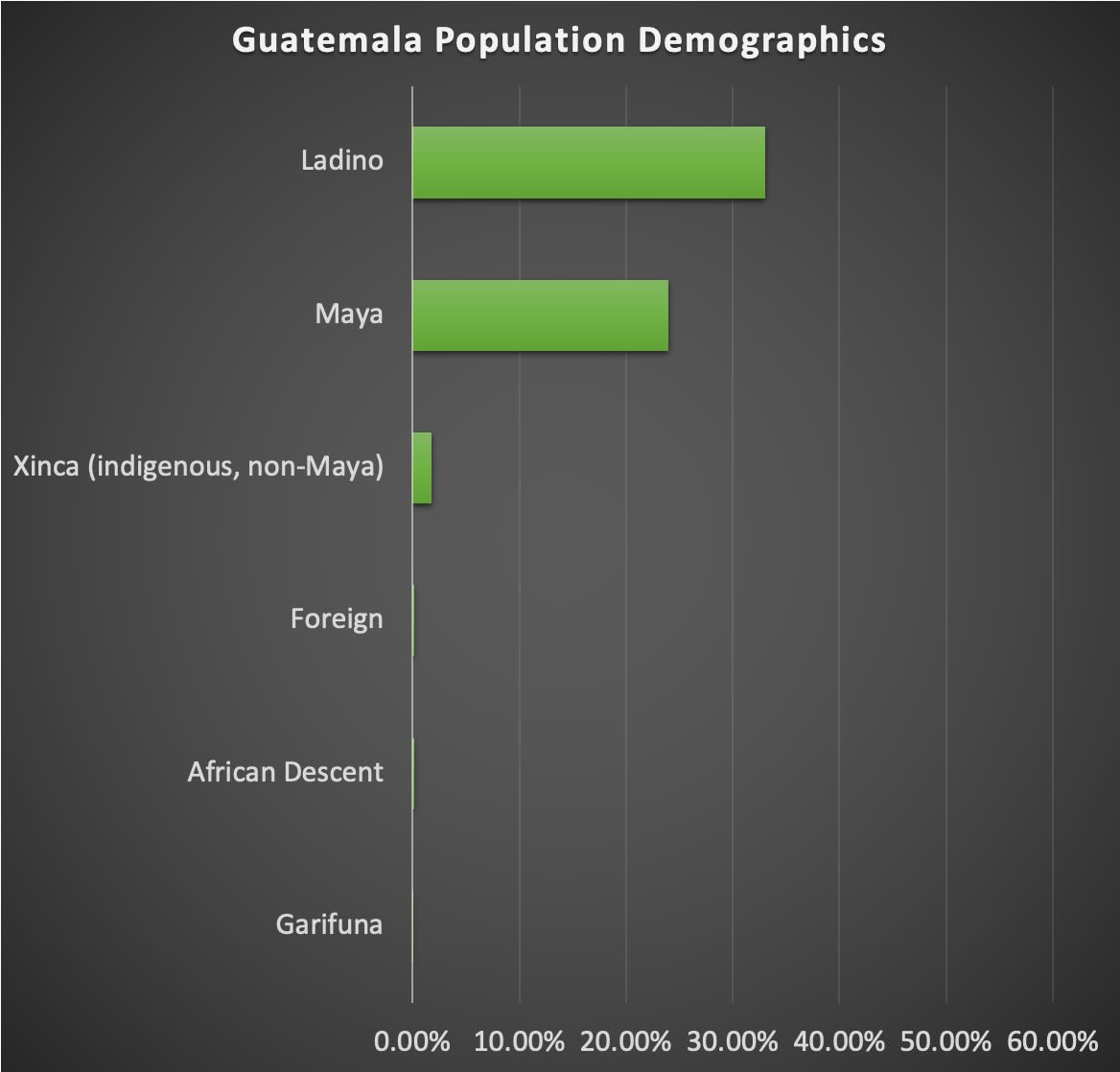

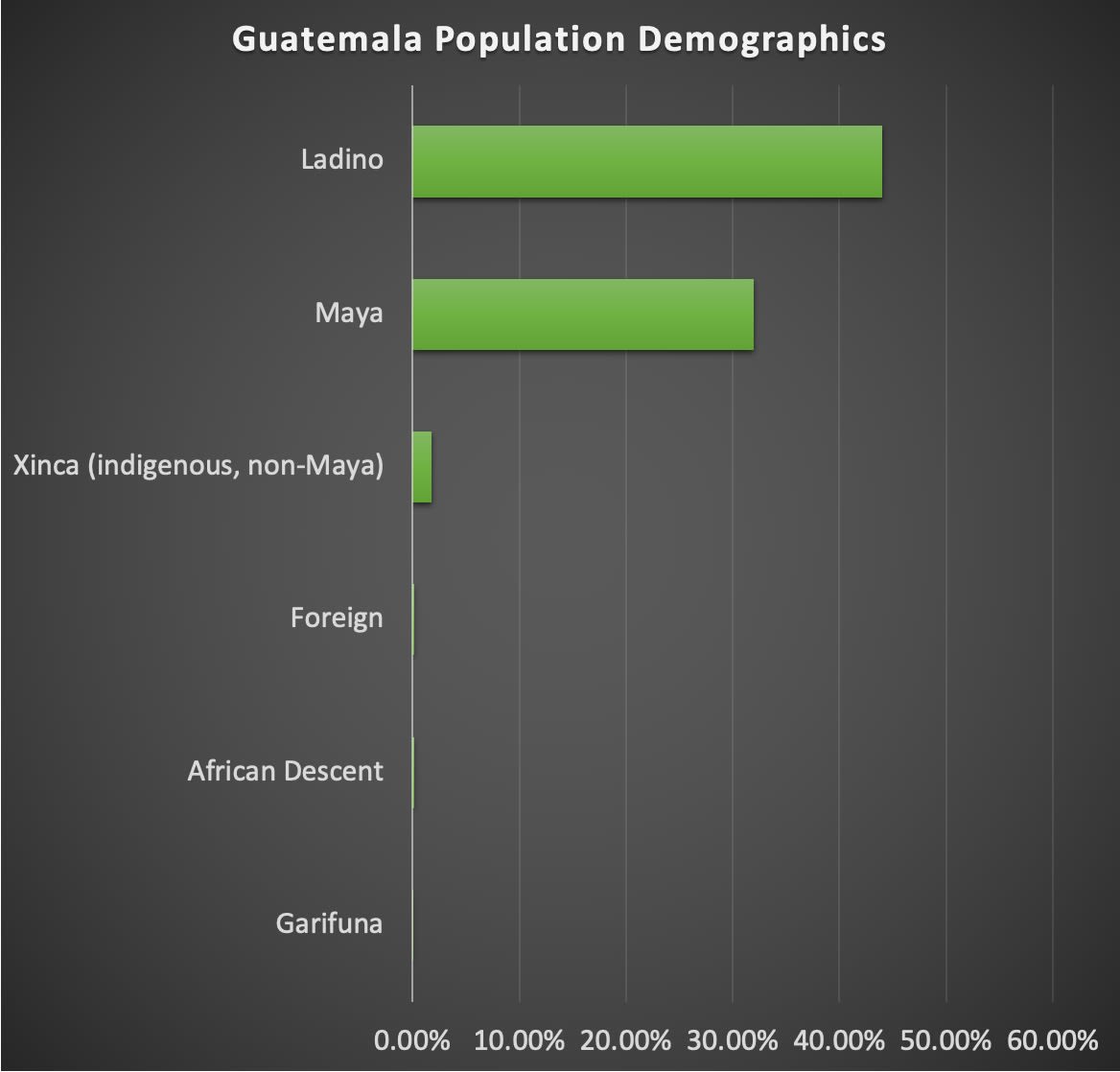

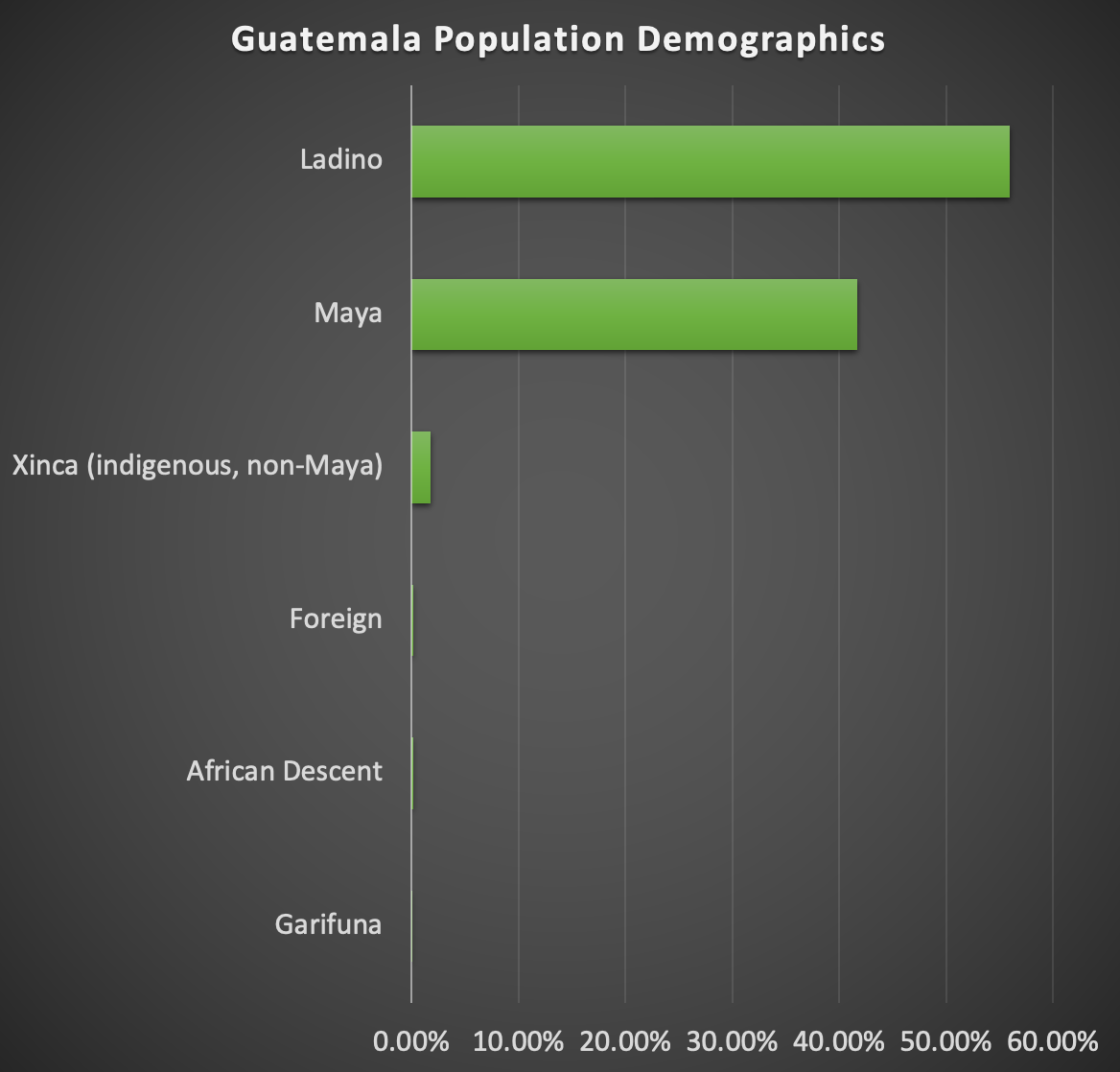

The Maya were an extremely complex as well as expansive civilization that occupied most of Central America for centuries. There are still a lot of things that archaeologists and anthropologists have yet to discover and understand, but with the advances in technology and research methods, new pieces of information are uncovered every day. One of the most impressive things about the Maya that distinguishes them from other ancient civilizations is that their heritage and descendants are still present in the Mesoamerican region. Maya communities make up around 51% of Guatemala's population and practice around 26 different indigenous, Mayan languages.1 Ever since the Spanish invasion, the Maya have been sudjected to continuous persecution and massacre. In modern times, they have struggled for decades to be recognized by the Guatemalan government and to recieve the same treatment and rights as other guatemalan citizens.

"That is, most of the time it is probably the same old story: the men stand out in front in the funny costumes; the women just tell their husbands and sons what to do from behind the scenes. But not all the time." ~Kathryn Josserand, "Ancient Maya Women"

One group within Maya communities which have had their idenpendent experiences throughout all of these tribulations are the women. Maya Women could arguably be considered some of the most affected groups among the Maya with their own set of stories and experiences to share. In the following sections, we'll be focusing on how women from the Guatemalan Maya communities have been been portrayed from the Classic Era to Modern Times. We'll especially take into consideration the impacts the Guatemalan Civil War and the repurcussions it has had on the Maya female community.

The Classic Era

Overview

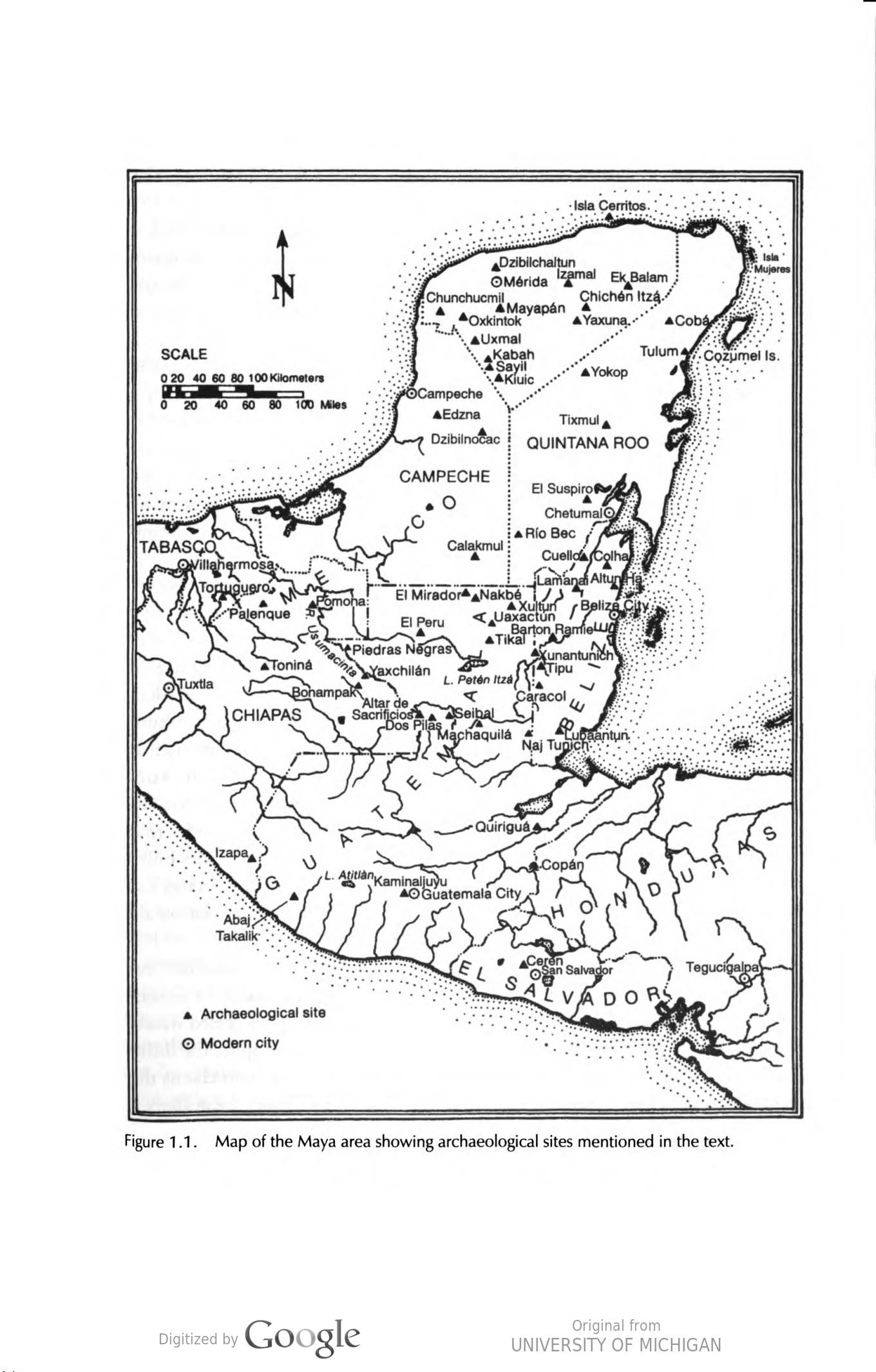

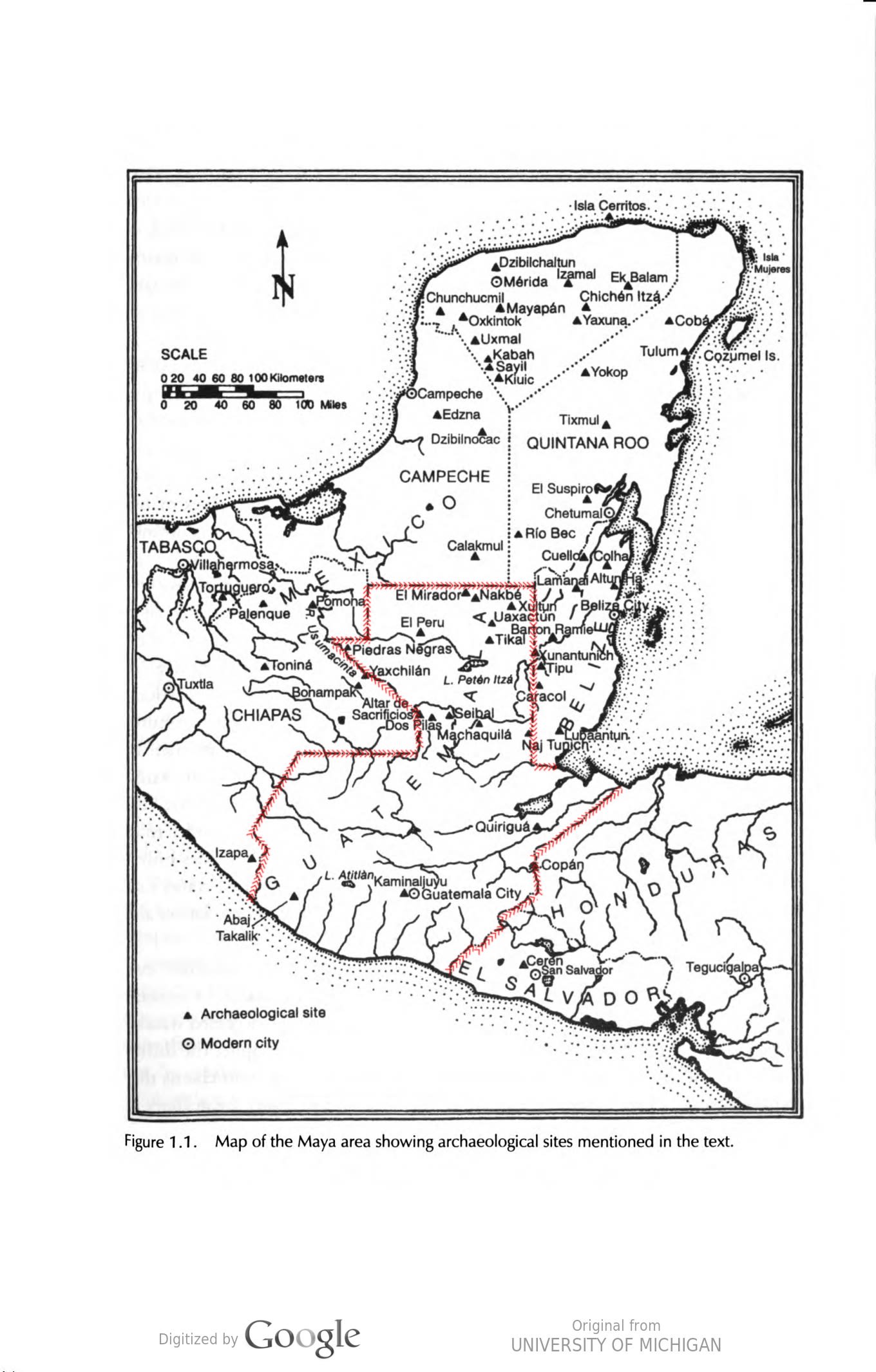

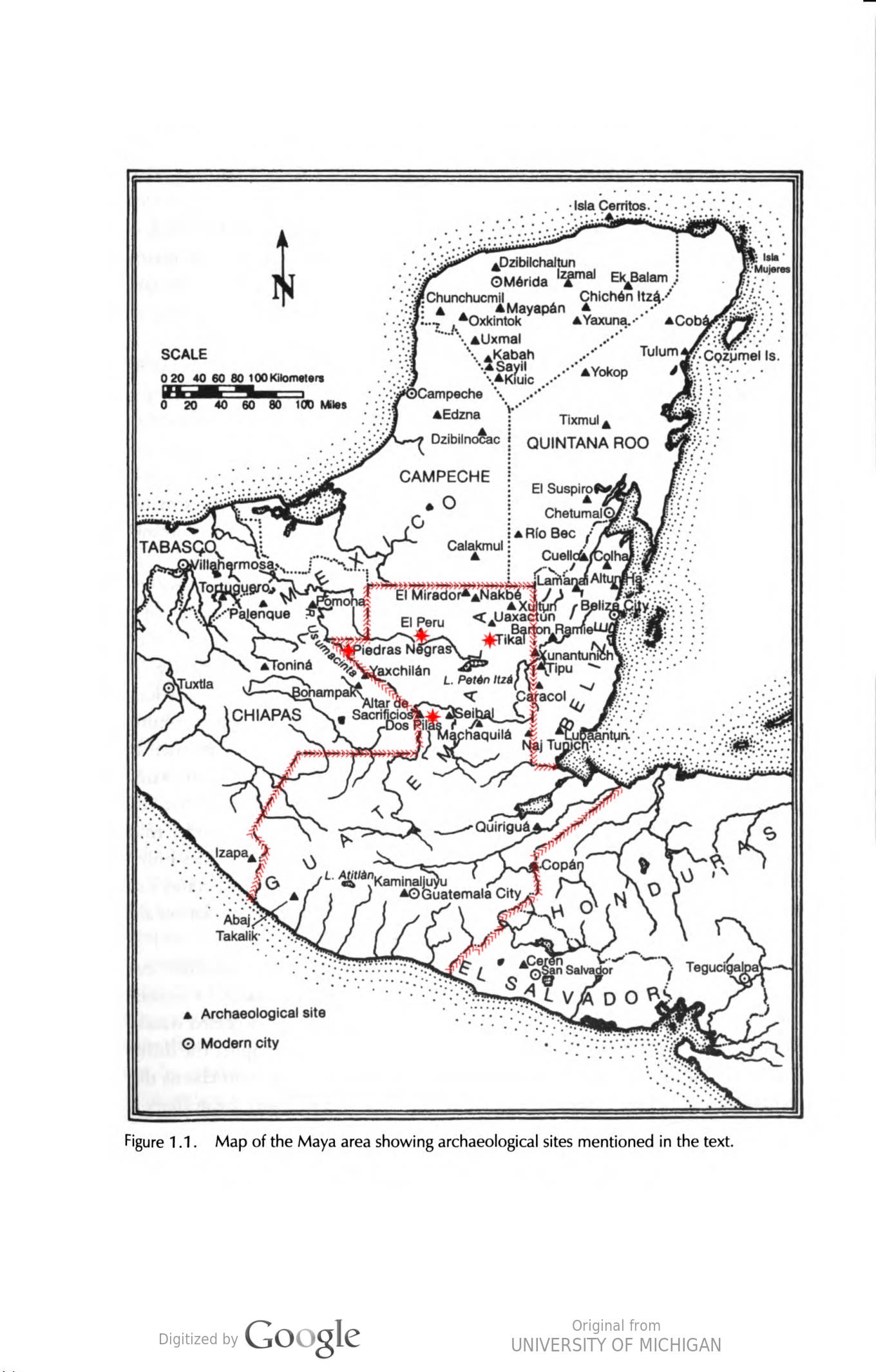

The Maya are considered to be one of the most complex civilizations in ancient history. They’ve gone through countless transformations and are still present in some regions of Central America. Their expansive territory traverses many countries including Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honaduras, and El Salvador. Archaeological evidence has dated their origins all the way back to 7000 BCE. With so much history ingrained in the little remains we have of this great ancient civilization, it has taken a lot of time for archaeologists to interpret the evidence and piece together the realities of the Maya ancestors. One of these realities is the concept of gender and gender roles within the Maya community, especially during the Classic Era. The Classic Era has proven to be one of the main sources for collecting evidence about the Ancient Maya as a whole. Most of the modern day Maya are located in Guatemala. For this reason, we’re going to be evaluating the role of women within past and present Maya communities in Guatemala.

The Classic Period is considered the time when Maya civilization reached its peak with their most advanzed astronomical, architectural, mathematical, and artistic creations dating back to this era.1 Some of the most important sites for compiling a corpus that can attest to the role of Maya women during the Classic Era are Naranjo, Tikal, Dos Pilas, and El Perú. When studying ancient Mayan women in Guatemala, most of the archaeological evidence can be divided into two categories: artwork/image representations and hieroglyphic texts. A lot of the information archaeologists have gathered on women's role within this ancient society comes from the artwork found in large monumental structures as well as remains of household ceramics. It is important to understand that, despite scholars deciphering more and more details about this ancient civilization every day, the mentioning of Maya women is very limited compared to that of men. In reality, most of the information available on the role of ancient Maya women is centered around women belonging to the elite class or royalty. For this reason, most of the conclusions that will be presented in the following sections are solely based on the interpretations that have been made about powerful women during the Classic Period.

* Original map from "Ancient Maya Women" by Traci Arden (Fig.1.1). This map delineates the boundaries between Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras and emphasizes the sites in Guatemala most relevant to the topic. *

The Bonampak Murals

One of the first archaeologists to talk about the role of women within Maya society was Tatiana Proskouriakoff in her essay “Portraits of Women in Maya Art.” Here Proskouriakoff lists all of the different features she believes most typically distinguish women in Maya art. One of the most predominant features were the costumes that women wore across the different scenes. The huipil, a tunic that was worn underneath skirts and any other clothing, was one of the most common pieces of garment used by women in their artistic representations. In fact, it was not uncommon to see males also using a huipil for certain religious ceremonies.1 This brings into discussion the very interesting topic of gender ambiguity in Classic Maya society, which raises the question of did the Maya have a perception of gender completely different to the one we originally thought they had?

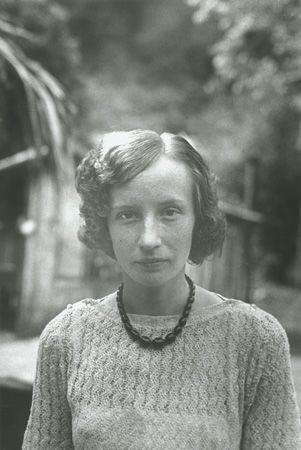

*Tatiana Proskouriakoff (August 1985; Penn Museum Image #37401*

The answer to that is yes. Signs that the Maya didn’t really see gender in the way we expected have been present in even the earliest of archaeological evidence. One of the most significant of them being the Bonampak Murals. In Proskoriakoff’s essay, her interpretation of some of the scenes from these murals provide insight into Maya gender roles during the Classic Era. For example, the murals show scenes of women carrying out various activities that would have been traditionally reserved for men, such as bloodletting rituals, seating in thrones and helping in the prosecution of prisoners.1 In her essay, Prosloriakoff said, “It's hard to determine the sex of robed figures especially in monumental art where sexual characteristics of the feminine figure are invariably suppressed.” This is struggle that has been encountered by many scholars who try to differentiate what practices and traditions were respective to women and which ones were for men.

*Bonampak; Murals, Room 1; Photgraph by Linda Schele; Schele #: 79005, 79007*

The Third Gender

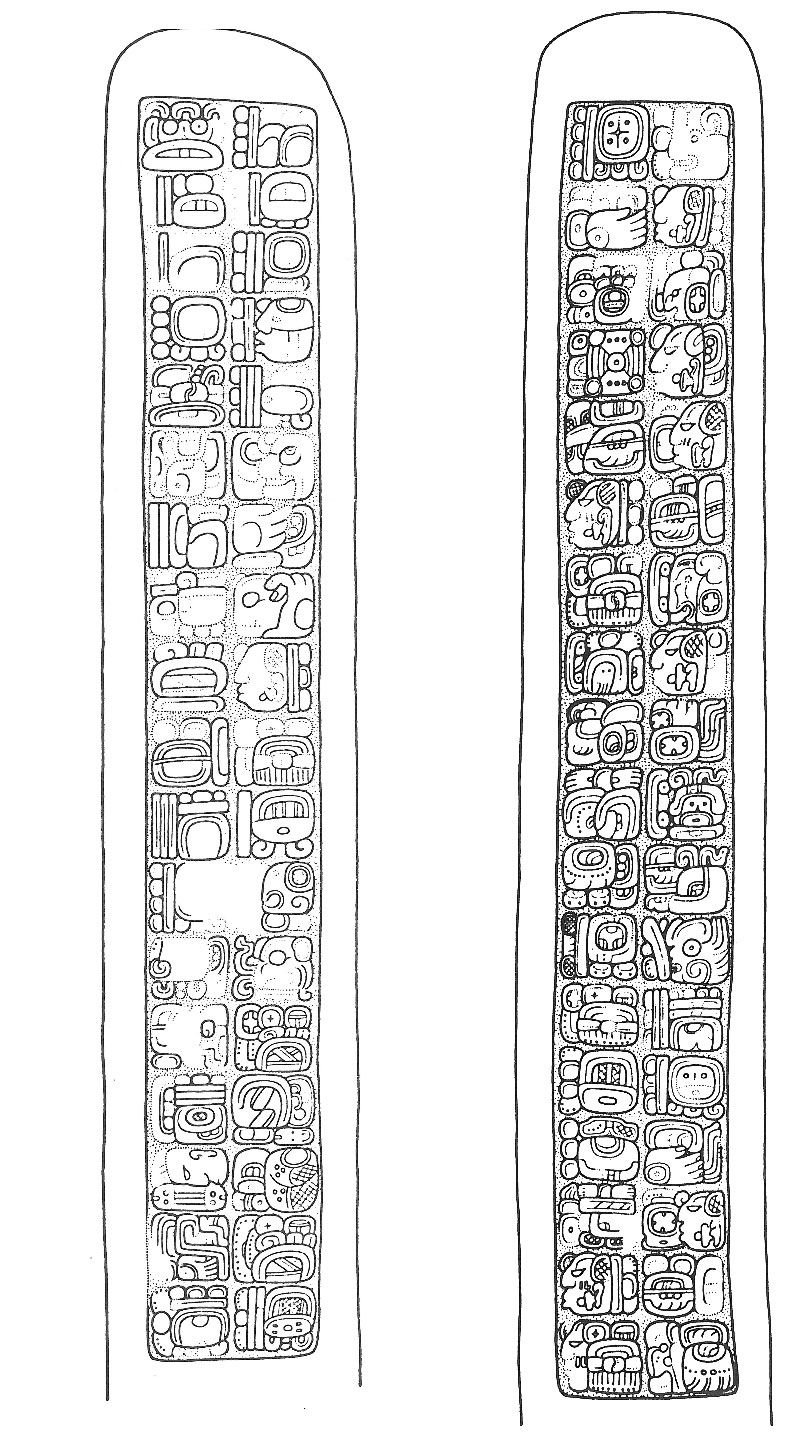

In his essay on the “third gender” within Maya culture, Mathew Looper said, “many images of Maya rulers negotiate a fluid mixed-gender realm which afforded multiple alternatives to polarized ‘male’ or ‘female’ identities.”1 In this case, Looper is introducing the practice among the ancient Maya rulers to adopt different costumes (either traditionally male or female) in order to achieve certain religious and image purposes. For example, one of the most revered deities was that of the pairing of the Maize god and Mood goddess. This figure was typically depicted with both female and male characteristics. This, in turn, prompted different rules to wear costumes that wear also mixed-gender in order to convey the same supernatural and spiritual essence.2 Another example can be seen in ceremonies such as the Period-Ending rituals where male rulers would sometimes wear female costumes or use already determined attire which included skirts and capes. These styled costumes were for both men and women and were at times hard to distinguish.3 This gender ambiguity that could sometimes be seen in religious ceremonies and in commemorative monuments not only hints at the complex gender perception the Maya had but also at the, at times, complementary roles that existed between men and women.

*Stela 16, Tikal; Walwin Barr, University of Pennsylvania Tikal Project Negative C57-8-68, All rights reserved. University of Pennsylvania Museum; Shows Hasaw Kan K'awil wearing a ritual dress for a Period-Ending ceremony*

Gender Relations

Women for the most part are depicted with being in charge of taking care of daily household tasks such as cooking and textile production. However, some scholars have interpreted these tasks as being complementary to those of men. When describing this complementary relationship, Rosemary Joyce says that "women's labor transforms the raw materials produced by men into useful products crucial to social, ritual, and political process." What she means is that if it weren't for the work of the women, men wouldn't have the material means requiered for religious ceremonies as well as every day life. The same goes for women whom without men's labor wouldn't have the necessary materials to produce food, textiles, and other ritualistic offerings.1 Another quote that explains this concept of complementarity is seen in Josserand’s essay, “Women in Classic Maya Hieroglyphic Texts,” where she says, “males may perform most publicly viewed activities, but they cannot serve in office without wives to perform other rituals offstage and to organize less public ceremonies from maintaining a household altar to the saint for the year of office to producing the all-important ritual meals of Maya ceremonial life.”2 This demonstrates the importance of women in every-day rituals and how essential females are for Maya society as a whole to go forward.

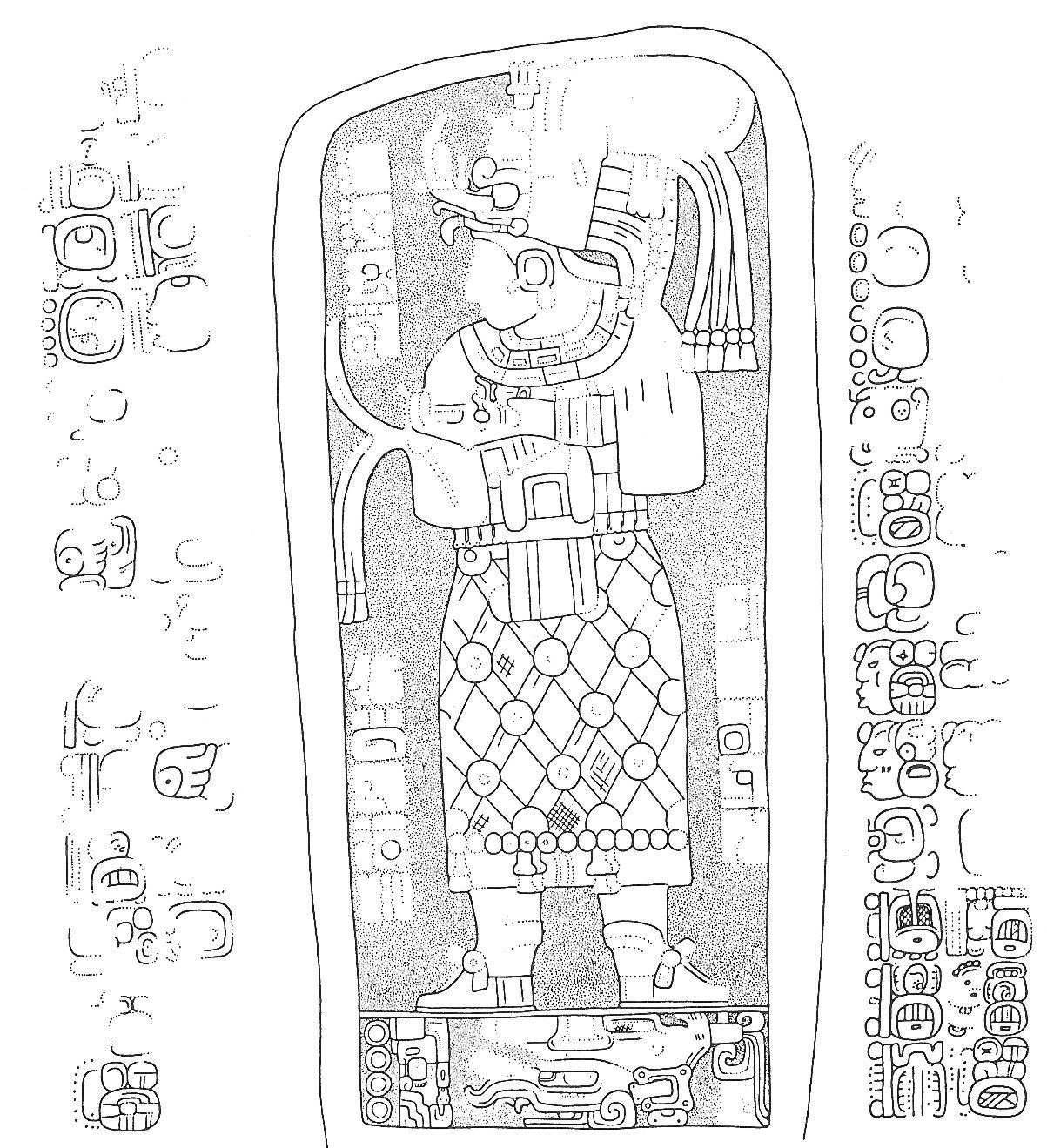

*Stela 24, Naranjo; Image from L. Schele And D. Freidel, A Forest Of Kings: The Untold Story Of The Ancient Maya 1990:187, Fig. 5:13; Stela narrates the arrival of Lady Six Sky in Naranjo and the birth of her son. This marks the start of a new legacy in Naranjo which saved it from the percieved ruin it was facing*

During the Classic Period, there was an increase in the role of women in different ceremonies and rites. There is also evidence of women gaining more importance among the upper class with more burials and monuments being dedicated to them.3 This didn’t occur in great abundance, but it was enough to notice a shift in the importance that was being given to women in society. This is mainly due to the fact that during the Classic Period many kingdoms were reaching their peak of development, bringing forth a rise in powerful secular rulers. In exchange, this also brought forth a mindset where women were extremely important in securing alliances and continuing the ruling families’ dynasties.4

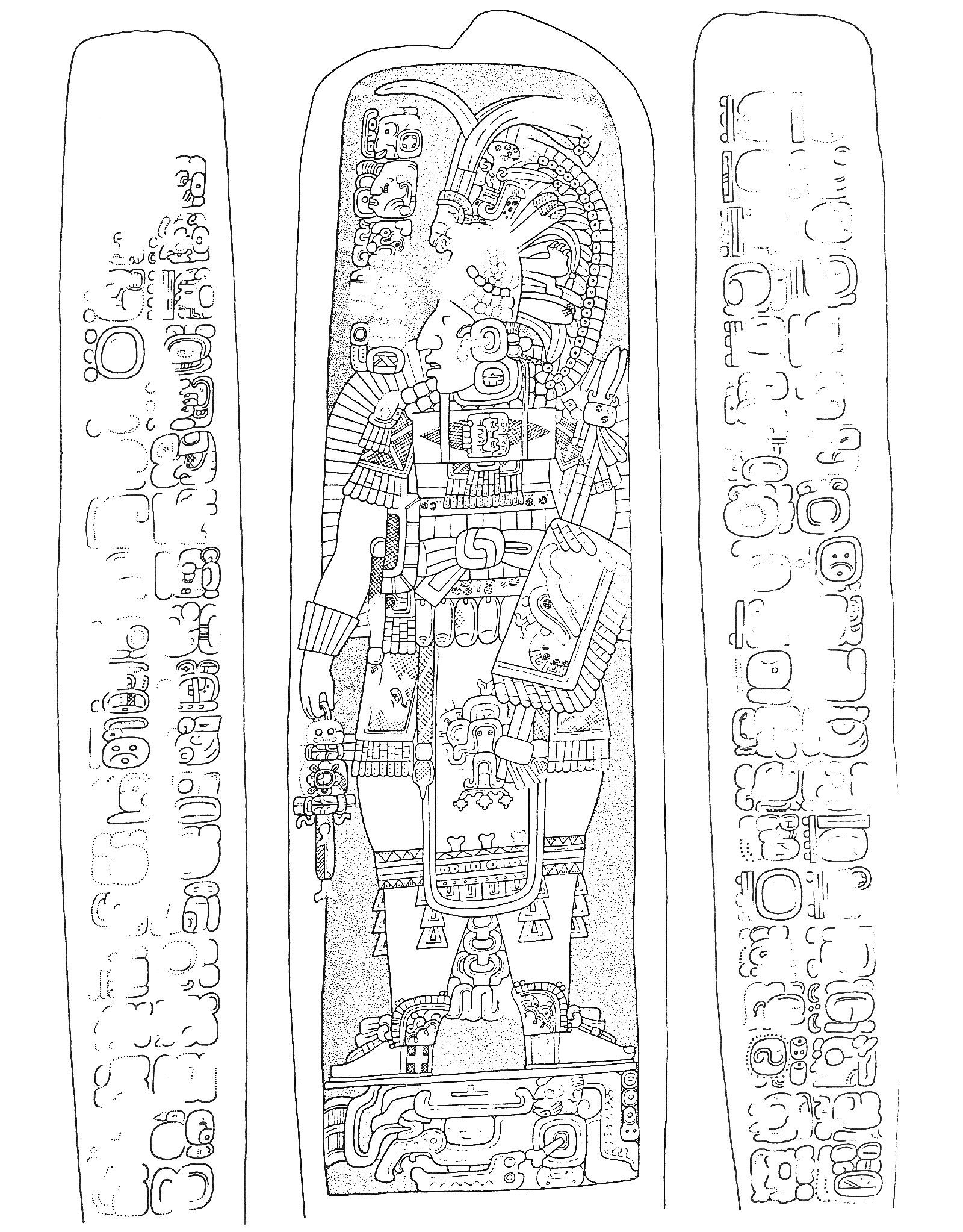

*Stela 3, Naranjo; Image from L. Schele And D. Freidel, A Forest Of Kings: The Untold Story Of The Ancient Maya 1990:193, Fig. 5:18; Shows Lady Six Sky participating in her son's anniversary ceremony*

Something that most scholars who have written about this topic agree on is that lineage and kinship are one of the most important parts of women’s relevance in the upper class. There is countless evidence that demonstrate examples of women passing down the right to rule to their husbands and sons.5 In fact, as Josserand said in her essay, “in the maya world…for purposes of succession it is more important to be the child of the previous ruler than it is to be the male.”6 This means that, regardless of their gender, Maya princesses carried a lot of purely inherited power which was purely inherited. In other words, these women were born with the right to rule and it is they who give the men in their lives the authority to rule. In the following sections we’ll see some examples of women who, despite the tradition of letting the men rule, took advantage of their birthright and ruled as some of the most notorious queens in Maya history.

It’s impossible to say with absolute certainty how these women felt about their roles or what realities they were facing that were not included in the pieces of evidence that we have. However, it is fair to assume that they were respected enough and considered important enough to have all sorts of monuments erected in their honor. Whether it was stelae, massive murals, or clay figurines, Maya women during the Classic Era had clearly become an important asset for the progress of the society as a whole. In fact, we can go even further and identify three important Maya women from the now Guatemala region, that have been found to carry great importance in the history of this ancient civilization.

*Stela 2, Naranjo; Image from L. Schele And D. Freidel, A Forest Of Kings: The Untold Story Of The Ancient Maya 1990:192, Fig. 5:17; Shows Smoking-Squirrel celebrating a Period-Ending Ceremony*

Women in Figures of Power

Throughout the excavations that have taken place over the last couple of decades, archaeologists have been able to identify three important Maya Queens whose stories were not the ones typically seen regarding Maya women in power. It is not common to find stories where women are the protagonists and, for this reasoning, each uncovering reshaped the understanading of Maya society. The three Maya Queens we’ll be studying more in detail are Lady Six Sky (Wak Chanil Ahau) of Naranjo, Lady of Tikal, and Lady K'abel.

The Lady of Tikal

The Lady of Tikal has been regarded as one of the most important queens in the history of Tikal. She makes an appearance in several stelae from the site including Stela 6, 12, and 23. As epigraphers deciphered the texts in this stelae, they learned that the Lady of Tikal is daughter of Tikal’s 18th ruler, King Chak Tok Ich’aak II, who died when the young princess was only four years old. The Lady of Tikal, whose real name has still not been confirmed, came into power at seven years old in the year AD 511.1 She is understood to have ruled for around 16 years, but not alone. Interestingly enough, the young Queen is mentioned in Stela 12 along with, what scholars assume to be, a regent or consort named Kalomte’ Balam. Kalomte’ Balam is addressed as the 19th ruler of Tikal.2 It is unclear if this means that he was her husband, a family, or her son, but what should be noticed about this rare situation is that the power that this ruler has comes directly from his connection to the Lady of Tikal. It is through her that he achieved this position of power.

Lady Six Sky of Naranjo

Lady Wan Kan Ahaw was a young princess from the powerful kingdom of Dos Pilas who was sent to the lesser kingdom of Naranjo in order to revitalize the power of the royal family.1 It is unclear why she was the one chosen for this task instead of a second son or another male in the family. However, when evaluating the situation from the lenses of royal Maya women being extremely important for passing down lineage and power, it makes sense why sending the king’s daughter was a strategic move. It is clear that Lady Six Sky was successful in pushing Naranjo towards the right direction and that insinuates that, despite her being a female ruler, she was able to assert her power amongst the people. However, this interpretation can also be questioned by the fact that, when her son turned 5, he was declared the king of Naranjo. There’s no explanation as to why this happened, but it is understood that besides her son now being ruler, Lady Six Sky was still the one making all of the major decisions. In fact, she’s attributed the victory in a military campaign against Ucanal and Yaxhá as is depicted in Stela 24.2 The queen is also seen in Stela 31 where she’s wearing a costume that symbolizes and legitimizes her royal status. This stela was erected during her time as ruler which demonstrates that she had immense power and control over land resources and labor personal in order to be able to build a monument in her own honor.

Lady K'abel

Lady K’abel ruled the Wak kindom, now known as the site of El Perú-Waka’, alongside her husband from around AD 672 to AD 692.1 In 2012, an archaeologist from Washington University in St. Louis named David Freidel claimed that they had found the great queen’s tomb. This was later confirmed by other archaeologists who agreed that the evidence corresponded to the late Queen K’abel. Lady K’abel is another great example of women rulers who were exerting their birthright to rule. She was tasked by her parents, the queen and king of the great city of Calakmul and descendants the infamous “Snake” dynasty, to rule over the Wak Kingdom while they remained in the in the capital.2 An interesting fact that distinguishes Lady K’abel from other Maya queens is that she is often depicted with military artifacts such as battle shields. This has resulted in her being known as the “warrior queen.”3

Check out this short interview of archaeologist David Freidel who led the excavations in El Perú-Waka where the suspected tomb of Lady K'abel was found!

Up until now, we’ve seen in detail how Maya women were portrayed during the Classic Period. Based on these depictions we are able to draw conclusions as to what their role might have within the society as a whole. However, despite Maya gender roles defying the original expectations of archaeologists, it is important to understand that that does not directly correlate to Maya women having an equal standing to men. It also should not be interpreted as Maya women being better off during the Classic Era rather than in the Contemporary Era. In both cases, Maya women have struggled to have any agency in the stories being told, especially their own.

As we previously saw, there are not many women figures of power that have been recorded in archaeological texts. If anything, for the past couple of decades, scholars have been reusing the same queens and depictions of females in order to further their studies on ancient Maya gender norms. This lack of female voices during the Classic Era is still prevalent nowadays in Guatemala. In the following sections, we’ll discuss certain key events, such as the Guatemalan Civil War that have transformed the modern Maya women experience as well as which indigenous figures can be attributed for the worldwide media attention these events have received.

The Guatemalan Civil War

The Guatemalan Civil War was a 36 year-long armed conflict between Guatemala's military government and the local guerillas. Many attribute the start of the war to the USA since, in 1954, the CIA supported a coup led by Colonel Carlos Castillo to overthrow the democratically-elected president, Jacobo Arbenz. Castillo and his supporters along with the United States did not support Arbenz due to his policies benefiting farming and indigineous communities. 1

Once Castillo was in power, he reverted may of the Arbenz's policies, one of the most significant being the removal of voting rights for illiterate Guatemalans. After six years of the military being in power, guerillas began to counterattack the goverment, ensueing what would turn out to be a thirty-six year long civil war. Despite the numerous human rights violations, the United States continued to supply the Guatemalan military with training and weapons for the most part of the war. 2

In 1982, General Efrain Rios Montt came into power and put into place a variety of dictatorial practices including the annullment of the constitution, Congress, and political parties. His reign marks one of the bloodiest periods of the civil war where Montt was determined to seize complete control and absolutely erradicate all guerilla efforts. 3

It wasn't until 1994, under the presidency of Ramiro De Leon Carpio, that peace negotiations started to occur. Finally, on December of 1996, the peace accords were signed between President Álvaro Arzu and the rebel groups. Despite the war being over on paper, the government has never fully gone back to a completely non-violent way of ruling. Intimidation tactics used on civilians are still a common practice and organized crime has become a major problem with little to no accountability. 4

The war has been known for being one of the most gruesome conflicts in Latin American history with almost 200,000 deaths and thousands more which were wounded, tortured, starved, and raped. Many of the people who were in power during the civil war have been found guilty of crimes against humanity for the massive genocide that took place along with the many human rights violations committed by the military. A U.N. report from 1999, states that 83% of the people killed were Maya with 93% of the crimes being attributed to the military government. 5

*October 1, 1982; Photo by Robert Nickelsberg; Guatemalan Military Soldiers are holding up a banner made by guerrilla groups. *

Rigoberta Menchú

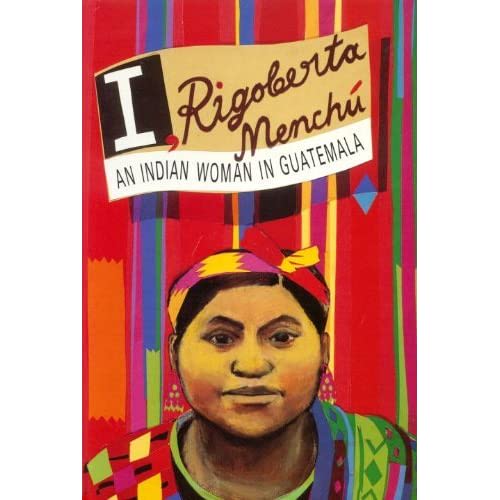

Rigoberta Menchú Tum is probable one of the most recognized indigenous female figures of our time. She is a Quiché Maya woman and was born on January 9, 1959 to a relatively poor Maya family in Guatemala. Her father was heavily involved in human rights activism and from a young age she was involved in a local women’s rights activist movement.1 Menchú grew up in what people consider to be one of Guatemala’s most violent periods after the Spanish Invasion. In 1954, five years before Menchú was born, Guatemala entered what would be 36 years of constant genocide and persecution of the country’s indigenous people. Menchú lived through many of the horrors that were shared between many of the Guatemalans who grew up in this era. By the time Menchú was around 20 years old, both her father and brother had been kidnapped, tortured, and eventually killed by the Guatemalan government. By the time she was 21, her mother had also been arrested, raped and murdered by military soldiers.2 The extreme amount of death and injustices suffered at the hands of the government prompted Menchú to engage in different demonstrations against the oppressive government and try to educate other Maya people about the resistance movement. This eventually culminated in her self-exile to Mexico in 1981 where she sought asylum from the growing threat against her in Guatemala. It was during this time that Menchú met Elisabeth Burgos Debray whom, after a week of interviews, helped Menchú compile an autobiography detailing her experience as a Maya woman who grew up and suffered first-hand the atrocities of the Guatemalan Civil War. The book was published in 1983 titled as Me llamo Rigoberta Menchú y así me nació la conciencia or as it’s more commonly known English translation, I, Rigoberta Menchú (1984).3 The book quickly garnered international recognition and for the first time, world-wide attention was being given to the usually discriminated Maya people of Guatemala, especially the Maya women. Menchú’s narrative broke the usual romantic narrative that is placed on Maya women and spoke to their struggles in gaining equality in comparison to ladinos in Guatemala.4 In 1992, she became the first indigenous woman to receive a Nobel Peace Prize, recognizing her unending battle for indigenous rights and Maya women rights in Guatemala.

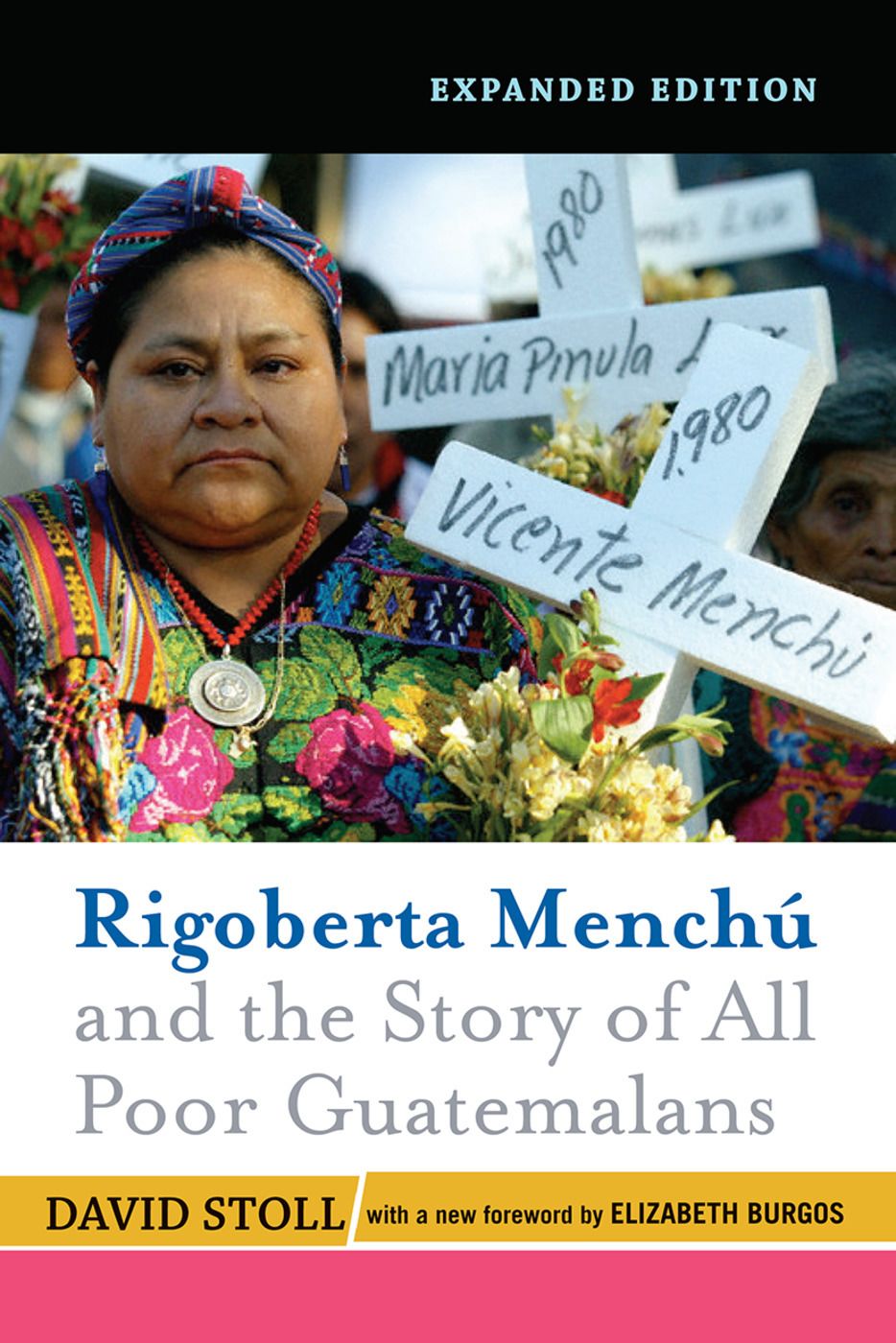

However, when a person shares their lives and experiences so publicly, it opens them up to public scrutiny and inherently invites others to give their own opinion about their lives and decisions. In Rigoberta Menchú’s case, this public opposer was the American anthropologist, David Stoll who in 1999 wrote a response and critic to Menchú’s autobiography called Rigoberta Menchú and the Story of All Poor Guatemalans. In his book, Stoll tries to create doubt around Menchú’s credibility by questioning the accuracy of her accounts. It is important to point out that to many people, such as Victoria Sanford and myself, it is extremely frustrating to see a white, foreign man try to discredit one of the only female Maya voices that has ever gained enough recognition to proactively speak about the harsh realities faced by indigenous communities as a whole. Especially when their book is filled with inaccuracies and misinterpretations that have then been passed on by big news outlets such as The New York Times.5 In his work, Stoll spins a narrative where more blame is placed on the guerillas and victims of the military’s war crimes. As Sanford explains in her article, Stoll acknowledges that the government enacted violence against its people but refuses to present it with the severity and accountability that has already been determined by national organizations such as the CEH which determined that the crimes carried out by the government were in fact genocidal attempts against the Maya.6 Another erroneous fact that is propelled by Stoll’s book is the idea that the United States had no relationship nor involvement in the Guatemalan Civil War. For this argument, one has to not look further than the CIA online library where they have a collection of around 5,120 documents which detail the ways in which the United States was involved in the military coup of 1954 and the reasoning behind the involvement. (Check out the CIA documents here.) Overall, Stoll’s work was completely unfair and inaccurate in the claims he made against Menchú’s book and it’s disappointing that his retelling of events which he took no place in gained so much media attention. Nowadays, Rigoberta Menchú continues her fight for the recognition of Maya rights, especially Maya women. In the last 15 years, she has run for president twice and founded the Rigoberta Menchú Tum foundation which is dedicated to helping victims of the Civil War. She hopes to continue opening doors for Maya women to integrate themselves more into politics and positions of power in order to bring significant change to their communities.

Rigoberta Menchú Tum; Image from https://nobelwomensinitiative.org/laureate/rigoberta-menchu-tum/

Rigoberta Menchú Tum; Image from https://nobelwomensinitiative.org/laureate/rigoberta-menchu-tum/

I, Rigoberta Menchú by Rigoberta Menchú; Image from https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/233292.I_Rigoberta_Mench_

I, Rigoberta Menchú by Rigoberta Menchú; Image from https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/233292.I_Rigoberta_Mench_

David Stoll; Image from http://www.middlebury.edu/academics/es/faculty/node/25831

David Stoll; Image from http://www.middlebury.edu/academics/es/faculty/node/25831

Rigoberta Menchú and the Story of All Poor Guatemalans by David Stoll; Image from https://www.routledge.com/Rigoberta-Menchu-and-the-Story-of-All-Poor-Guatemalans-New-Foreword-by/Stoll/p/book/9780813343969

Rigoberta Menchú and the Story of All Poor Guatemalans by David Stoll; Image from https://www.routledge.com/Rigoberta-Menchu-and-the-Story-of-All-Poor-Guatemalans-New-Foreword-by/Stoll/p/book/9780813343969

Check out Rigoberta Menchú's talk on what she wishes to achieve through her activism.

Check out Rigoberta Menchú's talk on what she wishes to achieve through her activism.

Maya women in steps in front of the Supreme Court before the start of their rape trial; Image by Jeff Abbott

Maya women in steps in front of the Supreme Court before the start of their rape trial; Image by Jeff Abbott

Maya women on their first day of trial against two military soldiers they are accusing of sexual violance during the Civil War; Image by Moises Castillo

Maya women on their first day of trial against two military soldiers they are accusing of sexual violance during the Civil War; Image by Moises Castillo

Maya women inn front of the courthouse in Guatemala https://www.pri.org/stories/2016-12-12/interpreter-helping-get-justice-indigenous-women-raped-and-tortured-guatemala-s of the last day of their trial; Image from

Maya women inn front of the courthouse in Guatemala https://www.pri.org/stories/2016-12-12/interpreter-helping-get-justice-indigenous-women-raped-and-tortured-guatemala-s of the last day of their trial; Image from

Rape as a Tool of War

In 1999, the CEH (Commission for Historical Clarification) revealed that out of the 200,000 deaths in the Civil War 25% were women.1 However, that only makes up a small percentage of the women who suffered all kinds of atrocities at the hands of mainly the Guatemalan military but also the guerillas. Like in many other armed conflicts, sexual violence was one of the main tools used by the military regime in order to control and further destroy the Maya communities and villages. As Amandine Fulchiron mentions in her article, “The systematic sexual assault that was committed against Maya women on large scale during the war was one of the most important silences in Guatemalan history.”2 Their stories of rape and assault have been left widely untouched at a legal and national level. Typically, when people discuss the matter of large-scale rape in armed conflicts, it is considered a common occurrence. It has become such a normalized behavior that when women try to bring attention to it, it is often dismissed or not given as much attention as other “war crimes” that might have been committed. This is also largely due to the fact that in criminal court cases, it is very hard to successfully accuse someone of rape. However, despite all of this, sexual violence during the Guatemalan Civil War is most certainly a crime against humanity. In its study of the events of the civil war, the CEH declared that rape was indeed used as a war strategy. It’s used as method to intimidate and subordinate the enemy, especially since through the women you manage to break the resilience and moral of the entire community.3 These acts were usually committed in public in front of the entire village or your entire family. In Fulchiron’s study, women recount how they would be raped in front of their husbands and children or daughters raped in front of their fathers. The military was ultimately sending a message of power and control. They were making sure that everyone knew they could do as they please with whoever they wished.

The survivors of sexual violence during the civil war, faced large amounts of judgement and scrutiny from their families and communities. Due to the modern Maya’s strict patriarchal society, the perspective of many of these communities towards the victims was one of blame. The narrative that started to gain momentum was that of the women willingly giving themselves to the soldiers and selling out their bodies. Many of these victims agreed in the aspect that they were seen as used or not worthy of respect. Many women had to leave their villages in order to try and move forward with their lives. Ultimately, the effects these crimes of sexual violence have broken apart many Maya communities and families, which, in a way, is what the oppressive military regime was striving for. There was also an increase in abortions and filicides in the years after the wars due to the hate people would have towards the children of rape.4 The psychological impacts these events had on Maya women is one that they will have to deal with for the rest of their lives and with the lack of support from families or communities it is an even harder process of recovery. In the last 6 years several victims have tried to take some of their rapists to trial, but these rarely end in their favor.

Although Classic Maya women and modern maya women lived centuries apart and in completely different societal contexts, we can see that, through the stories shared today, the presence of Maya women is one that has been constantly tried to be supressed. Hundreds of years have passed, and it seems that Maya women have still not been able to take a hold of their stories and share their realities with the world. They’re in a continuous struggle to have any sort of agency in the decisions made regarding their livelihoods and wellbeing. Hopefully, as we move forward this dynamic between Maya and non-Maya Guatemalans changes.

Around 3/4 of the women in Guatemala are a part of Mayan communities. This brief documentary explains some of the struggles faced by these women who were victims of sexual violence during the civil war.

Around 3/4 of the women in Guatemala are a part of Mayan communities. This brief documentary explains some of the struggles faced by these women who were victims of sexual violence during the civil war.

Final Remarks

When talking about experiences in relation to gender, it is not possible to make a generalized statement that can embody the realities of all women, no matter the time period. We can only evaluate and interpret different circumstances and how each situation has affected certain groups of women. Throughout this page we’ve seen the different realities suffered by Maya women across the centuries. At the beginning, it might have been easier to declare one reality better than the other. However, this mindset would not be fair for neither ancient nor modern Maya women.

The role of Maya women has been one of great importance but massively unappreciated by their communities. It is true that we have had amazing examples of Maya women as figures of power like the Lady of Tikal or Rigoberta Menchú. However, there should be more. It should be completely unacceptable that, in a country where more than half of the population is of Maya descent, the first time an indigenous person ran for presidency was in 2007. I hope that through this page, people can reflect on how their own silence and disinterest in such matters contributes to the hardships these women face.